Inside the Hamptons’ Zoning Wars

In October 2019, Billy Hajek, the East Hampton village planner, inspected a property on a one-lane road running along a narrow strip of land separating Georgica Pond from the ocean. On it sat a shingled vacation house, which dated to a time before strict wetlands regulations and had been built close to the pond, where it had long been hidden by a tangle of tall reeds, swamp bushes, and honeysuckles. Since buying it for $10.3 million, a new owner, the real-estate developer Harry Macklowe, had set about renovating it according to his own tastes. He painted the whole thing — even the roof — a blistering white. Along the road, he replaced a rustic farm fence and unruly brush with a privet hedge and a neat line of seagrasses, irritating his very wealthy neighbors, who complained about poor drainage. Hajek had come to assess what had been going on behind the privet. What he discovered kicked off a six-year saga of infighting, litigation, and landscaping. The Macklowe house now sits on the market, a white elephant, priced at $32.5 million but because of its zoning violations effectively impossible for its owner to sell.

For as long as humans have owned property, they have been arguing over it, but land-use disputes come on a different scale in the villages and hamlets on the East End of Long Island, where the cost of entry is in the millions, regulations are persnickety, and no one is accustomed to hearing the word no. Summer neighbors are often fighting one another while simultaneously trying to avoid the notice of the small-town government employees and appointed board members, who themselves are charged with policing the activities of homeowners who can afford almost anything and are lawyered up to the hilt.

The Hamptons Issue

See All

Even one of his attorneys would later admit that as a developer, Macklowe was well aware of the need for permits and the intricacies of the zoning code. Most of his property was within 150 feet of the pond shoreline, the current wetlands boundary, which meant that extensive alterations would require a time-consuming variance application. But Macklowe, 79 when he bought the house, is not known for his patience. He had purchased the home in the midst of a bitter and expensive divorce from his then-wife, Linda, who had kept their mansion on the same body of water, and he wanted a place to vacation with the French fashion executive he later married. The village government had granted him permission to clear some phragmites, a type of invasive grass, on the condition that he replace them with native vegetation. Instead, as Hajek recorded in photos and a memo, Macklowe clear-cut much of the land around the house and put in a floating dock and a kayak rack. He built white concrete patios on two sides, enlarging the house’s coverage area by thousands of square feet. He replaced the pool shed with a pergola and outdoor shower.

Hamptons property owners have developed a variety of strategies to defend what is hidden behind their hedges. They deny. (“Cabana? What cabana?”) They shift blame. (It was the fault of the contractor — always the contractor.) Or they hire lawyers and fight, which is the option Macklowe chose. First, he went to the village’s zoning board of appeals, where his attorney argued his alterations were not really so drastic. When the board rejected him, Macklowe sued. After three years, a judge found in the village’s favor, but Macklowe filed a second lawsuit, which was dismissed on June 10. He’s still haggling with the zoning board over potential remedies. In such situations, when a client has the resources and the inclination to go round after round, small municipalities have to decide whether to settle or stand on principle, draining their budget. “Once you get into litigation, especially with titans of capitalism, the towns have to hire firms that can compete,” says Robert Connelly, a former municipal attorney now at the high-end real-estate law firm Romer Debbas.

In East Hampton, though, Macklowe has found a village that is unwilling to yield. Partly this can be attributed to a lack of community sympathy, given the glaring nature of his transgressions against local law and local taste. (“From a distance, that’s what you see when you fly in by helicopter,” says one East Hampton resident. “Who paints their roof white?”) There is also a sense that Macklowe is a repeat offender. In New York, in the 1980s, the developer notoriously demolished four Times Square buildings in the dead of night, to head off a moratorium on tearing down SROs, for which he paid millions in fines. In the 1990s, a dispute with Martha Stewart, his neighbor at his former Georgica home, over plantings along a property line culminated in an incident in which Stewart allegedly backed her car into Macklowe’s landscaper. (No criminal charges were filed.)

Macklowe’s most determined opposition has come from the zoning board and in particular a member of it who’s from his own world. Joe Rose belongs to one of New York’s old real-estate families, and he started coming out for the summers as a kid in the early 1960s. He became a civic activist in New York City and during the 1990s was chairman of the Planning Commission, working on projects like the revival of Times Square. He went on to his own career in real-estate development in the city, but he now lives mainly in East Hampton, where he volunteers his time to sit in judgment of dormers, fences, and patios. Although Rose was careful not to discuss Macklowe with me, even off the record, for fear of saying anything that would complicate the case, he has a history of run-ins with the developer and his votes make his stance clear.

Rose tells me he feels called to care for “this incredibly special sliver of land.” He is voicing an age-old lament: The money is coming, the money is bigger, the money is spoiling the summer. The last generation’s spendthrifts have become this generation’s scolds, as controversies recur over the same parcels of land with new names in the old roles. But the people who have been in the Hamptons forever, like Rose, contend that there’s something different about this latest wave. “Everyone wants more,” Rose says. Not just the pool, but a pool house. Not just a tennis court, but also padel or pickleball. When the money involved is practically infinite, nothing is out of bounds. To the acquirers, the local code, like the ground, is made to be broken.

Locals are trying to save a historic Norman Jaffe home from being demolished after another bit the dust. Photo: Corcoran.

Locals are trying to save a historic Norman Jaffe home from being demolished after another bit the dust. Photo: Corcoran.

Cody Vichinsky, a co-founder of Bespoke Real Estate, says that buyers in the segment of the market he specializes in — properties priced at $10 million and above — tend to follow a familiar routine. “In their mind,” he says, “they’ve seen other homes, and it’s ‘I want a pool, I want extra bedrooms, I want blah, blah, blah.’” The detail work of permits? That’s a job for the help. Sometimes, he says, a buyer might say, “Hey, listen, I understand the code, and I want to be able to do these things, and if I have to get a smack on a wrist that’s insignificant, that pales in comparison to my utility of joy …” Well, in that case, fuck it.

They’re happy until a code inspector knocks at the door. “There’s horror story after horror story,” says Southampton attorney John Bennett, a garrulous East End lifer who has made a practice of representing wealthy homeowners in front of local boards. When I first called him up, Bennett told me he had just given a talk on land use. “I started off by saying, which got sort of a laugh, that no matter what anybody’s political leanings are, generally when they come into my office and talk about their property — their property — they’re all conservative Republicans,” he said. Bennett’s family has lived in the Hamptons since long before anyone called them that. He followed a common path into land-use law, serving as the town attorney for Southampton in the 1980s before setting himself up as the lawyer whom summer residents come to when they need a local guy. The East End of Long Island has a confusing patchwork of governments, and within some towns there are incorporated villages, political islands that set their own — usually stricter — land-use regulations.

The people who run the governments, locals like himself, grouse about the construction on Meadow Lane, along the Southampton shoreline, which has lately molted into a brood of architectural monstrosities known as “Billionaires’ Row.” They say that Duryea’s Lobster Deck is ruined now that it’s owned by the CEO of the private-equity firm Apollo Global Management. They are driven crazy by the incessant pock-pock of pickleball. (Municipalities have lately been passing pickleball ordinances requiring soundproofing.) But Bennett is there to help his clients build all that the codes will allow, which is still plenty — the maximum floor area for a house is 18,000 square feet in Southampton.

Bennett has handled several controversial cases on Billionaires’ Row. There is the ironically named Bliss House, designed by the modernist architect Norman Jaffe, which the owner is seeking to demolish over preservationist objections. “We did a four-year battle, and finally the lower court said, ‘Take it down,’” Bennett says. (An appeal was denied in March.) Another client was a since-imprisoned real-estate developer whose Meadow Lane neighbors complained his beach house was too tall. “Reasonable minds can differ about the architecture of the house, but it was fully approved,” Bennett says. Afterward, the village tightened its zoning rules; the tall house’s current resident, New England Patriots owner Robert Kraft, has been frustrated in his desire to add an elevator. (Bennett is not involved in the Kraft case.)

Bennett says that sometimes a client who wants something that requires a zoning-board approval will ask him, “Why shouldn’t I just do it?” He discourages that path as “very, very, very risky.” You might get away with it, but if you want to sell the place, some East End municipalities have ordinances requiring that you secure a new certificate of occupancy from their buildings department before a deed can be transferred. If an inspection turns up unauthorized alterations, you could find yourself stuck. This is the bind Macklowe is in. Or one of your neighbors might rat you out to the authorities. This happens frequently in the Hamptons, where there are regular explosions of acrimony between the haves and the have-a-lot-mores.

One of Bennett’s clients, Adam Shapiro, learned about local land wars the hard way. Shapiro, a former Goldman Sachs guy, runs East Rock Capital, a Manhattan-based firm that manages around $4 billion for a handful of ultrawealthy families. In 2015, he purchased a 7,200-square-foot residence in Bridgehampton for $12.3 million. The property, in an area of rolling fields north of Montauk Highway, came with an adjoining nine-acre agricultural reserve. Shapiro imagined he was buying a farm. What he really acquired was a bundle of legal problems, surveillance, and strife.

The conflicts began when Shapiro discovered a passion for horticulture and decided to expand on a previous owner’s plan to operate the reserve, known as Butter Lane Farm, as a tree nursery. The land was protected by a conservation easement that had been put in place two decades before, when a developer made a deal to build housing around it. The easement allowed for commercial farming, but Shapiro also wanted to build structures that would need town approval. He was met with extreme hostility from his neighbors.

They objected most strongly to Shapiro’s preliminary application to build housing with three bedrooms for workers, which he contends is vital to maintaining the full-time staff the farm needs. The neighbors countered that the terms of the easement specifically forbade residential construction, as Shapiro should have known. “He’s a sophisticated money manager,” says Meredith Berkowitz, a Manhattan attorney specializing in capital finance who is one of the opposed property owners. “He knows how to do due diligence.” Berkowitz tells me that when she and her husband, who live on the Upper East Side, shopped for a summer home, they specifically looked at properties adjoining agricultural reserves, because she loved the country. Then Shapiro came along.

The battle intensified during the COVID pandemic, when many summer residents temporarily relocated to their vacation homes and Shapiro’s suspicious neighbors could closely monitor developments on the farm. While the lockdown kept the town’s offices closed, workers showed up and constructed a chicken coop and other animal enclosures without permits. A children’s playhouse popped up near the fruit orchard. And a couple days before Christmas, the neighbors noticed that four alpacas had appeared like fuzzy magi. Berkowitz and other neighbors surreptitiously recorded all these developments in snapshots and video clips, which they later posted on a website, savebutterfarm.org. One of the videos showed Shapiro’s children chasing the alpacas around the reserve in an ATV. A Manhattan dermatologist named Michele Green, who had paid $4.6 million for a house next to the farm, filed dozens of photos with the town-planning department, scrawled with handwritten notations like “more waste and debris” and “2 years of Porta Potty.” Shapiro complained to the town about the invasion of his privacy, filing affidavits that accused Green of harassing his laborers by filming them through her privet hedge. “Why is the manure structure so near my property,” another neighbor, Niko Elmaleh, wrote to the zoning board. “I am very concerned about the odors which most certainly will deny my quiet enjoyment of my home for which I paid millions of dollars.” (Shapiro contends alpaca poop is “odorless.”)

The morning after Memorial Day, Bennett met me at Butter Lane Farm along with his client, a well-scrubbed man with a neat salt-and-pepper beard. Shapiro regarded me warily at first, but he warmed up as he showed me around the farm. “We were probably naïve about how much work this would all be,” Shapiro said. Some of the trees he had inherited from the previous owner were infected with beech-leaf disease, a blight caused by parasites. “There was something about trying to figure out what went wrong, why these trees died, how we take what we found to make it better, that kind of — for lack of a better word — became a mission.”

Shapiro said he is focusing on trees with “high commercial potential” and showed me some of the rare and expensive specimens he has been cultivating: spiny Monkey Puzzles, shin-high sequoia saplings, a fragrant species of magnolia. The farm animals, he said, are just a sideline. “If you want to get your kids interested in your farm, alpacas help a lot,” Shapiro told me as the animals, all fur and legs, clomped around their pen. The previous weekend, in order to clear the books of an outstanding notice of violation, he had demolished a shelter built for them. The alpacas didn’t like being inside anyway, he said. “Farming can be an intensive business,” Bennett had told me. The neighbors? “They don’t understand what farming means.”

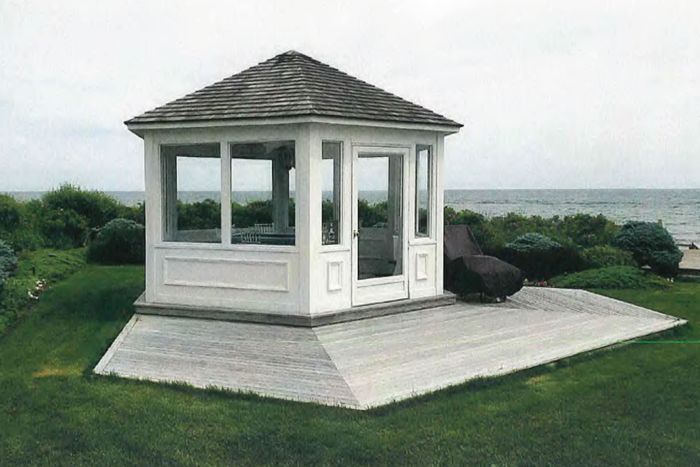

Zoning rules have prevented Robert Kraft from installing an elevator. Carl Icahn allegedly ignored them when he built his gazebo. Photo: Google Maps (Kraft); Suffolk County Clerk (Icahn).

Zoning rules have prevented Robert Kraft from installing an elevator. Carl Icahn allegedly ignored them when he built his gazebo. Photo: Google Maps (…

Zoning rules have prevented Robert Kraft from installing an elevator. Carl Icahn allegedly ignored them when he built his gazebo. Photo: Google Maps (Kraft); Suffolk County Clerk (Icahn).

Some property disputes between Hamptons neighbors have gone as far as to become Hamptons lore. In the early 1990s, for instance, there was a blue-blooded feud between Jackie Onassis’s sister Lee Radziwill and a beachfront neighbor who wanted to build a Rafael Viñoly–designed mansion that would obstruct her view. (The house was built and is now owned by hedge-fund manager Daniel Loeb.) For every argument that breaks into the open, though, there are many more offenses that no one knows about. In general, the wealthier the owner, the more private the property, and the greater the incentive there is to build first and seek permission retroactively — and only if someone complains.

In 2012, a volunteer firefighter who responded to a call from the Creeks, the investor Ron Perelman’s 58-acre estate in East Hampton, discovered that Perelman had constructed or renovated many buildings without permits, including a 5,800-square-foot habitable barn, a 4,200-square-foot carriage house, and a small synagogue. Attorney Leonard Ackerman, who represented Perelman and has been involved in many big Hamptons land-use cases, likes to say that he practices “forgiveness law.” For Perelman, forgiveness at the Creeks meant ripping six bedrooms out of the carriage house, tearing down part of a cabana, and revegetating 70,000 square feet of illegally cleared wetlands.

Often, though, once something is there, it is very difficult to make it go away. Consider the case of Carl Icahn’s gazebo. Since the 1990s, the corporate raider has owned a beachfront home off Lily Pond Lane, one of the most expensive streets in East Hampton. In 2019, a code-enforcement officer who had come out to inspect a pool on the property noticed an enclosed structure with a pyramidal roof on an elevated wooden deck, right up against the protected dunes. The Icahns responded, essentially, Oh, that? It had been there since around 2007.

The matter of the gazebo took until 2022 to reach a zoning hearing, at which Gail Golden-Icahn testified that it had been built to allow her and her husband to eat their breakfasts without fear of being besieged by swarms of yellow jackets. “It has not bothered anybody; it has been there forever,” their lawyer said. The argument seemed to be convincing the board, at least according to Icahn’s later legal filings, until a single member — Joe Rose — spoke up and said he was bothered, having walked past the gazebo many times. “I think it is highly — I know it is highly — visible from the beach,” he said. The variance request was voted down. Icahn sued in New York State court, and when he lost, he went on to appeals that have yet to be resolved, all so he could keep his 400-square-foot breakfast nook.

“I don’t take any pleasure in saying ‘no,’” Rose told me when we met to speak about his role on the East Hampton board at the Golden Pear Cafe. We drove to the ocean, where he showed me the stately home where his family summered when he was a child. It was not far from Icahn’s compound and other places belonging to famous names: Bon Jovi, Blinken, Spielberg. Rose talked about preserving “the commons” and said he realized his approach to land use frustrated some who wanted rubber-stamp approvals. But he didn’t seem to mind being a killjoy. “I think there shouldn’t be different sets of rules for different people,” Rose said. By which he means people like him.

To some who appear before the zoning board, Rose’s attitude can seem overly exacting. At its meeting in April, the hedge-fund manager John Griffin and his wife, Amy, asked for a small height variance to replace one lawn sculpture with another, a 15-foot-tall Carol Bove statue that incorporated a polished steel disk. The board appeared ready to sign off when Rose jumped in to ask, “Has anyone looked at or thought about the issue of what happens when the sun shines down on it?” (Upon reflection on reflection, the variance was unanimously approved.) In 2024, Macklowe’s attorneys wrote a letter seeking Rose’s recusal from decisions involving the developer’s house, claiming he had made comments that suggested he had “prejudged” the case. Although the letter didn’t mention it, Rose had been the chairman of the community board in Times Square back when Macklowe demolished those buildings without permits. Rose told New York in 1989 that Macklowe exemplified “outlaw-developer syndrome.”

“I’m not intimidated,” Rose told me, speaking generally. “Just because a big shot demands something or is irritated by a regulation does not mean we have to bow and scrape.”

Neighbors objected to construction at Butter Lane Farm in Bridgehampton, including to an enclosure meant for alpacas. Photo: Courtesy of the Author.

Neighbors objected to construction at Butter Lane Farm in Bridgehampton, including to an enclosure meant for alpacas. Photo: Courtesy of the Author.

Meredith Berkowitz pointed to a white municipal truck parked next to a row of copper beech trees. “There’s code enforcement,” she said. She had brought me up to the second-story deck of her Bridgehampton vacation home to peer over her rear privet hedge, which offers her an elevated view into Butter Lane Farm. She guessed that an inspector was visiting the property to confirm the demolition of the unpermitted animal enclosures. “That’s where the chicken coop was,” she said, pointing to a dirt patch.

When I had spoken to Bennett previously, he had said it was “really the height of arrogance” for people to buy an expensive house in the country and then complain about farming. But Berkowitz says she is not opposed to farming and has nothing against chickens and alpacas. She contends that the reserve is too small for animal husbandry under the town’s zoning and that the easement says nothing about allowing pets. It looks to her as if Shapiro is using the cover of farming to develop the land for his family’s enjoyment. She questions whether the farm housing was really for farmworkers, saying that amenities in the original design, including an outdoor kitchen, made it look more like a guesthouse. “It dwarfed in size and elegance any agricultural housing in the nation,” Berkowitz says. The neighbors are also suspicious of his greenhouse proposal. Shapiro says it is necessary for nurturing exotic trees during the winter, but in drawings submitted to the town, it appeared to have chimneys, and who had heard of an arboretum heated by fire? (Shapiro’s representatives say his opponents are misinterpreting preliminary plans and conceptual sketches.)

The Bridgehampton Civic Association, which Berkowitz joined, has been advocating for stricter enforcement of agricultural easements ever since another owner of a reserve, Howard Lutnick, the future Commerce secretary, tried to build an 11,000-square-foot barn — allegedly for his car collection — and a basketball court on his land. (In 2016, after pursuing lawsuits for years against the town and board members, Lutnick got most of what he wanted in a settlement.) The local authorities “are giving in because they’re afraid of the lawsuits,” Berkowitz says. Hamptons property owners “have endless deep pockets to fund this.”

In the case of Butter Lane Farm, Bennett and Shapiro have come up with an inventive way to work around the town. They are currently seeking approval from the Suffolk County government for the reserve’s inclusion in a special agricultural district, which would prevent the municipality from placing “unreasonable restrictions” on it in the land-use process. And if that doesn’t work, there is an ongoing lawsuit. Bennett can cite precedents favorable to Shapiro. The Town of Southampton recently agreed to a legal settlement with the real-estate investor Lloyd Goldman, carving out an exception to an easement for agricultural housing on his farm in Sagaponack. As for livestock, there was a favorable ruling from the planning board in the case of developer Jed Walentas and his sheep.

Harry Macklowe’s folly could end up providing the ultimate test in the conflict between wealth and the code. It would appear the zoning board has leverage to extract concessions, because Macklowe is trying to sell the house and it has been lingering on the market for more than a year. Vichinsky, one of the brokers handling the listing, says Macklowe decided to sell simply because he and his wife now spend more time in Europe. But a series of lawsuits and liquidations involving Macklowe’s New York property portfolio suggest he has a financial motive to move quickly. One lender, to whom Macklowe owed a reported $90 million, alleged in a February civil-court filing that the developer had pledged to sell the East Hampton house to partially satisfy his debt. (The lawsuit was discontinued in June.) Since the village has one of those ordinances requiring a house to pass an inspection for a new certificate of occupancy, Macklowe legally can’t close a sale until he clears his violations. No buyer is going to offer $30 million for a house they can’t move into.

Macklowe’s latest lawyer — the forgiveness specialist, Ackerman — has made a series of settlement proposals to the East Hampton village zoning board. His client is willing to rip out the lawn, replant wetland grasses, shrink the patio, move the kayak stand, improve stormwater drainage, and otherwise return the property to its former condition or better. But at a June 13 zoning-board meeting, the inspector Hajek said that Macklowe’s “disrespect to the village code” required further concessions, including posting a bond that he would forfeit if he did not fulfill his promises. “Given the history of this site,” Rose said, “we have to be especially careful.”

“People like to pick on Harry for a lot of different reasons, because he’s sort of the villain,” Vichinsky says. Ultimately, though, he predicts that Macklowe will find his buyer: “He has a great perch that is unusual.” Back when the parcel was acquired for development in the 1980s by the real-estate investor and abstract-art collector Ben Heller, neighboring property owners unsuccessfully sued to keep him from situating a house so close to the pond. It is some of those same neighbors, or their heirs, who first complained about Macklowe’s landscaping. But the neighborhood is turning over at astonishing prices. Macklowe’s former next-door neighbor, Calvin Klein, sold his pair of parcels for $85 million in 2021. A couple doors down, Macklowe’s brother Lloyd, the art dealer, sold his place for $35 million before his death last year. Harry’s location right on the pond — the very quality that got him into trouble — also makes his house precious. It would be impossible to build there today.

“You’ve got to clean that up in order to get it to where it needs to be,” Vichinsky says, greatly simplifying the expense of legalization. Macklowe has had to pay consultants, landscape designers, and lawyers, and he may soon be hiring workers to replant native grasses by hand. The process will likely cost him a million dollars or more, estimated one person involved — all just to unload the place. And then, Vichinsky says, “it doesn’t mean that the next guy won’t literally do the exact same thing.” When money wants, it tends to find a way.

See All

Source link