The Brooklyn Banks Reopens to Skaters, Bleak by Design

If, making your way from Chinatown to the water’s edge, say, you happen on a brick-paved expanse beneath the Brooklyn Bridge on a quiet afternoon, you might think you had stumbled on a forlorn and forgotten patch of Manhattan moated by the bridge’s ramps. Tree pits with no trees, concrete chess tables next to the roadway, a row of park benches inexplicably facing a wall of bricked-up arches — the place has a provisional look, as if it were either declining into blight or waiting to be finished. Arrive in the early morning, though, and you might come across a seniors’ Tai Chi class or a klatch of men chatting in the shade from the overpass. Later in the afternoon, a squad of skateboarders turns the plaza’s topography into an adventure zone. Spend some time crisscrossing the area, and you realize that the weedy patches scattered under and around the bridge add up to an archipelago of open spaces that are at long last coming back into their own.

Welcome to the newly reopened public space of confusing nomenclature. Skaters call it the Brooklyn Banks, although it’s in Manhattan. The city calls one section the Arches, for the vaults bordering it that once contained wine cellars. And the nonprofit organization Gotham Park, which agitated to reopen the area, calls it (yes) Gotham Park, even though it’s not technically a park. For 15 years, it’s been a no-go zone where the Department of Transportation stored equipment used in renovating the span overhead. Long before that, it was one of those leftover areas that most New Yorkers didn’t know about but skateboarders all over the world longed to visit. Rubber-bodied young people — mostly but not only male — plunged down the rolling brick slopes, rebounded off the bridge’s footings, slid along stair railings, levitated past graffiti-covered walls, skinned elbows on bacteria-rich debris, and jumped low concrete walls onto an active off-ramp where they hoped not to be crushed by a passing truck. “Only people from out of town would ever have a close call,” recalls Steve Rodriguez, one of the pioneers. “The locals knew where to start to see oncoming traffic.” Despite that reassuring distinction, that ramp was closed, because as soon as the kids figure out how to have some good life-threatening fun, a bureaucrat comes along to spoil it.

To the delight of veterans like Rodriguez and younger skaters who know the place only from vintage videos or the digital version in games like Thrasher: Skate and Destroy, the Banks are back. The reborn version, with new bricks, less broken glass, and some fresh, if sparse, plantings, is substantially unchanged but cleaner and sprucer, making it more appealing to the non-skater community. It’s been reopened in chunks, thanks to the unrelenting optimism and irrational persistence of a corps of Lower East Side and Chinatown residents led by Rodriguez and Rosa Chang. “Our chances of success were infinitesimally small,” Chang says. “It’s big, it’s a landmark, it was a construction staging area, we’re inside the Civic Center security zone — and none of us had ever worked on a park before.”

The two partners-in-park met in late 2020, when they stood on a sidewalk and peered through a chain-link fence. Rodriguez had been hanging out there starting in the mid-1980s, and he explained to Chang why skateboarders look on the Banks with such reverence. She charmed her way into meetings with city officials and, to her astonishment, found a sympathetic ear in the Adams administration. The process of prying so much as a square foot from a city agency’s clutches is generally glacially slow, but this case was relatively speedy. Chang was animated by a powerful sense of urgency — the awareness that each additional year of deliberation and delay meant another cohort of students from Murry Bergtraum High School across the street who couldn’t use the park’s hoops, another group of seniors who started spending all their time indoors, another set of neighbors who moved away before the padlocks came off the fence. Getting it done mattered more than getting it perfect. “It’s almost insane that it’s open and available,” Rodriguez says. “I’m excited for the future generations who will experience it.”

The graffiti has been scrubbed (for now).

Photo: Justin Davidson

The plaza covers three acres now; local activists are trying to make it nine altogether.

Photo: Justin Davidson

The DOT has turned over maintenance, programming, and operations to Chang’s grassroots organization, which has big plans. So far, the city has opened three acres; Chang has her eye on a total of nine, stretching from Park Row to the waterfront, and she expects the final bill to total $200 million. (“You can put in there that we desperately need support,” she remarks.) Because it’s a work in progress, the sections will be fenced off again someday, but this time around, there is plenty of space for skaters, chess players, bench sitters, and construction workers to keep out of each other’s way. When I visited the other day, it looked like a hemmed-in smear of space decorated by the pigeons roosting in the overpasses. I wondered at first whether some overworked city planner had quit in a huff and never been replaced, or some memo between departments had gone astray — how else to explain the contrast between this forbidding hardscape and the lush grounds of Brooklyn Bridge Park on the opposite shore? But it’s that rough beauty and looming infrastructure, the sense of freedom in the belly of the city — the irreducible New Yorkiness of the spot — that means so much to Rodriguez and his wheeled brethren. “Name me another plaza where you can do anything. The fact that it wasn’t designed for skateboarding but happens to be good for it — that’s huge.”

Skateboarders may love the Banks just the way they are, but the same isn’t true for every constituency. Now that a range of neighbors can start to think of the place as theirs, they will soon start to agitate for a higher-grade menu of features, like more happily placed benches, shade trees, restrooms, water fountains, flowers, pathways, and garbage cans — maybe even somewhere to buy food. There’s a reason for some of the puzzling design decisions, and it’s a dumb one: Once workers had completed the bridge repairs, they were contractually obliged to return the areas below to precisely the same condition they found them in. They didn’t have to respray the graffiti, I guess, but if some long-ago functionary decided a bench should face a wall, then the new bench was going to face the same wall. “There was no room to zhuzh it up,” says Ya-Ting Liu, the city’s chief public realm officer.

The benches, by contract, had to go back exactly where they were. Change can come later.

Photo: Justin Davidson

Now there is, though. A $50 million line item in the Transportation Department’s budget guarantees that money will be spent on Gotham Park — but it says nothing about how and when. “Right now, it’s just a vast open space. That amount presents an opportunity to begin a community visioning design process,” Liu says. It also presents some hazards: delays while different groups go into battle over whether new lampposts are overkill or insufficient, complaints from skateboarders that all the “improvements” are spoiling the authenticity and from more sedate users that the skaters are out of control. And just because the money is there doesn’t necessarily make it a priority. Administrations come and go, and Chang may soon have to convince a whole new crew at City Hall to turn desire into reality. That leaves a lot of room for never-gonna-happen skeptics to shake their heads, but Chang has earned her optimism.

The unfinished story is also a lesson in the limits of what a student of urbanism can learn just by looking. I treat the city as a mystery, challenging myself to deduce who wanted what where, what tools they used to get it, and whether they followed through. That investigative technique didn’t help under the Brooklyn Bridge, where I mistook dedication for neglect. I failed to notice a triumph of historic preservation, just because the New York that was being brought back to life here wasn’t one I had ever known. Not quite park or plaza, this collection of spaces is really a stage of sorts, what Chang calls “an invitation to play that happens to be written in brick.”

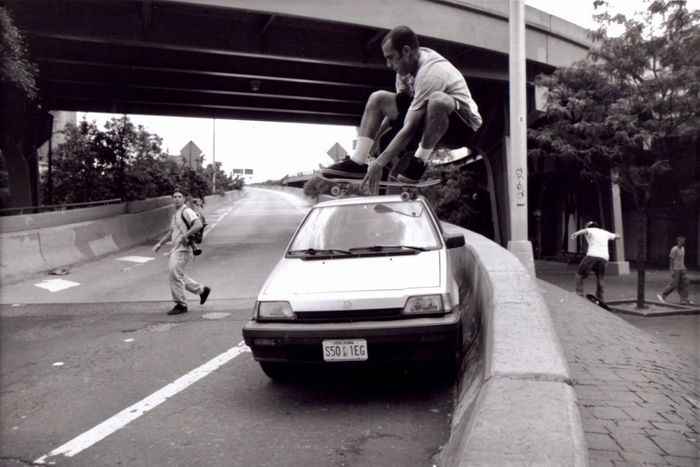

Steve Rodriguez at the Brooklyn Banks, circa 1990s.

Photo: John Engle/Courtesy Steve Rodriguez