BBC finds huge devastation and little help for survivors in Mandalay

BBC

BBCWarning: This article contains details and images that some readers may find distressing

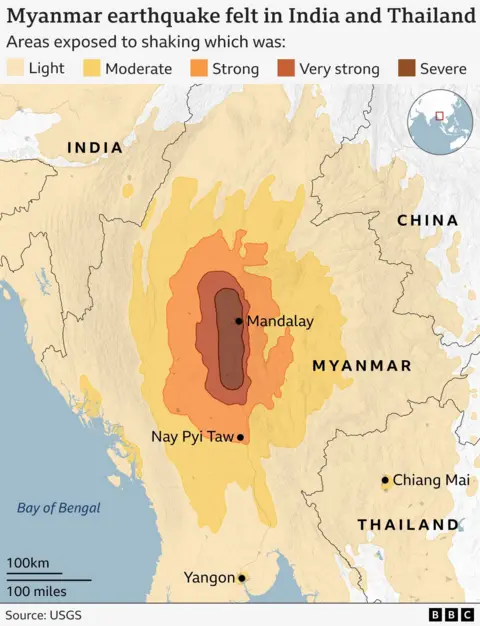

Driving into Mandalay, the massive scale of the destruction from last Friday’s earthquake revealed itself bit by bit.

In nearly every street we turned into, especially in the northern and central parts of the city, at least one building had completely collapsed, reduced to a pile of rubble. Some streets had multiple structures which had come down.

Almost every building we saw had cracks running through at least one of its walls, unsafe to step into. At the main city hospital they’re having to treat patients outdoors.

Myanmar’s military government has said it’s not allowing foreign journalists into the country after the quake, so we went in undercover. We had to operate carefully, because the country is riddled with informers and secret police who spy on their own people for the ruling military junta.

What we witnessed was a people who had very little help coming their way in the face of this massive disaster.

“I have hope that he’s alive, even if it’s a small chance,” said Nan Sin Hein, 41, who’s been waiting on the street opposite a collapsed five-storey building, day and night for five days.

Her 21 year-old-son Sai Han Pha was a construction worker, renovating the interiors of the building, which used to be a hotel and was being turned into an office space.

“If they can rescue him today, there’s a chance he’ll survive,” she says.

When the 7.7 magnitude earthquake struck, the bottom of the building sank into the ground, its top lurching at an angle over the street, looking like it could tip over at any minute.

Sai Han Pha and four other workers were trapped inside.

When we visited, rescue efforts had not even begun at the building and there was no sign they would start soon. There just isn’t enough help available on the ground – and the reason for that is the political situation in the country.

Even before the earthquake Myanmar was in turmoil – locked in a civil war that has displaced an estimated 3.5 million people. Its military has continued operations against armed insurgent groups despite the disaster.

This means that security forces are too stretched to put their full might behind relief and rescue operations. Except in some key locations, we didn’t see them in large numbers in Mandalay.

The military junta has put out a rare appeal for international aid, but its uneasy relations with many foreign countries, including the UK and the US, has meant that while these countries have pledged aid, help in the form of manpower on the ground is currently only from countries like India, China and Russia, among a few others.

And so far those rescue efforts appear to be focused on structures where masses of people are feared trapped – the high-rise Sky Villa condominium complex which was home to hundreds of people, and U Hla Thein Buddhist academy where scores of monks were taking an examination when the earthquake struck.

Neeraj Singh, who is leading the Indian disaster response team working at the Buddhist academy, said the structure had collapsed like a “pancake” – one layer on top of another.

“It’s the most difficult collapse pattern and the chances of finding survivors are very low. But we are still hopeful and trying our best,” he told the BBC.

Working under the sweltering sun, in nearly 40C, rescuers use metal drills and cutters to break the concrete slabs into smaller pieces. It’s slow and extremely demanding work. When a crane lifts up the concrete pieces, the stench of decaying bodies, already quite strong, becomes overwhelming.

The rescuers spot four to five bodies, but it still takes a couple of hours to pull the first one out.

Sitting on mats under a makeshift tent in the compound of the academy are families of the students. Their faces are weary and despondent. As soon as they hear a body has been recovered, they crowd around the ambulance it is placed in.

Others gather around a rescuer who shows them a photo of the body on his mobile phone.

Agonising moments pass as the families try to see if the dead man is a loved one.

But the body is so disfigured, the task is impossible. It is sent to a morgue where forensic tests will have to be conducted to confirm the identity.

Among the families is the father of 29-year-old U Thuzana. He has no hope that his son survived. “Knowing my son ended up like this, I’m inconsolable, I’m filled with grief,” U Hla Aung said, his face crumpling into a sob.

Many of Mandalay’s historical sites have also suffered significant damage, including the Mandalay Palace and the Maha Muni Pagoda, but we could not get in to see the extent of the damage.

Access to everything – collapse sites, victims and their families – was not easy because of the oppressive environment created by the military junta, with people often fearful of speaking to journalists.

Close to the pagoda, we saw Buddhist funeral rituals being held on the street outside a destroyed house. It was the home of U Hla Aung Khaing and his wife Daw Mamarhtay, both in their sixties.

“I lived with them but was out when the earthquake struck. That’s why I survived. Both my parents are gone in a single moment,” their son told us.

Their bodies were extricated not by trained rescuers, but by locals who used rudimentary equipment. It took two days to pull out the couple, who were found with their arms around each other.

Myanmar’s military government says 2,886 people have died so far, but so many collapse sites have still not even been reached by the authorities, that that count is unlikely to be accurate. We may never find out what the real death toll of the earthquake was.

Parks and open spaces in Mandalay have turned into makeshift camps, as have the banks of the moat that runs around the palace. All over the city we saw people laying out mats and mattresses outside their homes as evening approached, preferring to sleep outdoors.

Mandalay is a city living in terror, and with good reason. Nearly every night since Friday there have been big aftershocks. We woke up to an aftershock of magnitude 5 in the middle of the night.

But tens of thousands are sleeping outdoors because they have no home to return to.

“I don’t know what to think anymore. My heart still trembles when I think of that moment when the earthquake struck,” said Daw Khin Saw Myint, 72, who we met while she was waiting in a queue for water, with her little granddaughter by her side. “We ran out, but my house is gone. I’m living under a tree. Come and see.”

She works as a washerwoman and says her son suffers from a disability which doesn’t allow him to work.

“Where will I live now? I am in so much trouble. I’m living next to a rubbish dump. Some people have given me rice and a few clothes. We ran out in these clothes we are wearing.

“We don’t have anyone to rescue us. Please help us,” she said, tears rolling down her cheeks.

Another elderly woman chimes in, eyes tearing up, “No one has distributed food yet today. So we haven’t eaten.”

Most of the vehicles we saw pulling up to distribute supplies were small vans with limited stocks – donations from individuals or small local organisations. It’s nowhere near enough for the number of people in need, leading to a scramble to grab whatever relief is available.

Parts of Mandalay’s main hospital are also damaged, and so in an already difficult situation, rows and rows of beds are laid out in the hospital compound for patients.

Shwe Gy Thun Phyo, 14, has suffered from a brain injury, and has bloodshot eyes. She’s conscious but unresponsive. Her father tries to make her as comfortable as possible.

There were very few doctors and nurses around to cope with the demand for treatment, which means families are stepping in to do what medical staff should.

Zar Zar has a distended belly because of a serious abdominal injury. Her daughter sits behind her, holding her up, and fans her, to give her some relief from the heat.

We couldn’t spend a lot of time at the hospital for fear of being apprehended by the police or military.

As the window to find survivors of the earthquake narrows, increasingly those being brought into the hospital are the dead.

Nan Sin Hein, who is waiting outside the collapsed building where her son was trapped, was initially stoical, but she now looks like she is preparing to face what seems like the most likely outcome.

“I’m heartbroken. My son loved me and his little sisters. He struggled to support us,” she says.

“I am just hoping to see my son’s face, even if he is dead. I want to see his body. I want them to do everything they can to find his body.”

Source link