A Hamptons Modern With Roots in I.M. Pei

The architect Robert Lym Jr. didn’t go after fame. The museums, libraries, and hotels he helped design were branded under the name of his boss, I.M. Pei. Hired in the late 1950s, Lym stayed until his retirement, in 2002, when he’d ascended to the title of head of interiors. College friends with Alexander Calder, whose mobile hung in his Sutton Place apartment, Lym was a creative by temperament: highbrow and fun, according to his nephew Glenn Robert Lym, who followed him into architecture. Weekends were spent at the opera or at parties thrown by socialite Kit Gill or Philip Johnson, whose social swirl of gay, highbrow New Yorkers overlapped with his own. He was also selective about taking on extra work, designing just three homes under his own name. One was renovated beyond recognition, while the second was razed to build an airport. The third is now on the market.

The simple cedar-walled home at 126 Noyac Path in Water Mill was not designed to be a calling card. Invisible from the street for most of the year, the 1971 house is unknown even to most locals and doesn’t seem to have ever been published in a magazine. “It’s kind of a mystery,” says the critic Alastair Gordon, who researched the house for his 2001 book on modern homes in the Hamptons but “never could find anything about it.” This winter, the designer Timothy Godbold happened to see it on one of the scouting missions that he runs for a nonprofit documenting modern homes(when the leaves are bare, they’re easier to spot): “I thought, Wow, how do I get to that house?”

Glass doors open to decks that fan out from the house and are each 20 feet wide.

Photo: Saunders & Associates

The one-story home was a solid square, built low to the ground, on farmland that lacked much landscaping: no pool, no driveway, no banks of flowers. Like a later Myron Goldfinger mansion, the house seemed to hide from the world behind a skin of vertical wood planks. Four tiny wings hold a kitchen and three tiny bedrooms, whose windows are shaded by fins of wood. Between them, on each side of the square, sliding glass doors open to 20-foot-wide decks that lead down to the grass. The simplicity seemed totally “unpretentious,” Godbold says. Intrigued, he photographed the house and uncovered floor plans at the town clerk’s office that showed how the symmetry worked inside, with a living room at the center and a bedroom in each corner.

The plans had been signed by Lym, whose name appears infrequently online. It’s also not a common name, and Godbold messaged Glenn after finding his site. He had heard of the house firsthand and saw a clear connection to his uncle’s work. The open living area, walled on four sides by glass sliding doors, had a foothold in the “glass box modernism” that Lym would have studied at Harvard, and the pinwheel floor plan was similar to a Pei museum in Syracuse that Lym had talked about working on. It opened in 1968, the year that Lym filed the first plans for 126. “Never having seen it, I realized it was Bob. I just didn’t realize it would be as tightly woven together as Bob,” says Glenn. He saw his uncle most clearly in the bedrooms, which shaded themselves from view — not just by the fans that obscured the windows — but by how doors faced hallways, rather than into the living room, as if Lym was concerned about what might happen if someone pulled open a door. “The house was very, very tight, and there’s all of this control,” says Glenn.

Bedrooms are cozy and private, following the Horace Gifford model of making the home more social by pushing the fun into an open living area.

Photo: Saunders & Associates

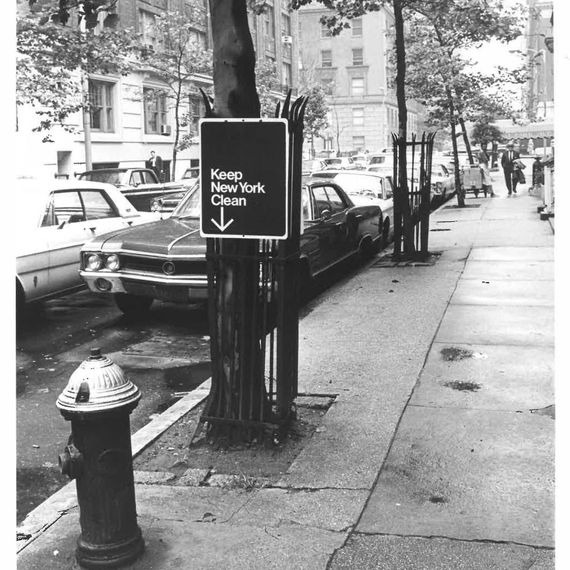

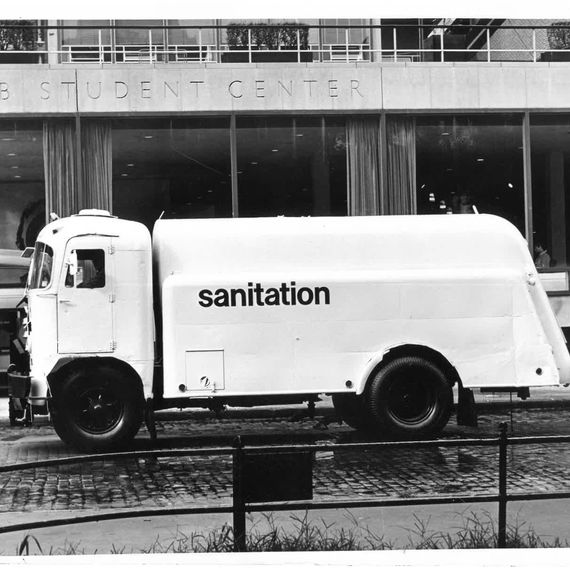

Lym probably met his client at work. Walter Kacik was a graphic designer who joined Pei’s office in the late 1950s, as Pei was rethinking how buildings could incorporate signage by hiring graduates from the Yale School of Design — Kacik’s alma mater before a stint in the Army. When Kacik left the firm, in 1962, he found success, earning lucrative commissions to rethink corporate logos and starting an eponymous firm that won a city contract to redesign the garbage truck. He rebranded the old fleet as clean, white, and stamped with “sanitation” in lowercase Helvetica — a bold choice for 1968, which he made to associate the fleet with a “kind of purity,” he said. He also rebranded himself, going back to his family’s 19th-century spelling (Kacik) rather than his father’s Anglicized “Kasick.” While other gay men of his generation were leaving to create a kind of utopia on Fire Island, Kacik, who grew up in rural Pennsylvania, may have wanted a retreat on farmland, says Nancy Kasick, who married his nephew and visited the house a few times over the years: “He was a brilliant man and ahead of his time.”

Kacik changed the look of his city with simple signage. From left: Photo: NYC Department of SanitationPhoto: NYC Department of Sanitation

Kacik changed the look of his city with simple signage. From top: Photo: NYC Department of SanitationPhoto: NYC Department of Sanitation

He was also generous, says Nancy Kasick. Glenn says that his uncle stayed with Kacik every summer. If he fell for the house, it might have been because it was where he met his partner of 38 years, who had shown up when the place was still under construction, asking to borrow a clove of garlic. It was Arthur Coake, who was staying nearby and who died in 2017. Lym died in 2006. And Kacik died in 2012, leaving behind his partner, the publisher David James Walsh, who died last year.

Nancy Kasick‘s husband kept snapshots of the house, which date back to its construction. From left: Photo: Courtesy Kasick FamilyPhoto: Courtesy Kasick Family

Nancy Kasick‘s husband kept snapshots of the house, which date back to its construction. From top: Photo: Courtesy Kasick FamilyPhoto: Courtesy Kasick…

Nancy Kasick‘s husband kept snapshots of the house, which date back to its construction. From top: Photo: Courtesy Kasick FamilyPhoto: Courtesy Kasick Family

The project of selling the house has fallen to broker Drew Green, who marveled at the unique design. (“It’s the most symmetrical house I’ve ever seen, and it’s shaped like a fidget spinner.”) But he might not necessarily be able to save it. The home is just 2,200 square feet, and he has seen buyers and developers tear down small houses to make the high cost of land here worth it. It’s on the market for $3.45 million — and Green is listing it with three other lots that the couple also owned, which are priced between $2.3 million and $3.45 million, or $10.5 million for all four. If houses go up on that land, the home will be more visible — no longer a hideaway, but the calling card that Lym never asked for. “It’s not a house meant to be seen on the outside and make an impression,” says Glenn. Which these days, in the Hamptons, means it stands out. “What makes it amazing is the simplicity,” says Godbold. “It just dissolves into the landscape.”

Price: $3.45 million

Specs: 3 bedrooms, 2 bathrooms

Extras: Four decks that add 1,180 square feet of outdoor space; two acres of land allow room for a pool and tennis court

Listed by: Drew Green, Saunders & Associates

The designer Timothy Godbold stumbled on the house and admired it for its “simplicity,” with slivers of windows in the bedrooms that reminded him of windows in “a Brutalist modern church.”

Photo: Saunders & Associates

Guests enter on the other side of that freestanding bookcase (right) and walk to the center, where an open living area is lit by sliding glass doors on two sides that lead down to decks.

Photo: Saunders & Associates

The wood outside would have been identical to the wood inside when the house went up, but the exteriors have since faded.

Photo: Saunders & Associates

Each side of the square house has a wall of glass doors and a deck, framed on two sides by bedroom wings. Behind the fireplace is a dining area.

Photo: Saunders & Associates

A view down the dining room toward a simple kitchen.

Photo: Saunders & Associates

In the kitchen, light comes from a skylight. The couple had an “affinity for collecting clocks,” says broker Drew Green.

Photo: Saunders & Associates

Two of the bedroom wings include a bathroom, and a third has access to a laundry room.

Photo: Saunders & Associates