A Typical Greenpoint Rowhouse That Hides an Artist’s Loft

“This house, when you see it from the outside, can be very misleading,” said broker Ewa Mydlarz, who met the owners in the neighborhood seven years ago.

Photo: Dan Osborn/VHT

The typical postwar Greenpoint apartment building contains six units, three on each side of a tall, narrow stair. The exteriors are often clad in vinyl siding — a sensible way to keep out the rain and the fog coming off the East River. On Clifford Place, a few blocks west of Manhattan Avenue, a row of three buildings seems to fit the format. Only, at No. 16, a porthole window on the top floor is a clue that the interior is very different.

The building was designed and built in 1986 by Brian McMahon, an architect schooled at Pratt and trained in historic preservation who worked as a contractor and fell in love with Greenpoint — buying up 14 buildings across the sleepy Brooklyn neighborhood and marrying a Polish émigré who owned a grocery on Manhattan Avenue. No. 16 was the home that McMahon built to serve as a showpiece for what he could do. “I wanted to take the worst house in Greenpoint and fix it up and make a story out of it,” said McMahon. The “story” would have two morals: one, that Greenpoint was the next Soho, a place where artists could live and work, and two, “that a person can fix up anything.”

When McMahon bought No. 16, it very well could have been the “worst house in Greenpoint.” A fire had gutted the place, taking out the top floors but saving the dismal façade. He made a preservationist’s decision to keep the exterior intact, for the sanctity of the row. Inside, he created a sunny, simple artist’s loft inspired by Charles Gwathmey and Robert Siegel’s stark beachfront houses (made immortal in Weekend at Bernie’s). Four upper units and the ground-floor unit on the right side became a single, airy owner’s triplex — 85 feet deep and as wide as 23. No walls broke up a primary suite that stretched the entire top floor. Most of the living area was a full three stories high and framed by an industrial staircase that cut down diagonally. “I wanted a stair where the lady of the house could make a grand entrance to a party of 200 people.”

Left: the building that architect and developer Brian McMahon bought in 1986. Right: The row today. A circular window gives a clue that the interior is different, and what seems like a bay window is actually a balcony. “I intentionally wanted to play with the repetition and rhythm,” McMahon said. From left: Photo: Brian McMahonPhoto: Adriane Quinlan

Left: the building that architect and developer Brian McMahon bought in 1986. Right: The row today. A circular window gives a clue that the interior i…

Left: the building that architect and developer Brian McMahon bought in 1986. Right: The row today. A circular window gives a clue that the interior is different, and what seems like a bay window is actually a balcony. “I intentionally wanted to play with the repetition and rhythm,” McMahon said. From top: Photo: Brian McMahonPhoto: Adriane Quinlan

The living area McMahon created was three stories high and looked into the ground-floor gallery, which was showing the sculptures of Jim Nickel during this shoot in the 1980s. Brian McMahon.

The living area McMahon created was three stories high and looked into the ground-floor gallery, which was showing the sculptures of Jim Nickel during…

The living area McMahon created was three stories high and looked into the ground-floor gallery, which was showing the sculptures of Jim Nickel during this shoot in the 1980s. Brian McMahon.

To draw 200 people, McMahon turned the ground floor into a foyer that doubled as a nonprofit art gallery, which he called FFA for “Friends, Family, and Acquaintances.” He had always been friends with artists, but his wife Teresa pulled him into a local enclave of persecuted immigrants. “We became an important resting spot for important Polish artists,” McMahon said — and he meant that literally. The ground-floor unit that he had not combined into his owner’s suite became a place where artists and friends could live rent-free. Shows included work by Andrzej Czeczot, Jan Sawka, and Allan Rzepka. Isamu Noguchi and Keith Haring stopped by. The Polish American Arts Society eventually recognized McMahon for his “contribution to the enhancement of Polish art.” When a Newsday reporter visited, he called McMahon the “vanguard of a revitalization” of the neighborhood alongside a shot of the family picnicking on the living-room floor. This was all “strategic,” said McMahon, who at the time had more than a dozen other properties. “I did want to attract artists, so what better way to do it than to showcase your own house?” But the optimistic developer had snapped up property at high interest rates, and when the market crashed, he was forced to sell off his buildings one by one. He saved 16 Clifford Place for last, listing it in 1990.

Kenro and Sue Matsuki met when they worked in a travel agency and spent lunch breaks visiting art galleries nearby.

Photo: The Matsuki family

Kenro and Sue Matsuki have been living there since 1991. Kenro uses the long top floor as a painting studio and office, and Sue uses one of the two bedrooms that McMahon built for his children as her office, where she has managed a hobby in cabaret; one wall is covered in framed Playbills and posters. The huge living space became an asset for her: A band can set up on the third-floor balcony that peers over the living area, and Sue has sung in a space that feels as big as a theater. Downstairs, the front of the former gallery space holds Kenro’s moody artwork, and the back has served as a mother-in-law suite that looks out into the small backyard — where Sue’s friends from the singing world have stayed, and where Kenro’s mother lived for years.

They’ve updated the kitchen and made other tweaks, but they’ve kept McMahon’s vision intact. Looking over their floor plans from his new home in Stillwater, Minnesota, where he and his wife Teresa settled and raised a family of four, McMahon says he felt nostalgic. “If I had kept those buildings, I’d be a multimillionaire,” he said. “I knew Greenpoint was going to take off. There was never any doubt in my mind.”

McMahon installed double doors he found at an antique salvage store so he could install large artwork in what was then the entrance of his nonprofit art gallery, FFA. Kenro Matsuki has used the space to display his own artwork, shown on the left.

Photo: Dan Osborn/VHT

Stairs from the gallery lead into this high-ceilinged living area. “When we first walked upstairs, there was so much ‘wow’ factor,” remembered Sue Matsuki. “I had moved in mentally the minute I walked in here.”

Photo: Dan Osborn/VHT

Kenro Matsuki has used the top floor as a painting studio and home office. He ran his own travel agency and never stopped painting expressive multimedia abstractions.

Photo: Dan Osborn/VHT

The Matsukis have not changed much. The top floor is 85 feet deep, but there are only a few walls, which hide a bathroom (to the right). Brian and Teresa McMahon used the floor as their primary suite.

Photo: Brian McMahon

The top floor today. Sliding doors give access to a balcony over Clifford Place.

Photo: Dan Osborn/VHT

The bookshelves from the other angle, showing the back of the bathroom with a lofted storage area and a closet. A playful porthole window looks in over the tub.

Photo: Brian McMahon

The Matsukis hid the porthole of the bathroom with a painting (left). At parties, guests come up to play pool.

Photo: Dan Osborn/VHT

The Matsukis caught the marlin in Mexico on one of their many travels. They met working at a travel agency in midtown; Kenro, an art student, would take Sue to galleries nearby. Sue, a former dancer who sang in choruses, was smitten at first sight.

Photo: Dan Osborn/VHT

Off the main living area on the second floor, one of Kenro’s paintings hangs next to masks the couple bought in Mexico and hung over a long dining-room table.

Photo: Dan Osborn/VHT

The open kitchen, which the Matsukis renovated ten years ago. The railing to the right holds stairs that lead down to the ground floor. Behind the kitchen, at the front of the house, are three bedrooms. Off to one side is a pantry with a laundry area.

Photo: Dan Osborn/VHT

The primary bedroom looks over Clifford Place, a sleepy one-block-long stretch of apartment buildings just off Meserole Avenue. The gridded painting on the left is Kenro Matsuki’s ode to Agnes Martin.

Photo: Dan Osborn/VHT

Sue Matsuki’s office looking over Clifford Place. After she met Kenro at a travel agency, she managed a law firm by day and had a side hustle as a performer. A former dancer and chorus singer, she served as a supernumerary at the Metropolitan Opera and eventually found her niche in cabaret.

Photo: Dan Osborn/VHT

Downstairs, the former gallery serves as a mother-in-law suite, with its own kitchen and bathroom. The sliding doors lead to the backyard.

Photo: Dan Osborn/VHT

The mother-in-law suite. Kenro, who was born in Tokyo, hosted his mother here for years.

Photo: Dan Osborn/VHT

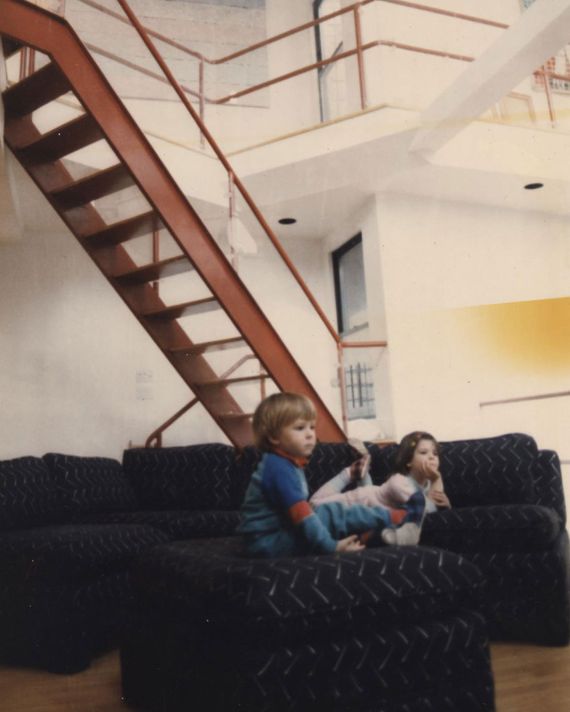

McMahon’s daughter Katarzyna was born shortly before the family moved in, and his eldest son Tadeusz was born shortly after. The family eventually moved to Minnesota.

Photo: Brian McMahon

Source link