How Mass Timber Could Revolutionize Construction in NYC

The future of architecture lies in antiquity. I don’t mean that we’re headed for another round of neoclassical nostalgia but instead that it’s time to embrace a practice so basic and immemorial that it can be made fresh again: building with timber. Prehumans carved notches into logs to fashion homes nearly half a million years ago. Ancient Greeks erected their earliest temples in wood, encoding its properties in a style they later transferred to marble. Gothic builders in England fitted out great halls with elaborately carved hammer-beam roofs. Japanese carpenters in the 17th century developed sophisticated joinery that defined a culture of construction. Those traditions represent an immense library of techniques that, for much of the last century, tastemaking designers discarded as retrograde, impractical, or unaffordable, except in certain boutique projects. Sure, we’ve had prefab log cabins, pine-lined spas, and millions of single-family houses framed in two-by-fours. But urban architects, clients, and building-code bureaucrats prefer synthetic stuff, primarily concrete and steel coated in glass.

Finally, though, wood is back in business in a versatile new form: mass timber, a sturdy, humane product engineered not from ever-scarcer old-growth hardwood trees but from much younger, softer cedar, Douglas fir, and (lately) eastern hemlock. The term covers a suite of industrial products, including glulam, a kind of megaplywood in which sheets of lumber are glued together, and cross-laminated timber, made from layering strips in perpendicular directions to maximize strength. The process combines small lengths into thick columns and huge slabs, and it opens the way to a new kind of architecture. Massiveness is its essential quality: columns like ship’s masts, beams that would do honor to a Viking hall, floor slabs that can withstand a rave. Stick-built houses turn to kindling in a fire; mass-timber structures char slowly from the outside, maintaining their integrity for hours — that is, long enough to get everyone out. They hold up well in earthquake testing, too.

Wood is inherently pleasing: complex, grained, satisfying to touch, and gratifying to smell. Mass timber is pleasing because of the qualities it can assume — delicate, powerful, supple, rugged, cozy, and polished — and its resonance with forests, shipbuilding, and even the childhood joy of simply waving a stick. It has the capacity to conjure innumerable forms of beauty. So far, though, the revolution has been quiet. I’ve been waiting years for the emergence of a bold timber architecture with designs that take advantage of the material’s expressive personality, its strength and malleability, its ability to support immense burdens or be worked in fine filigree, to form great blocks and stiff walls or else to bend like reeds. A few pioneers have focused on expressive potential. Already 15 years ago, Studio Gang bent lengths of glulam to form a kind of cellulose chicken wire for a pavilion at the Lincoln Park Zoo in Chicago. Shigeru Ban has experimented with wooden lattices, vaulting, curved planes, grids, and steel-free joinery using only pegs and dowels. Kengo Kuma & Associates uses lumber for screens, scaffolds, and panels hung on a steel-frame pavilion. ZGF roofed its new airport terminal in Portland, Oregon, in a skylit cloud of wooden curves. Still, I’ve grown impatient to see more of what the new wood is capable of — to behold buildings that must be designed with it rather than those that can be.

Prodded by the intuition that architects can do more with wood than they’ve had the opportunity to show, I asked each of four firms to come up with a speculative but realistic public project for New York, one that would take advantage of wood’s inherent warmth, elegance, and versatility. The results range in size and function: a La Guardia airport terminal by SHoP Architects, a soccer stadium in Long Island City by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, a public middle school in Red Hook by Modus Studio, and a community health clinic in Harlem by ZGF. These are not projects in the real world — but they could be. None of the firms was paid, none of the designs is completely worked out, none of these projects will be built as designed, none is going through the city’s public-approvals process, and none fully complies with the current building code. But they aren’t fantastical, either. The point of this exercise is to help visualize what New York might look like if it embraced timber with the same forward-looking enthusiasm that it once lavished on steel and reinforced concrete.

From left: MGA’s mass-timber building for Google (Sunnyvale, California) and ZGF’s Portland airport terminal. Photo: Ema Peter/MGA | Michael Green Architecture (Sunnyvale); Ema Peter (Portland).

From left: MGA’s mass-timber building for Google (Sunnyvale, California) and ZGF’s Portland airport terminal. Photo: Ema Peter/MGA | Michael Green Arc…

From left: MGA’s mass-timber building for Google (Sunnyvale, California) and ZGF’s Portland airport terminal. Photo: Ema Peter/MGA | Michael Green Architecture (Sunnyvale); Ema Peter (Portland).

From left: Kengo Kuma’s Odunpazari Modern Art Museum (in Eskişehir, Turkey) and Mesh Architectures’ Timber House (in Park Slope, Brooklyn). Photo: NAARO (Turkey); Frank Oudeman (Brooklyn).

From left: Kengo Kuma’s Odunpazari Modern Art Museum (in Eskişehir, Turkey) and Mesh Architectures’ Timber House (in Park Slope, Brooklyn). Photo: NA…

From left: Kengo Kuma’s Odunpazari Modern Art Museum (in Eskişehir, Turkey) and Mesh Architectures’ Timber House (in Park Slope, Brooklyn). Photo: NAARO (Turkey); Frank Oudeman (Brooklyn).

When those two structural materials came along in the late 19th century, they transformed the world. Steel beams arrived in the 1880s, launching an era of vertiginous skyscraper growth. The 148-foot Rand McNally Building opened in Chicago in 1890. Within a generation, the same technology permitted towers to rise nearly nine times as high: The Empire State Building, opened in 1931, reached 1,250 feet from street to tip. During the same period, steel-reinforced concrete excited Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier, who proclaimed it the essential stuff of the 20th century. Over the ensuing decades, the mixture of water, sand, cement, and rebar brought forth buildings that were tough, tall, sinuous, mass-produced, and wildly complex. Reinforced concrete laced vast distances with elevated highways, spanned valleys, dammed rivers, and protected people against bombs.

Mass timber could bring a comparable tide of formal innovation. The Skyscraper Museum’s current “Tall Timber” exhibition (which closes Saturday) highlights the global development of wooden high-rises, an ambition that’s been circulating for years. The Vancouver-based firm Michael Green Architecture, an early mass-timber evangelist, is designing a 55-story skyscraper in Milwaukee that would become the world’s tallest wooden tower. Mass timber has grown both sexy and mainstream enough that Google hired MGA to design its new Silicon Valley headquarters. These practical demonstrations matter because wood is an environmentally virtuous material that’s plentiful, familiar, easy to work with, and straightforward to produce. All you need to make more of it is dirt, sun, rain, and time. Manufacturing steel and concrete means pumping fumes into the air; wood does the opposite, stowing carbon safely out of the way until it rots or burns. Using it for construction keeps those gases out of the atmosphere even longer — for as long as the building stands. That’s the idea, at least; some experts have challenged the industry’s claims of greenness.

Excited by the ability to build without wrecking the atmosphere (as much), timber’s apostles have labored to normalize it in large-scale construction. Northern European countries have decades of experience, and several firms in the Pacific Northwest, especially MGA and Lever Architecture, have proved out the concept in project after project. The Seattle architect Susan Jones helped write mass timber into the International Building Code, which many states and municipalities (but not New York) adopt. Jones and her firm, atelierjones, also translated that legal framework into physical reality, designing Heartwood, an all-mass-timber eight-story apartment building that could be infinitely reproduced in other parts of the U.S. “It’s about getting a repetitive system into the marketplace,” she says. “People want to know what’s the ideal column spacing; they want to know how you do it. I’m just trying to build as fast as possible and create a sense of desire for something better than what’s available.”

New York has been simultaneously excited and cautious about embracing structural mass timber. The building code has gradually acknowledged its existence but still limits its height to 85 feet (about eight stories). It also prohibits exposed wood on the exterior, which means that from the street, most timber structures wind up looking pretty much like their neighbors. A few smallish apartment buildings have gone up, including Mesh Architectures’ attractively unostentatious Timber House in Park Slope. The most visible new work of wooden architecture in the city is SOM’s Moynihan Connector, the handsome truss bridge that crosses Dyer Avenue from the High Line and Hudson Yards to Manhattan West, providing an incongruously warm, quasi-rustic link between two high-gloss urban megadevelopments. You might also see it as a bridge to a timber future. In 2023, the city’s Economic Development Corporation gathered a clutch of projects into a publicly managed studio to help clients, architects, bureaucrats, and contractors all speak the same language. (Among the projects — real ones, in this case — is a recreation center at Walter Gladwin Park in the Bronx by Marvel Designs.) “We’re de-risking this new technology, making sure that regulations are clear and users understand them,” says Cecilia Kushner, the agency’s chief strategy officer. Still, a large and entrenched army of skeptics includes the Fire Department and the concrete workers union. (Supply-chain issues also get in the way: Despite the abundance of lumber from managed forests just a few hundred miles away in Maine and eastern Canada, the factories that produce CLT remain concentrated in the Pacific Northwest.) Yet the business marches on, blowing down barriers, rolling past hesitancy, and making the case for true sustainability.

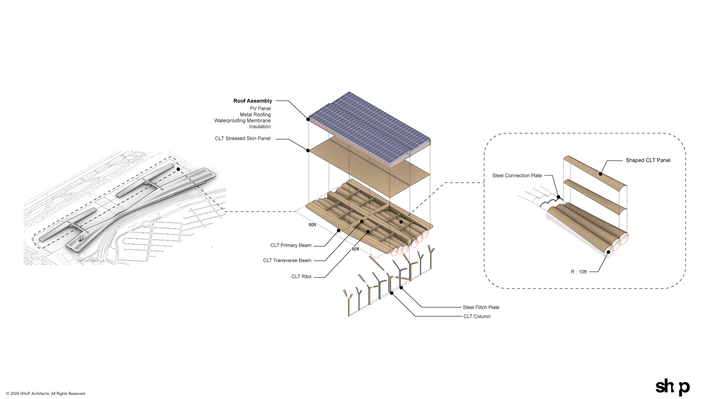

In the meantime, the architects I recruited to sprinkle the city with imaginary projects are showing how various a timber future could be. For its La Guardia terminal, SHoP focused on the combination of digital technology and mass customization that allows the finesse of carpentry to be adapted to the vast scale and industrial rhythms of contemporary construction. These days, you can design a complicated joint or a curved panel on a computer screen, send the file to a factory across the country, and have machines mill the lumber down to the smallest screw hole. No instructions are too intricate for those patient and precise robo-carpenters. Components arrive at the construction site with notches and ports for ducts already cut, and steel plates and channels preinstalled, so that putting them together is like assembling a model airplane. “We’re bringing Arts and Crafts into the 21st century,” says Christopher Sharples, one of SHoP’s co-founding principals.

Part of timber’s appeal is how un-radical it is — how even the most imaginative uses look somehow familiar. That’s partly because it’s organic but also because it’s simultaneously industrial and artisanal. Public and commercial architecture has long been dependent on a global supply chain, routines of construction, and the conventional wisdom of brokers. From the moment of a design’s inception, everyone involved has an interest in making sure it conforms to precedent and satisfies the imperatives of efficiency. The beauty of mass timber is that it can slide right into that system and transform it at the same time. It’s reliable, predictably priced, easily transported, and quickly assembled. Concrete is more dependent on the skill of pourers and the vagaries of weather. For now, building with wood costs more, but as with any other industrial product, it will benefit from economies of scale; the more popular it becomes, the cheaper it will be. That’s one reason it makes sense to incorporate it even in giant structures.

One of the essential qualities of mass timber is structure made visible. SOM challenged itself and the city to create a building large and bold enough that it couldn’t be ignored, one that would proclaim its woodiness to viewers across the East River or airline passengers on their landing glide path. In real life, New York’s first Major League Soccer stadium will go up at Willets Point, but SOM placed its imaginary alternative on the Long Island City waterfront, partly for the scenic location and also because building materials could be brought in quickly and quietly by barge. All three of the other firms grounded their designs in the theory that being surrounded by wood is good for the soul. Some research suggests that spending one’s day in an all-timber workplace can alleviate stress, or that quasi-natural environments can help people bounce back from anxiety — rather like going for a walk in actual nature. The scientific evidence for such effects is thin, but you don’t have to prove the physiopsychological benefits of a design approach to sense the difference between being enveloped in organic materials and being packaged in drywall. If you’re studying for an exam, receiving chemotherapy, or waiting out a flight delay, you might appreciate a space that at least tries to mute all that communicable agita.

These designs offer something more fundamental than a little superficial soothing or the consolations of veneer. Here, as in a genuine forest, structure and surface are the same thing. Modus proposed a version of the future Harbor School, P.S. 680, in Red Hook; SHoP, an airline terminal; and ZGF, a community health clinic at Amsterdam Avenue and West 145th Street in Harlem. The last two translate the forest metaphor into artificial groves, where columns as thick as centenarian oaks spread at the top into a canopy of abstracted branches. But the effects are different. SHoP’s team was determined to create a complete prefabricated system in which structure and finish are indistinguishable. No pouring concrete, then patching over imperfections or hiding ducts behind soffits and drywall. Instead, CLT panels, molded into conical sections, interlock to form a series of vaults. Ducts and wires tuck into the voids, and the rippled ceiling diffuses sound, creating a pleasing acoustical haze rather than an echoey hubbub. “There’s no appliqué,” William Sharples, Christopher’s brother and colleague, says. “Every piece of wood is doing a job.” ZGF and Modus gave themselves the more urbanistic task of integrating spaces devoted to healing with the neighborhood’s busy street life. In both cases, the building is a grand porch, outdoors yet protected.

Mass timber satisfies the imperatives of today’s construction industry and the demands of a fragile planet, but those rational virtues would hardly matter if it didn’t also contain deep in its grain memories of the oldest structures we know and intimations of qualities we don’t. It will take some boldness and flexibility for a steelbound city like New York to recognize that it can safely build with wood again, but then it could discover that the past holds a future of unsuspected grace.

Location: Long Island City

Architect: Skidmore, Owings & Merrill

More information here.

Illustration: SOM

SOM’s see-through dome evokes some existing structures, notably Kengo Kuma’s Japan National Stadium, but the wooden weave is unique. The execution here depends on the complex intertwining of software and logistics — the ability to calculate and obtain the precise curvature of each of over 1,500 components, preinstall the steel connections, prebuild large chunks, then ship those to the site for final assembly. The stands are a hybrid of CLT and concrete to dampen the tremors from tens of thousands of fans stomping in sync. But that base is wrapped and roofed by a basket woven from bentwood slats and covered in a translucent synthetic fabric called ETFE. The result looks at once inevitable and new, the kind of design that prompts a What?! immediately followed by Of course!

Illustration: SOM

Location: Red Hook

Architect: Modus

More information here.

Illustration: modus studio

The site sits on the edge of Coffey Park, an unlikely haven in the middle of industrial Brooklyn with its curving walkways and 126 trees. Modus, based in Arkansas, invited the park to jump Verona Street, lining up treelike square-based columns in an orderly arcade that forms a covered vestibule — a place for children to mingle out of the rain. The outdoorsy feel continues inside, where rounded columns on concrete bases support a pile of timber boxes encircling a courtyard. (An honest-to-goodness tree grows from the top floor through the roof.) The arrangement of glass-fronted classrooms feels like a set of generous cubbies or a stack of warm wooden dens. Facilities managers may object that school buildings need to be vandalismproof, and all those lovely softwood surfaces are just begging to be marred by carved obscenities. But CLT is surprisingly tough, especially when coated with a graffiti-resistant sealant, and it’s also easy to sand, patch, and recoat.

Illustration: modus studio

Is it really practical to build a wooden skyscraper?

All you have to do is look at a 300-foot redwood to realize that wood can withstand gravity and wind. The trick is to reproduce that resilience by bundling and gluing individual slats. Korb Architecture’s Ascent tower in Milwaukee is the world’s tallest timber building at 25 stories and 284 feet, but Michael Green Architecture is at work on a 55-story tower, also in Milwaukee.

What about fires?

The structural beams are so dense that they (comparably with steel or concrete) retain strength for many hours in a fire, allowing time to evacuate and call for help.

Is it expensive?

In its infancy, mass timber costs more than the equivalent in concrete — especially in the Northeast, partly because milled components often have to be imported from the Pacific Northwest or Europe.

Mass timber is made of small glued-up elements — but don’t adhesives age and grow brittle?

New glues are tough and long-lasting, but water and heat affect them, as they do steel and concrete. So mass-timber structures need to be protected from weather and designed to keep water from entering the end grain.

Are the environmental aspects of mass timber oversold?

It’s not a panacea. Adhesives contain formaldehyde, mills consume energy and produce waste wood, and trucks spew diesel fumes, so even the purest forms of construction inflict environmental cost. The benefit varies with what you’re measuring, and what you’re comparing it to, but it is significant, nearly halving the impact of certain pollutants, according to one study.

If mass timber becomes popular, won’t that lead to deforestation?

Only with bad forest management. “If you have 100 plots, you might harvest two every year while the other 98 keep growing,” says Indroneil Ganguly, a professor of environmental and forest sciences at the University of Washington. “After 50 years, you’ve completed a rotation, and you could end up with more than you started with.”

Public buildings — schools, stadiums, health centers, airports — get a lot of wear and tear. Is wood too vulnerable for those?

If zero-maintenance durability is the goal, then a world of concrete blocks is probably the best bet. But mass timber is sturdy and readily repaired, especially when coated with anti-graffiti sealants. Damage a factory-made façade panel that includes synthetic insulation and a painted metal exterior, and you’d better hope it’s still in production. If it’s wood? Sand it down and refinish.

Location: Amsterdam Avenue and West 145th Street, Harlem

Architect: ZGF

More information here.

Illustration: ZGF

The porchlike center of the building recalls the spot beneath an old oak tree that stays dry even as it begins to rain. A pair of columns carry the upper floors, whose weight is distributed over a grid of reaching branches. Large windows are framed in green terra-cotta, and the combination of color and glass accentuates the wood, which thins as it rises from trunklike column to slender trellis and from shade to skylight. Most health facilities, whether they’re research hospitals, ERs, or urgent-care storefronts, tend to retreat from public life. Walk through the automatic door in those places, and you expect to enter a medicalized habitat defined by molded plastic, stainless steel, white light, and the pervasive smell of bleach. They feel like places where you go to get sick. By contrast, ZGF invites patients and families into its multilevel forest. In an upstairs atrium, another tree reaches up to a wooden trellis and a skylight above, where it comforts the afflicted with architecture’s two most powerful tools: sunlight and beauty.

Illustration: ZGF

Location: La Guardia Airport

Architect: SHoP

More information here.

Illustration: SHoP Architects

A terminal building is an inherently long (at times it seems endless) gauntlet of concessions and waiting areas, a stress-inducing racetrack with the gate numbers counting off progress. SHoP’s design counters that linear layout by arranging curved ceiling panels crosswise to the flow, visually cross-laminating the experience of departure. It’s not something you’d consciously notice, but it does help turn the facility from a chute into a genuine place. Flight’s late? Sit back, look up, and let the ceiling’s complex crevices distract you from the anxious little screen in your hand. SHoP keeps the sense of an animate environment going overhead with a kind of inverted topography, like a cavern’s ceiling. It creates a subtle interplay of visual movement.

Tap or click to enlarge.

Illustration: SHoP Architects

Contributors: Colin Koop, Preetam Biswas, Daniel Cashen, David Miranowski, Samuel Wilson, Alice Guarisco, Sigal Shemesh, Alex Fernandez, Richardo Avelino, Ching-Che Huang (SOM); Chris Baribeau, Jason Wright, Josh Siebert, Michael Pope, Tara Bray, Sara Bartz, Chris Lankford (Modus); Kate Mann, Will Robertson, Peter Pesce, Michelle Tang, Jian Zhu (ZGF).

Source link