Inside Turtle Bay Gardens Where Katharine Hepburn Once Lived

This 1920 image is by Frances Benjamin Johnston, one of the first female photojournalists.

Photo: Heritage Art/Heritage Images/Getty Images

Wedged between the cheerless skyscrapers of Third Avenue and an uncharming stretch of Second, just blocks north of the bro bars of Murray Hill, is a row of nine townhouses. They have flat façades and modest entrances a step down from the street beside lines of trash bins. One block south, on 48th Street, is another row of similarly unassuming design. Anyone passing by might not guess that these houses are connected and centered on a shady private garden. Or that they have acted as a sort of year-round summer retreat for generations of actors and writers — a place where E.B. White could get writing done, where Robert Gottlieb could edit from bed, and where Bob Dylan could avoid prying eyes, except for those of his next-door neighbor, Katharine Hepburn.

Turtle Bay’s heiress-developer Charlotte Hunnewell Martin.

Photo: Gift of the Estate of Peter Marié

Together, these 19 townhouses make up Turtle Bay Gardens, created around 1920 by a developer who renovated the 1860s-era homes all at once. Each has its own small private space, with low walls, that looks onto an unusually beautiful shared garden. That developer was an heiress named Charlotte Hunnewell Sorchan. The press at the time reported the idea first came up at a tea at the Ritz-Carlton shortly after World War I, where her friends had apparently been complaining they couldn’t find good affordable housing; the war had put a stop to new construction, and prices were out of control. She had the funds for a solution. After some hunting, she came across two rows of brownstones in a “quarter that was then considered too far east,” as she later wrote. Working families, wedged there between elevated-train lines, had used their yards to vent kitchen smoke, hang laundry, and store garbage. She and her friends saw potential, with press reports saying that they were inspired to create something like “a little villa in ancient Italy.”

Over the next few years, Hunnewell Martin — she remarried in 1921 — and a pair of Paris-educated architects renovated the houses with the idea of aligning the living areas to face the garden and moving the smoky kitchens toward the street. The homes at each corner looked out onto the yard from loggias capped with open terraces. The architects deliberately attempted to differentiate each house: Some had terraces, others would have columns or frescoes or bas-relief figures, and the gates leading to the garden had unique constellations of wrought iron.

The Gates to the Garden: Each townhouse has its own entrance to the garden. And each has its own distinct personality. Photo: Frankie Alduino.

The Gates to the Garden: Each townhouse has its own entrance to the garden. And each has its own distinct personality. Photo: Frankie Alduino.

Hunnewell Martin seemed to seek out buyers who both shared her vision and might be good ambassadors for the project. She sold some of the homes at a loss, selecting for prominent New Yorkers including a judge, a former congressman, lawyers, and the founder of the Chapin School. There were also a handful of writers and editors who may have signed up to be near the center of publishing in midtown, like a book reviewer for The New Republic, the first winner of the Pulitzer Prize for fiction, and soon after Maxwell Perkins, who could walk to work at Scribner, then host the writers he was editing, such as Thomas Wolfe, who was once spotted climbing into the house through a terrace window. (The Perkins legacy to the Gardens included a poodle whose puppies were given away to neighbors.)

Hunnewell Martin’s recruits leaned left. Who else would agree to live in what was sort of a socialist experiment? Owners had to agree to a set of rules about how they would use the garden, which were enforced by Gillet Lefferts, a lawyer from one of Brooklyn’s oldest landowning families, who raised his children here — maybe the only spot in Manhattan where they could both share a sandbox with the prominent Platt family and keep a pet skunk that hibernated outside.

The staff of The New Yorker started arriving in 1935 when the magazine’s office opened on 44th Street. That year, the fiction editor Katharine Angell and her husband, E.B. White, rented 245 East 48th Street. An executive at the magazine, Stephen Botsford, moved in down the street, and his brother, Gardner, a prominent editor, would buy across the Gardens. By the time J.P. McEvoy, a playwright, humorist, and contributor to Reader’s Digest, came in 1948, the place had developed a reputation as a creative enclave. “It wasn’t full of rich people,” said Peggy McEvoy, his daughter. “It was full of like-minded people.” There were parties in the garden, informal dinners, playdates and sleepovers, and a roving Christmas party once fueled by bottles of Champagne stuck in the snow. At the center of the action was a fountain, situated beside a gnarled willow tree that was there before Hunnewell Martin even arrived. In 1949, E. B. White turned that tree into a symbol of the city’s resilience, ending on its image in his most famous essay, “Here Is New York.” His third Turtle Bay Gardens rental — a duplex in No. 229 — would have faced not just the tree but the back of Hunnewell Martin’s townhouse; by 1952, she was in her 80s and was speculated to be the inspiration for that year’s Charlotte’s Web. (The posh-sounding spider does expend the last of her energies dreaming up a more livable future for her children.)

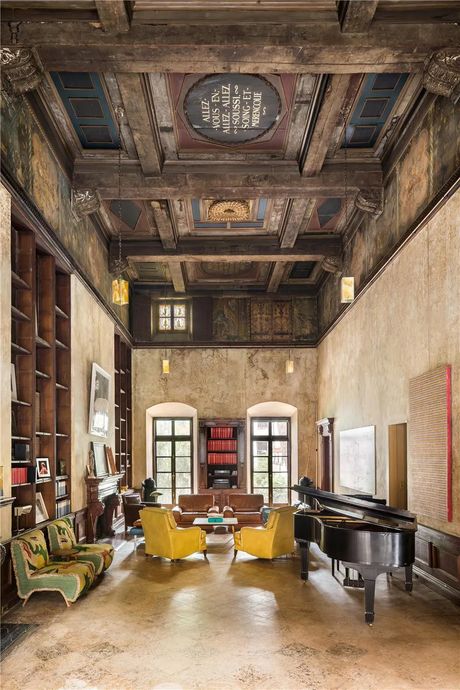

The enormous loggia shaded from the garden at Charlotte Hunnewell Martin’s house, photographed in 1920.

Photo: Heritage Art/Heritage Images/Getty Images

White and other influential writer-neighbors had a hand in saving Hunnewell Martin’s project from destruction when the area suddenly found itself a less than ten-minute walk from the new center of global power: the United Nations. Owners on the Gardens happily helped arrange the sale of the former Lefferts home at the eastern end of 48th Street to a group of Quakers, which used it for diplomatic work. But in 1947, developer William Zeckendorf proposed razing Turtle Bay Gardens to build a concourse to the U.N. — an idea that was scuttled after White and his neighbor Dorothy Thompson, the anti-fascist columnist, defended their homes in letters to the New York Times, the New York Tribune, and The New Yorker. While the U.N. rose, other developments began to grow on Second and Third Avenues as the elevated-train lines came down, making the area more attractive for apartments and skyscrapers. Katharine Hepburn had been on the Gardens since the early 1930s, and decades later, she told the screenwriting couple who had first cast her with Spencer Tracy — Garson Kanin and Ruth Gordon — that “property values are sure to increase” there. (She personally suggested her neighbors to sell to them, and they moved there in 1951.) It proved true: When Stephen Sondheim bought on the other side of Hepburn nine years later, in 1960, the area was still seen as an investment. (He scooped up Perkins’s former home, renting a triplex upstairs to the singer Anita Ellis and taking a smaller unit for himself.)

Sondheim quickly became a chatty and active member of the garden committee, which met semi-annually in the living rooms of members and considered such problems as how to force owners to clean up their dog poop — in the 1940s, a survey turned up an astonishing 17 dogs had the run of the garden — and whether it was appropriate to regulate children. It was not always easy to get everyone on the same page. Peggy McEvoy, who sat on the committee, remembered a time when kids were “breaking windows with baseball bats” and kindhearted Gordon came to their defense, saying, “Oh, I think it’s delightful listening to those cute little kids.”

As the Kanin-Gordons spent more time away from New York, they rented to a stream of Hollywood types: Director Mike Nichols installed an intercom in their home, Mary Tyler Moore turned the top floor into a dance studio, and Franco Zeffirelli used the study to plan operas. The author Kati Marton rented the house in 1983 when her husband, Peter Jennings, got the top anchor job at ABC News. “It was like being in a very strange Fellini film,” said Marton, who remembered getting baskets of sweet onions from the Kanin-Gordons as a jokey move-in gift. Kanin eventually sold to Bob Dylan, who put a couple who worked for him on the deed to avert the press. “Bob was very private,” remembered Dylan’s former fix-it man, Michael Leshner.

Celebrities looking for privacy didn’t always make the most sociable neighbors. When the actress Maria Tucci and her husband, Robert Gottlieb, moved in, in 1973, Tucci felt isolated. Things improved in the mid-1970s, when she met Janet Malcolm — another working mother married to an editor. The two quickly bonded, and Malcolm’s daughter, Anne, basically moved into the Tucci-Gottlieb household, which had a reputation for sheltering stragglers. The actress Kate Reid lived for a while in the library on a pullout sofa, Nora Ephron moved in upstairs with her two sons during her divorce, and Doris Lessing and Edna O’Brien would stay there whenever they were in town.

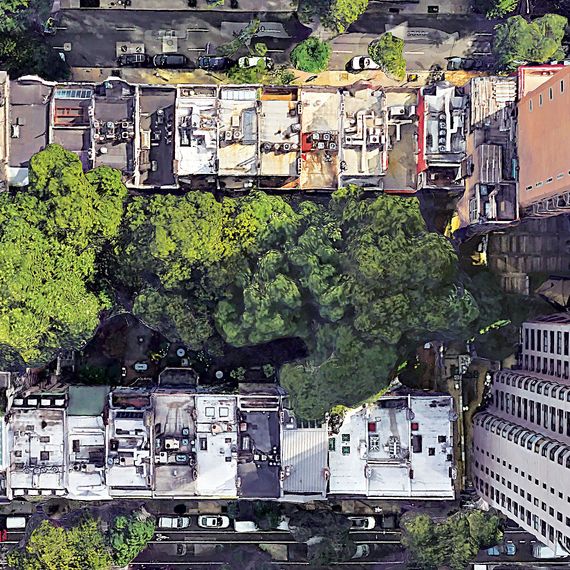

A bird’s-eye view of the Turtle Bay Gardens townhouses.

Photo: Google Earth

The Botsford-Malcolms put their house up for sale in the late ’80s, but it sat on the market. Updating a Turtle Bay townhome built without central air and elevators could be wildly expensive, as could paying taxes on it, and families with that kind of money didn’t seem interested in this slice of midtown by way of Murray Hill, which was being shadowed by skyscrapers. Instead, the Botsford-Malcolm sale turned the house into a consulate for a newly independent Ukraine — a place where officials could meet, then easily pop over to the U.N. Ukraine wasn’t the last nation to show up; a decade later, South Africa bought the house next to Hunnewell Martin’s. The new diplomatic owners chilled the mood, however. While the consular staffs could be seen using the buildings — and in 2014, during Ukraine’s Maidan Revolution, the consulate was astir with late-night activity — they weren’t taking on creative landscaping projects or swilling drinks at committee meetings. Other new owners tended not to come with children. “They’re major investors, and there are layers of management,” said Jesus Rodriguez, a contractor who worked on many of the homes on the Gardens over the past 40 years, becoming friendly enough with some owners to be repaid in theater tickets (Sondheim) or stays at Paris apartments (Gottlieb).

During the pandemic, the once chatty garden-committee meetings migrated to Zoom, and the Gardens was so quiet that a therapist let a meditation teacher use her living room and lead students on walks through the trees. Hunnewell Martin’s former mansion, meanwhile, has become a sort of perpetual construction site since Olivier Sarkozy bought and staged an elaborate wedding to Mary-Kate Olsen there in 2015, began a renovation, and sold amid their divorce. Rodriguez had a look inside around that time and found most of the house was “completely destroyed,” he said. “It’s like a shell.”

Sondheim left for Connecticut in the pandemic and died the next year. His townhouse, with its Gothic arches and stained glass, has since sold for $7 million to a family craving outdoor space and the freedom to adopt a dog (though they chose a dachshund, not a poodle). The new owner, Pasha Sarraf, works in health care but makes use of shelves that Sondheim sized to the width of cassette tapes. “Everything was carefully constructed,” Sarraf observed, “like a verse in his Broadway plays.” The Hunnewell Martin–Sarkozy–Olsen townhouse recently sold to the owner of an artisanal-tile empire, Deborah Osburn, who delved into research on Hunnewell Martin to pull off an informed restoration. Other houses on the Gardens have been put up for sale, too: 241 East 48th Street was listed at $13.95 million — a price that probably would have been unimaginable to its longtime former owner, magazine editor and literary agent Julian S. Bach. (And a price that may not be achievable: Next door, 239 East 48th Street is asking $6.75 million and has been on the market for more than a year.) In May, Hepburn’s former home was put up for sale for $7.2 million, listed by the property group that bought it after her death in 2003. And Gottlieb’s home may soon have a FOR SALE sign. The editor died at 92 in June 2023 as the sole holdover from a century of editors and writers who wanted to live near the center of publishing. “Gottlieb was one of the last real artists still living here,” said Peggy McEvoy.

Photo: Frankie Alduino

MOVED IN 1948

Retired public-health worker

I only ever lived here full time in fifth grade and ninth grade. It was really more like our winter house; we were living in Cuba. But I remember coming here after I’d come home from school in Switzerland. I took over the house full time when I was 36, when my mother died. At that time, I was on the executive committee with Stephen Sondheim. One of our neighbors once said, “You guys run this garden with a whim of iron.” At the meetings, we had wine and very good cheese. And Scotch-and-soda. This is a hard-drinking group!

Photo: Frankie Alduino

MOVED IN 2007

Nonprofit executive

I lived here growing up and moved back in to be with my mom after I got married and got pregnant. When I was a kid, we were all very close. We hosted three or four Thanksgivings with the artist David Deutsch. We’d set up big, long tables. We had this dog, and our neighbors Margo and Jeremy had a dog and they had puppies together. Our dog was a Pekingese, and their dog was a purebred. It created really funny-looking puppies — born under my bed. The garden used to be very, very pretty. And it was a magical place to play.

Photo: Frankie Alduino

MOVED IN 2021

Quaker House director

The Quakers purchased this house in 1953. It was a very strategic decision, made in an era when New York real estate was not as expensive as it is today and only possible because of contributions from various donors. I think the largest one was from the Rockefeller brothers. The director lives here part time — which means I live here part time. It’s strange to have your work be the place where you wake up at 6:30 in the morning. You’re very conscious of cleaning up after yourself and stuff like that. The space is basically the same as it was when I first saw it in 1998. Quakerism is a very decentralized religion, very flat, not hierarchical at all. The act of being like, “We need to change the painting in the living room” — I mean, something as simple as that was the topic of many emails and meetings. Everybody had to agree.

Photo: Frankie Alduino

MOVED IN 2014

Fashion entrepreneur

I was living in London. My husband came and saw the house with my friend. I’d always wanted to live in a house, not an apartment building. You always worry, We’re raising our child in an urban environment. Are we doing the right thing? When we moved in, it was a snowy evening. There was a little girl who lived in the Ukraine Consulate with her family — I guess he was the consul general. She was out playing in the snow at ten at night with her dad, and my son was like, “Can I go play in the snow?” I’m like, “Of course you can’t go play in the snow. We’re in New York City.” And then I was like, “Wait, of course you can go play in the snow. You could play in the garden.”

Photo: Frankie Alduino

MOVED IN 1973

Actress

My husband Bob’s closest friend for many years was Richard Howard. One of his more steady boyfriends was Sanford Friedman. His brother was B. H. Friedman — he was tall, arrogant, and not a very nice guy. We went to the ballet and Bob bumps into B.H., who lived on the Gardens. Bob said something like “Maybe we’ll buy your house.” I didn’t want to buy his house. I didn’t like it from the moment I walked in. It was just too grand. There were lots of major paintings. None of them interested me much. But Bob said, “We’ll buy it.” So we did. And we sloppied it up.

Photo: Frankie Alduino

MOVED IN 2021

Lawyer and photo editor

A few years before we moved in, a friend of mine who lived here was offering a meditation class in the garden; she’s a therapist, and she was doing it with a meditation teacher. I came and I was like, What is this place? On Facebook in the fall of 2020, I saw she was building a house upstate. I messaged her: “What are you doing with that apartment?” She said she was giving it up. We owned a condo in Fidi at the time — we had a roof-deck, a valet. But we rushed here the next morning and took it. We were so worried we were going to lose it. When people come visit us, I like to watch their faces. They’re like, Oh my God.

Oliver Sarkozy’s former mansion (left) and Steven Sondheim’s former home. Photo: Douglas Elliman (Sarkozy); Compass (Sondheim).

Oliver Sarkozy’s former mansion (left) and Steven Sondheim’s former home. Photo: Douglas Elliman (Sarkozy); Compass (Sondheim).

Abel Detmold managed repairs, took in packages, found renters, and kept keys for homes on the Gardens until her death in 1964, gradually leaving the duties to her son Peter, who took over the job and expanded it. Unlike his mother, Peter didn’t commute home to Queens but lived on the Gardens in a rental at 229 East 48th Street. He also became a civic leader, known for fighting to preserve historic buildings and opposing unruly businesses. In the 1960s, he recruited neighbors to help start the Turtle Bay Gazette, a local newsletter. On January 6, 1972, he left a Gazette meeting at 8 p.m. with two members. One walked him all the way to her building across 48th Street. He crossed the street to his apartment, and police said he was stabbed in the chest as he entered. A Village Voice article suggested he was targeted because he had opposed a club with mob connections. An ex-girlfriend said he had been so worried about his safety he had warned her that if anything ever happened to him, she should “look for the corporate people who are trying to tear the houses down.” This came as a complete bombshell to the residents, said Peggy McEvoy, who lived on the block and had seen him earlier that day. “People were shocked. Nobody really knew what it was about.” Bess Detmold heard about the tragedy secondhand through her husband, Peter’s brother: “I know my husband, John, got the call and he went right into the city to tell his father so his father wouldn’t get a phone call. I think they always wondered just what had happened.”

In the late 1980s, a staff writer protested the magazine’s new hire for editor-in-chief. Both lived on the Gardens.

in the 1970s, The New Yorker’s editor-in-chief William Shawn considered who should replace him. He suggested that longtime editor Gardner Botsford, who owned a home on the Gardens, could take over. But Shawn didn’t step down as planned. In 1987, Si Newhouse ousted Shawn and hired Knopf editor Robert Gottlieb, who also lived on the Gardens. 153 staffers at the magazine — including Botsford’s wife, Janet Malcolm — signed a letter against Shawn’s deposition. The split seemed more awkward than it was, said Malcolm’s daughter, Anne. “The issues my parents had were with Newhouse and the defenestration of Shawn,” she said. The two families, who were very close, continued to eat dinner together regularly, with Botsford bringing his own martinis to the Gottlieb house, mixed to his liking in a sealed jam jar.

In 1985, the committee found itself dealing with a violent threat: a Balinese cat prone to fighting other cats. It was owned by the son of Peggy McEvoy, who received a stern letter from the Gardens caretaker, Therese Perry, whose similarly named cat, Chi Cha, was attacked. “I am not the only one on the garden that feels that Cous Cous is a very unfriendly and dangerous cat,” Perry wrote. “I do not intend to stand for it any longer.” McEvoy remembered Perry as a “witch” who would punish the cat by locking it in basements. But Janet Malcolm was sympathetic because her own cat had been attacked by Cous Cous, too, said her daughter. Malcolm played peacekeeper, suggesting that McEvoy pay for Chi Cha’s sutures and sending the committee a note that “feline peace” had been restored as the “bellicose Cous Cous is no longer to be seen in the garden.” “L’affaire des Chats is finished happily,” reported literary agent Julian S. Bach to the rest of the committee. But soon there was another animal-related problem. Signing a letter with the title “Chairman, the Committee for the Advancement of Sanitation among the Privileged,” Malcolm implored the residents of the Gardens to clean up, as “there are dog turds everywhere.”

Katharine Hepburn sweeping on the Gardens on New Year’s Day 1988.

Photo: John Bryson/Getty Images

The actress arrived in the early 1930s and became a constant, if difficult, presence, bringing her high standards to a community of oddballs. Her fights with noisy neighbors made the press during her lifetime, and people who still live on the Gardens remember the Hepburn era well.

Jones Harris, son of Ruth Gordon: “I remember how noisy Sondheim was when Hepburn had her opening night in Coco to face the next day. And suddenly, there was a lot of shouting and yelling and so forth and so on. I didn’t want to speak to him, but I called the police. They all knew her, of course.”

Sondheim: “I remember asking Hepburn why she didn’t just call me, but she claimed not to have my phone number. My guess is that she wanted to stand there in her bare feet, suffering for her art.”

Anne Malcolm, Janet Malcolm’s daughter: “Some friends of mine once came in and said, ‘Oh my God, we just got yelled at by Katharine Hepburn!’ That’s about as much as I ever encountered her. Every neighborhood has an older lady who doesn’t necessarily want young people making noise under her. I’m turning into that lady now.”

Michelle Doty: “She wasn’t warm and fuzzy.”

Peggy McEvoy: “The kids used to shovel her garden when it snowed for two bucks and get her signature. Then they’d try to sell it.”

Maria Tucci: “My Lizzie would run naked in the garden because she was 2 years old. Once, Hepburn said, ‘You let your child run naked in the garden?’ I said, ‘Well, I don’t know who I’m shocking.’”

The Gardens shares its name with the area, but it’s unclear where the name came from. Here, some lore.

1. A Misunderstanding

Mabel Detmold, an early caretaker on the Gardens, wrote that “Turtle” might have been a mishearing, having seen early maps that refer to the area as “Dewtell,” which is possibly a misspelling of Deutal, a 17th-century Dutch word for a dowel.

2. Actual Reptiles

Explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano described bounties of “terrapin” in Manhattan in 1524, and a 1765 letter sought recruits from “Tortoise Bay.”

3. Socialists

At least one person — a critic of the incrementalist socialist movement Fabianism — thought that a turtle image in the garden meant the space might have been a Fabian project.

Photo: Frankie Alduino

The arborist William Bryant Logan likes to say he ran his business like a doctor’s office, making regular house calls to patients from the Metropolitan Museum of Art down to Madison Square Park. Around 2003, he got a call about a new case: A member of the Turtle Bay Gardens Committee thought an expert’s help was needed with the trees — in particular, E. B. White’s willow. When Logan found it, it was falling apart, “getting more and more rotten,” according to Peggy McEvoy. Logan pruned nearby trees to bring in more sun, added humic and fulvic acids to the soil, and kept the willow stable by rigging it with cables. Five years after his first intervention, the bark started to crack, revealing a trunk that was, per Logan, “thinner than crockery.” Eventually, the residents voted to take it down (with one dissenting vote). Logan put most of the tree into a chipper, but a few branches came back with him to Red Hook, where he keeps his equipment on a lot. The next spring, staffers doing an inventory of his company’s saplings noted a willow tree — a genetic twin of White’s, since willows grow from their own cut stems. When it’s pruned, Logan saves the cuttings, which he gives away to anyone who asks — though he has another way of propagating them. “Somewhat surreptitiously, we plant them,” he said. Though the original willow is gone, Logan still tends to the other trees of Turtle Bay — visiting once or twice a year to make sure everything else is in order.

Photo: Douglas Elliman

Initially the residence of art dealer Walter Ehrich, it became the longtime home of literary agent Julian S. Bach. Typical for the Gardens, there are four bedrooms and five and a half bathrooms, but the $13.95 million cost reflects some pricey upgrades: an elevator, a reworked kitchen, a high-ceilinged sunroom, and an enormous mirrored walk-in closet.

Photo: Douglas Elliman

Charlotte Hunnewell martin originally sold the home to two professional women — an attorney and a Brearley teacher — who divided it in two. One apartment was later rented briefly, during World War II, to E. B. White. This home is slightly less renovated than the other (which is possibly why the price dropped by $245,000 to a more reasonable $6.75 million earlier this year).

See All

Source link