NYC Is Ending Its Decrepit Streetery Era

Photo: James Andrews/Shutterstock

The signs of COVID City are fading. Tattered yellow decals on subway platforms sport a pair of footprints and the admonition to “keep a safe social distance from others,” a phrase that will grow more mysterious with each passing year. Some stores never bothered to take down signs requiring masks for entry. The last redoubts of pandemic architecture, the restaurant sheds made of plywood and two-by-fours that kept hardened New York diners eating out through all but the most frigid weeks, are finally coming down. In their place we’re getting a much smaller flotilla of lightweight canopied cafés that meet new city regulations. The Wild West era of outdoor dining is dead; long live the domesticated version.

Dynamic cities keep tinkering with new ways of making themselves livable. Experimentation is generally a slow and fitful process. (Composting, not exactly a revolutionary concept, has been inching across the boroughs for years.) But the pandemic supercharged cities’ improvisational skills. As it hurtled along, tossing aside normalcy from every aspect of human behavior, officials scrambled to make their bureaucracies adapt. Colored tape, traffic cones, and cans of spray paint became the essential materials of sped-up city planning. Suddenly we were all living in a jury-rigged metropolis. Those adaptations could be comforting: Every Thursday afternoon for months, my wife and I toted a contraband six-pack and a couple of camp chairs to the park to meet two other couples. We arranged ourselves in an equilateral triangle with double points and ten-foot sides, shouting across the divide. But a DIY city can also be dangerous. Around that time, a flimsy sawhorse blocked off an avenue in my neighborhood, turning it into an open street; when the driver of a speeding box truck crashed right through it, I dodged a quick and violent death. In the weeks that followed my near miss, I saw a dozen other vehicles ram the same shattered sawhorse, which nobody ever replaced.

As it became obvious that pedestrians needed room to spread out — to breathe, move, and socialize — I hoped that some of those experiments would get absorbed into the city’s operating system. Once we passed the stage where we needed to keep each other at pole’s length, we wouldn’t just turn that turf back over to vehicles, would we? Having acquired the habit of fresh-air dining, surely we wouldn’t willingly get herded back into cramped and noisy quarters. Congestion pricing would whittle down traffic, making more acreage available for everything that isn’t traffic. Wouldn’t it?

The answers have been contradictory and often disappointing. Traffic returned in a cloud of non-glory, clogging the streets even more ferociously than it did before the pandemic. Even so, congestion pricing never got a chance. The Adams administration has built a fraction of the bike lanes it promised. Drivers are eyeing the parking spots that streeteries are about to relinquish en masse. And yet, the four years since the six-feet-apart admonitions emerged have left me guardedly (perhaps naïvely) optimistic. So has the new phase in outdoor dining.

Dining sheds lining the street in Little Italy.

Photo: Jimin Kim/SOPA Images/Shutterstock

The provisional greenhouse structures of the early pandemic allowed diners to eat outside in winter temperatures.

Photo: Lindsey Nicholson/Universal Images Group/Getty/Education Images

During the pandemic, thousands of restaurants all over the city expanded onto sidewalks and roadways under the city’s emergency program, all for free and with virtually no supervision. The anarchy was deliberate and crucial. At a time when many hesitated to leave their apartments, while squadrons of deliveristas braved snowstorms and viruses to bring them sustenance, the restaurant business depended on that economic respirator. The streets needed a shot of vibrancy, and outdoor turf offset the loss of off-limits dining rooms. Then indoor dining crept back, and some establishments effectively doubled their footprint by banging together outbuildings that could be heated, lit, and sheltered from foul weather. Just as the global food chain allows us to eat eggplant in winter and grapes in the spring, pandemic rules made it possible to picnic in polar conditions. Some places turned their sheds into ornate pavilions, others eventually abandoned them to squatters and rats. A reset was coming.

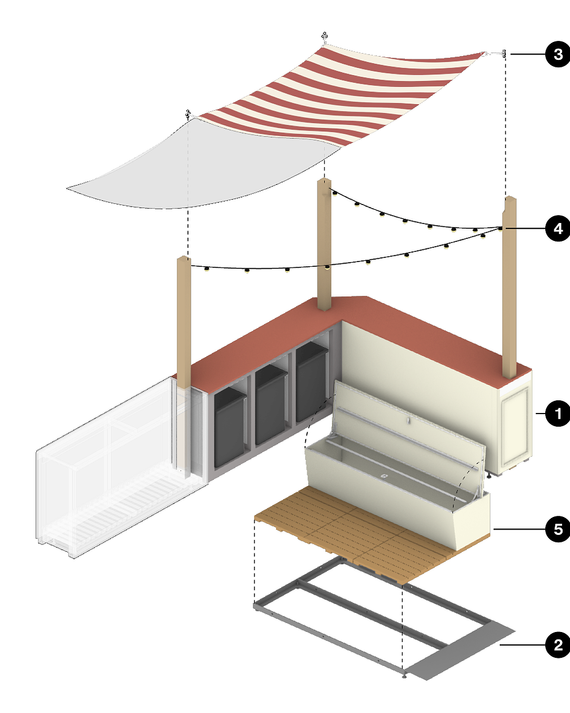

And so a team led by the mayor’s chief public space officer, Ya-Ting Liu, spent months turning a scramble into a system. Now, restaurants can still colonize sidewalks and roadways, but they must abide by a menu of commonsense restrictions. Sidewalk cafés and roadway structures require separate applications and fees; eligible restaurants can submit either or both. The city recruited two architecture firms, SITU Studio and WXY, to develop prototypes and come up with design principles, and the results are elegant and pragmatic: Streeteries that occupy parking spaces must now be sturdy, lightweight, and modular, protected by water-filled barriers (no more sand or earth ballast). Floors must be laid down in sections so that they can be quickly taken up and the creatures dwelling beneath them can be evicted. Roofs must be the kind that flap. Most important, the whole apparatus gets dismantled and stored after Thanksgiving, to reappear in April — ending arctic dinners under erratic heat lamps that many romanticize but few still choose. The administration’s outdoor dining website has links to designers, suppliers, and storage companies that can smooth the process. The city will finally lose that shantytown look of rotting shacks.

From left: New prototypes by WXY architecture and SITU Studio demonstrate the requirements about how the dining shed must meet the street and the curb Photo: SITUPhoto: SITU

From top: New prototypes by WXY architecture and SITU Studio demonstrate the requirements about how the dining shed must meet the street and the curb …

From top: New prototypes by WXY architecture and SITU Studio demonstrate the requirements about how the dining shed must meet the street and the curb Photo: SITUPhoto: SITU

Fabricating a dining shed that can be dissembled and put together, based on the new city guidelines, designed by WXY architecture + urban design and SITU Studio in partnership with many city agencies.

Photo: SITU

There’s a tradeoff, of course: The process and the seasonality have proven too great a burden for a lot of business owners. Only 2,661 restaurants have applied for the permits — a fraction of the number that operated at the peak of the temporary arrangement. Meanwhile, cars are exercising their right of return, backing into the spaces that the old sheds surrender—happier news for diehard drivers than for everybody else. Still, there’s a word for the advent of fees, permits, and bureaucracy: It’s called order. That’s something the city badly needs, especially now, when the forces of entropy seem ready to exploit any chink and crevice. With subway crime stubbornly refusing to sink—and ridership refusing to rise—back to pre-COVID levels, with rats on a rampage, homelessness endemic, migrants being housed in massive tents, food delivery workers zipping around on lightless e-bikes propelled by incendiary batteries, and drivers picking off pedestrians by the dozen, the city is constantly fighting off the encroachments of chaos. In the last couple of years New Yorkers have mostly come out of their shells and reclaimed the streets, only to encounter the infuriating sort of pinch point where a streetside café, scaffolding, garbage bins, and a resting herd of delivery bikes all converge, making the sidewalk impassable. New needs demand new rules.

The temporary outdoor dining scene nurtured Paris envy. Why can’t we have all those sprawling, boulevard cafés, or the corner joints where you can pause for a demi or an express and have it served en terasse? But Paris is hardly a sidewalk free-for-all. The rules governing enclosed and seasonal terasses are detailed and extensive, making New York’s new regime seem laissez-faire by comparison. For instance: Enclosed porches must be harmonious with the surrounding architecture, and café tables may not obstruct the passage of municipal sidewalk-cleaning machines—an utterly foreign concept in New York. The flood of clauses and prohibitions (recently fortified by new post-pandemic regulations) hasn’t prevented Paris from being Paris, and it shouldn’t scare New Yorkers back indoors. Our café scene will probably grow over time, if not to French dimensions, then enough so that those who now complain that it’s dying may eventually start complaining that it’s out of control.

A prototype of a dining shed that follows the new DOT rules, by WXY architecture + urban design and SITU Studio.

Photo: SITU

A collaboration to show the new city guidelines by WXY architecture and SITU Studio.

Photo: SITU

Even so, the program’s success will depend less on rules and procedures than how they are administered. The Department of Transportation tried to keep the process relatively frictionless, but the city council introduced a potential booby trap. The legislation imposes public hearings along the way to approval, and those are opportunities for neighbors to try quashing applications with complaints about lost parking, smells, rats, and noise. That in turn provides more opportunities for employment for lawyers and expediters. The local city council member, who must sign off on each application, can ask the entire city council to vote on a particularly problematic sidewalk café (though not on its roadway cousin). DOT predicts that such interference will be rare, and the vast majority of applications will sail through. Maybe, but New Yorkers are resourceful in finding ways to say no. Opponents will quickly figure out how to turn every parking spot and table into a battleground. The outdoor dining scene needs to be tamed and controlled, not snuffed out by obstructionists. We can’t have a system that’s subject to political hijacking.

Streeteries are just one component of the post-pandemic commons, where foot by foot and spot by spot, we claw back public space from the monopoly of cars. Like cities all over the world, New York keeps having to renegotiate competing, and increasing, demands for public space without being able to create much more of it. Deleting parking spaces and traffic lanes has proven to be a rich, if contested, source of acreage for a slew of other uses, including electric vehicle charging stations, waste containers, package delivery zones, and yes, outdoor dining. The city has been turning parking into plazas since 2007, and the pandemic practice of opening car-free streets led to the Open Streets program, which boosts retail businesses and gives New Yorkers a taste of a fewer-car future. That’s one innovation that remains popular and is still going strong: There are now 90 plazas and more than 200 open streets in all five boroughs, and the Adams administration has committed $375 million to public space improvements and turned over another million square feet to pedestrians. These changes, broken up into pocket projects and distributed around the city, can feel sporadic and meager on the ground, but they add up over time.

Plazas, open streets, wider sidewalks, roadway dining—each of these programs has its own separate history and administrative boundaries, but when they are numerous and close enough, they flow gratifyingly together, merging the official and the informal. On a recent afternoon I walked through the newish Montefiore Square at Broadway and 137th Street, a handsomely designed, sloped mini-park by SWA/Balsley, where a handful of middle-aged men were blissing out to music by the Argentinian folk singer Mercedes Sosa. Up the street, an intergenerational cluster of neighbors had colonized the sidewalk with beach chairs and a soundtrack of vintage Colombian cumbia. A few more blocks took me past a knot of young people lounging around a parked SUV broadcasting Afro-Mexican hip-hop, to Johnny Hartman Plaza, the intersection of Hamilton Avenue and 143rd Street that’s been pedestrianized with planters, paint, and café tables. The neighborhood’s social ecosystem looks organic, but it’s the work of a dozen city agencies and neighborhood groups, millions of dollars, and years of planning. (The work isn’t done: I noticed a brisk open-air drug trade taking place along West 144th Street.)

Change is a gradual, uneven, and protracted process, one that doesn’t necessarily reveal itself in before-and-after snapshots from 2020 and 2024. The city is always trying to formalize the casual and eliminate the slovenly, without sacrificing authenticity. It’s a delicate operation that takes time and we don’t always get it right. And yet, hesitantly and much too slowly, New York is finally enshrining the realization that the city’s soul resides in its streets and needs room to thrive there.

Source link