Legendary Designer Rose Tarlow Still Makes Her Own Rules

Photo: Courtesy of Rizzoli

Most interior-design books start to feel dated very quickly. We’ve seen coffee-table volumes — on hippie-chic bohemian design, grandmillenial maximalism, desert minimalism, and, for probably far too long, suburban farmhouse styles — come and go. That’s why it’s rare to see one of these books, especially one printed decades ago, come back. In this case, it’s A Private House, by Rose Tarlow. The Los Angeles designer, revered for her understated good taste and exclusive client list, first published the book in 2001. Modest in size and heavier on text than images, it was an unusual hybrid of memoir, decorative arts history, and practical guidebook that sold a healthy number of copies for its publisher, Clarkson Potter, before going out of print more than a decade ago. This April, the book is reappearing in a near facsimile by Rizzoli.

“When Charles Miers told me he wanted to republish it, I didn’t understand why,” says Tarlow of Rizzoli’s publisher. “I told him everybody who was going to read it has it already!” But Miers was adamant that a new generation of readers would be interested in hearing from Tarlow, who was one of only a handful of women designers working at the top of her field in the ’80s and ’90s. What made Tarlow consider his proposal, she says, was the chance to get the printing right. “I thought the colors didn’t look that great,” she says of the original volumes. “So I thought, Maybe this time it will be better!”

Tarlow, who turned 80 in January, is often referred to as a decorator’s decorator. She rarely does interviews, avoids most public events, and has never had a TV show or diffusion line. Of her fellow inductees in the Architectural Digest Hall of Fame, she’s probably had the fewest clients. “I’ve only had five or six clients over the past 30 years,” she says. “I don’t really like working for people. I like to work for myself.” Her habit of turning down jobs is legendary. (Bill and Melinda Gates are famously among the rebuffed.) The jobs she does take are for people like Oprah Winfrey, Eli Broad, and David Geffen, who don’t mind her slow, often painstaking approach. Nancy Meyers, whose films have themselves launched an untold number of home renovations, has said she often looks to Tarlow for inspiration. “Even when I’m not going to buy anything, I just like to go into her shop because she has such beautiful taste,” the director told me when I interviewed her a few years ago. “It’s an absolute treat to be in her world.” (Meyers’s own house incorporates Tarlow fabrics and furniture; she also featured a Tarlow-designed table in Something’s Gotta Give.)

The designer says she titled her book The Private House because she believes that the “intimate” act of decorating a home should be for one’s own pleasure, not for the praise of others. Her dedication to what pleases her feels remarkably coherent. “The book made a huge impression in its day,” says Miers. “Unlike a lot of books out there, it doesn’t feel like a lot of overstyled interiors or glitz. It reads almost like a poem in interior design.” On the occasion of its reissue, Tarlow spoke on the phone from her home in Bel Air about revisiting the past, her obsession with perfection, and the projects she’s still taking on.

Tarlow’s living room in Bel Air features vines that drape across the room.

Photo: Miguel Flores-Vianna

Tarlow began writing The Private House while she was teaching at UCLA’s School of Interior Design in the late ’90s, after working as an interior designer for about a decade — she had also been an antiques dealer and furniture designer a decade prior. “My students were so talented and intelligent, but I realized they knew nothing about anything before Bauhaus,” she says. So she began jotting down her advice for creating floor plans, combining colors, and picking out curtains along with anecdotes from her career and her memories of Windrift, the beachfront mansion in Deal, New Jersey, where she spent childhood summers and which she says she has “never stopped trying to replace.” She took some inspiration from a book she had loved as a student at New York’s School of Interior Design, Inside Design, by decorator Michael Greer, which she admired for its witty dictums. (One of her favorites: “Without a border on a rug, you don’t have a rug, you just have a piece of cloth.”)

Tarlow claims she never intended to tell readers what to do, but she doesn’t hold back on her opinions. “I think you have to know the rules before you break them,” she says. In fact, her book is full of rules.

“No matter how stunning or unusual it is, a carpet should not be the main focus of a room,” she declares in her chapter on floor coverings. “A deep-pile rug with a bold pattern is my least favorite option.” In a chapter on floor plans, she writes, “Too many self-important pieces in one place can keep a room from looking young and fresh, not unlike a woman wearing too much important jewelry.” (She encourages readers to create plans in fastidious detail using one-quarter-inch graph paper and an “enormous eraser.”)

Library ladders are a common feature in many of Tarlow’s projects; her own living room is no exception.

Photo: Oberto Gili

In a section on lighting, Tarlow explains how even candles can be “overdone,” begging readers: “Whatever its size, make an effort not to have your bathroom look like a waterproofed site in which to perform minor surgeries.” And pity the fool who imagines that decorating all in white is a no-fail path to chic. “There is no such thing as a colorless room just as there are no such persons as colorless people,” she writes.

Revisiting her most vehement pronouncements today, like her diatribe on flame-tipped lightbulbs (“The most unpleasant-looking bulbs imaginable are big faux-flame-tipped ones. I cringe when I see them in hallways and vestibules”), Tarlow seems a tad chastened. “Oh, you know, you can’t believe everything I say,” she says. “I always laugh when people come back to me pointing out different things I said. There’s nothing wrong with the flame-tipped bulb. I just don’t like it.”

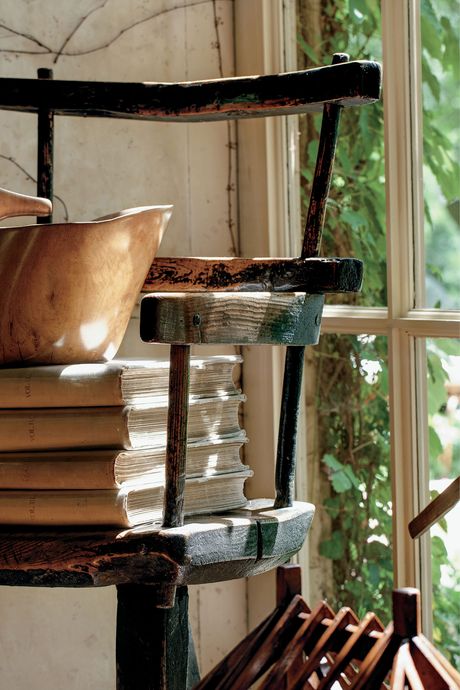

From left: Details from Tarlow’s home. Photo: Fernando Montiel Klint & Gerardo Montiel KlintPhoto: Miguel Flores-Vianna

From top: Details from Tarlow’s home. Photo: Fernando Montiel Klint & Gerardo Montiel KlintPhoto: Miguel Flores-Vianna

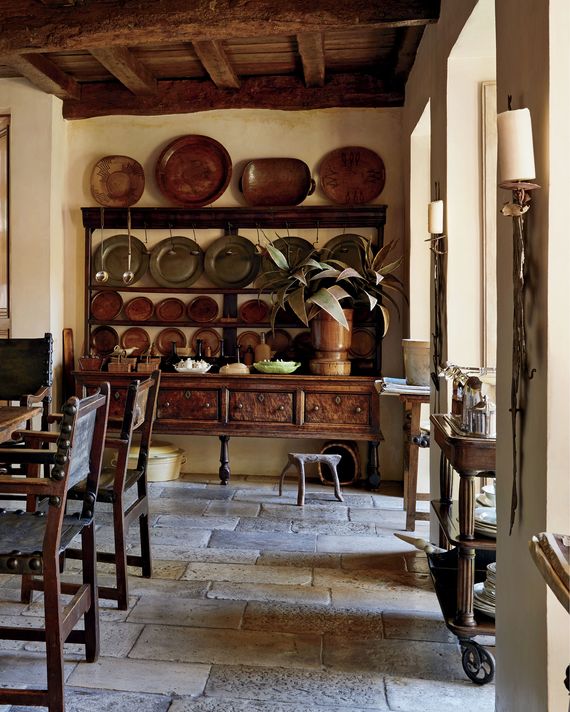

The interiors shown in The Private House — which include some of her own home, others of unnamed clients — tend toward the rustic and French with primarily wooden furniture. And although Tarlow says it’s a misconception that she dislikes contemporary furniture and bright colors (“If I were to do a new house now, it would be totally contemporary,” she says), the book’s images primarily feature antique and vintage furniture and neutral color schemes of creams, parchments, tans, beiges, and browns.

A Tarlow-designed dining room displays a collection of old English pewter chargers and antique wooden plates.

Photo: Miguel Flores-Vianna

It’s striking to see how her interiors from 23 years ago seem to embody the current design Zeitgeist. Think pale upholstery worthy of a Meyers heroine; built-in bookshelves and library ladders (TikTok “book wealth!”); dramatic displays of indoor greenery (most notably the long vines that sweep across her living room). At one point, she even describes her vision for an open kitchen with a cleverly hidden “tiny service pantry that could be used for occasional cooking and washing up when entertaining friends” — a version of the “back kitchen” phenomenon many of us only learned about a couple years ago in the New York Times.

Tarlow admits that achieving rooms that meet her standards requires not only a deep bank account but an obsessiveness bordering on mania. “I drive people I work with crazy,” she acknowledges. She’ll paint each wall in a room in a different shade of the same color to account for light reflections. (“When colors are even a speck off, I can always tell.”) She might direct where each individual stone should be laid on a floor. Most memorably, she recounts how she once commissioned an artist to hand paint wallpaper panels based on a rare 18th-century Chinese design for her family’s dining room. When the panels were finally installed, she waited until her husband and sons were asleep and then spent all night hand-aging the paper herself using 00 sandpaper and steel wool. (She couldn’t bear its “newness.”) “This is why I don’t like decorating [for clients], because I can’t stand when something looks bad, and you can’t always be there to fix it!” she says. “I still look at my own floors and I want to kill myself because they’re not the way I would do them today.”

In a 2013 story in O magazine, Oprah Winfrey recounted her bumpy first meeting with the famously blunt designer. After Winfrey gave Tarlow a home tour, the designer delivered what Winfrey describes as a “painfully honest” and “insulting” assessment. (In the piece, Winfrey goes on to say that, after she calmed down, she realized Tarlow was “absolutely right” and persuaded the designer to take her on as a client.) Tarlow acknowledges that she’s not one for sugarcoating her words. “People usually either like me a lot or they don’t,” she says. “I can be terrifying when it comes to quality. But when I say something is ‘disgusting’ or ‘horrible’ — and I know I say that all the time — I don’t mean it personally. It’s not about me being right. It’s about the piece being right.”

Tarlow transformed a client’s dining room into a pine-paneled room that also doubles as a library, complete with unusual installations.

Photo: Fernando Montiel Klint & Gerardo Montiel Klint

“I can only do one design job at a time because of the level of care I put into it. I’m still finishing what I think may be my last job. It’s very, very big — three houses for one client — that’s taken ten years,” Tarlow says. “I don’t really like working for people except for the people who I have already done houses with.” For instance, she says, “I’ve done six houses for Eli Broad.” But that started somewhat accidentally. “The only reason they became clients was because I wasn’t really looking for clients.”

But it isn’t easy to see what she’s made. Aside from her own homes, most of Tarlow’s projects are not published or, if they are, don’t reveal whose houses they are. (Many of the images in The Private House are said to be of Geffen’s homes, but Tarlow doesn’t like to discuss it.)

‘It’s not true that I don’t like color,’ says Tarlow, who designed a client’s pool house with bold green accents inspired by a trip to Ireland.

Photo: Tim Street-Porter

“One important thing you have to think about is the light. The light looks different everywhere you go. So a piece of fabric that looks white in L.A. might look gray in New York, and a kind of beige gray in London. And I think the apartment should be what the place is,” says Tarlow. “So to step out of an elevator in New York and find you’re suddenly in Morocco or Spain or the English countryside, well, I think it looks ridiculous. Of course, there are always exceptions, but this is why the only apartments I’ve ever done in New York have been very contemporary.”

These days, admits Tarlow, she is thinking about her legacy. She sold Rose Tarlow Melrose House, including her showroom, furniture, and fabrics collections, to a private-equity firm in 2008 when she briefly lost interest (“I was interested in my social life, my romances, my life,” she says) but bought it back six years later at what she calls “a very low price.” Now, she says, she enjoys going to work four days a week at her headquarters on Robertson Boulevard in West Hollywood, where she relocated the business in 2021. “I enjoy the business now more than I ever did,” she says. She travels to England and France (where she owns a home in Provence) a couple times a year to source vintage and antique furnishings, but mostly focuses on designing her own collections of furniture and fabrics. “One of the great things about being my age is that you don’t have to do anything you don’t want to do,” she says. “Now there’s no pressure — and if I want to, I can shut the door. But I like that I have some place to go and have fun every day.”

She would like the business to continue without her, she says. “I will probably work another couple years, and maybe I’ll stay longer, who knows?”

She is even working on a new book, for which — believe it or not — she plans to take the photographs herself using her iPhone. The new edition of A Private House features two of her own photos, which she shot to replace missing images from the original publication. “Just yesterday, I was walking through the living room and all of a sudden the light was streaming through the window in a way that made me see the room in a totally different way,” she says. “So I just ran over and snapped the picture.”

See All

Source link