Lincoln Center Will Finally Be Opened to the West Side

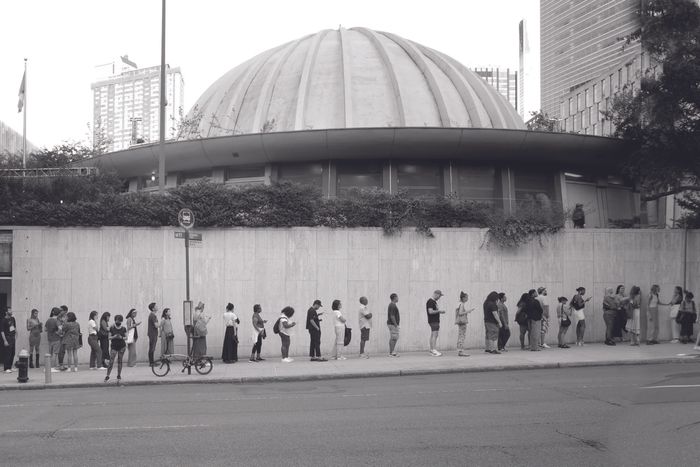

If you get to Lincoln Center from the east, you arrive wrapped in fanfare: wide stairs flanked by covered ramps, three great houses of music with luminous balconies framing a plaza, a fountain at the center, and an arcade on either side. It’s a festival of geometric grandeur. Come from the west, though, and you find yourself staring at the ass-end of a superblock, a 600-foot stretch of high white wall, interrupted only by the double orifice of a parking garage. Sure, you can enter from this side, but only at the corner of Amsterdam Avenue and West 65th Street, and only if you have the knees and lungs to climb 40 stairs without stopping for a drink along the way.

There was a powerful reason in the late 1950s to design an arts citadel like a Renaissance piazza on one side and a grim fortress on the other: prejudice. Lincoln Center’s creators knew which side of the city their audiences would come from, and it wasn’t NYCHA’s Amsterdam Houses, or the remnants of the largely Black and Puerto Rican neighborhoods that had been leveled to make way for the campus, or from the largely industrial zone closer to the waterfront. This huddle of organizations was conceived to elevate ordinary Americans through exposure to the classical performing arts—but if certain ordinary Americans desired that kind of uplift, they could damn well walk around to the front.

A kid-friendly fountain will be part of the new Damrosch Park.

Photo: Brooklyn Digital Foundry

All that is about to change… Wait, let’s not get carried away: Some of that will change, eventually. A few years ago, Lincoln Center launched a multipronged program of films, research, exhibitions, and musical works to honor the memory of San Juan Hill, an area obliterated to make way for the campus. In 2023, the institution started a scattershot campaign of asking anyone who wanted to weigh in for ideas about how to reshape its west end. Now, it’s hoping to undo the physical manifestations of an old injustice and, in essence, ungating its community.

The upshot is that the wall comes down—or at least a block-long stretch north of 62nd Street does. And when that happens, Far West Siders will be able to stroll right into a landscape designed by Walter Hood, pause in a flower garden, skirt (or sprint through) a splashpad fountain and its dancing water jets, follow a covered walkway alongside the Metropolitan Opera House, and emerge in the main plaza—no stairs or ramps required. It’ll be like undamming a stream.

“We’re changing the sociology of the space,” says Hood, who’s won a Macarthur Fellowship and a spare roomful of other awards for a practice that makes urban landscapes not just beautiful or usable, or lively, but also places of culture and memory. That is, he aspires to unwind racist planning, break down segregation, and align design with social justice. “Urban renewal”—the program of slum clearance and replacement that spawned Lincoln Center—“reinforced divisions in an already segregated society. This project attacks that typology,” Hood says.

Lincoln Center under construction (1963) and shortly after completion (1969). An entire neighborhood was swept away. From left: Photo: George Mattson/NY Daily News Archive/Getty ImagesPhoto: Charles Rotkin/Corbis/VCG/Getty Images

Lincoln Center under construction (1963) and shortly after completion (1969). An entire neighborhood was swept away. From top: Photo: George Mattson/N…

Lincoln Center under construction (1963) and shortly after completion (1969). An entire neighborhood was swept away. From top: Photo: George Mattson/NY Daily News Archive/Getty ImagesPhoto: Charles Rotkin/Corbis/VCG/Getty Images

In Lincoln Center’s main plaza in the evening, audience members’ paths form a complicated crosshatching as they move towards the Met or Geffen Hall. The regular season is winding down this month, but the Summer for the City festival is coming up, and a crew is erecting a stage near the central fountain. Over in the forgotten quadrant between the Met’s right haunch and the Koch Theater’s left, exactly three people are sitting in the geometric quiet of Damrosch Park. For them, the tranquility may be a plus (I don’t want to risk disturbing it by asking). For Lincoln Center, it’s a problem. A public park shouldn’t be a secret garden.

The area demolished for Lincoln Center, populated mostly by Puerto Ricans, was known as San Juan Hill.

Photo: Courtesy New York Parks and Recreation Department

However scarce its off-hours visitors, though, Damrosch has a fan base loyal enough to complain—to sue, even—whenever events place it out of bounds. That happens often, because the bandshell is too small, too old, and too acoustically unreliable to rely on, and so for outdoor (mostly amplified) events, workers cover it over with a temporary rig that sticks far out into the grounds, and the rest of the park gets commandeered for seating, security, and circulation. In the new plan, the bandshell disappears, and it in its place—or rather, a couple of hundred feet further from Amsterdam Avenue, just east of the new landscaping—Weiss/Manfredi will place a 2,000-seat outdoor music pavilion. The new venue (still unnamed; bidding starts now) resembles a football placed aslant the rectangular space, with the covered stage along one side and the audience arrayed along the other. That arrangement should yield one big improvement—shorter distances from seat to stage—and a host of smaller ones: Built-in everything will mean no semis parked on the surrounding streets or cables taped to the pavers. Audience members will have actual bathrooms instead of reeking Porta Potties. The acousticians at Jaffe Holden have promised that even though the stage is angled partway towards Amsterdam Avenue, amplified concerts won’t contribute to the noise level there or in the Amsterdam Houses. Count me skeptical until the first soundcheck.

Today, the bandshell (too small) turns its back on the neighborhood, and the entire campus turns a blank wall (too high) to Amsterdam Avenue. Photo: Weiss/Manfredi.

Today, the bandshell (too small) turns its back on the neighborhood, and the entire campus turns a blank wall (too high) to Amsterdam Avenue. Photo: W…

Today, the bandshell (too small) turns its back on the neighborhood, and the entire campus turns a blank wall (too high) to Amsterdam Avenue. Photo: Weiss/Manfredi.

This all looks good, or good enough, given the constraints. (One potential drawback is that the new structure will make it more difficult, maybe even impossible, to accommodate acts that carry their own venues with them, specifically the Big Apple Circus. I’m told they’re discussing the issue.) Most of that western wall along Amsterdam Avenue is the back of the Met and the Performing Arts Library, and it’s not going anywhere. The staircase at the corner of West 65th Street isn’t going to get any shorter or less steep either, but it will soon splay out and turn as it lands, making it look slightly less fearsome. The rear entrance of the Performing Arts Library will get a cladding of stainless steel draped over its travertine. Weiss and Manfredi call that an “urban curtain,” which is a wishful way of suggesting that they can make a poorly designed corner suddenly okay without getting too invasive.

The plaza’s approach to the park will look like this.

Photo: Brooklyn Digital Foundry

The travertine at the corner of the library will gain a stainless-steel cover.

Photo: Brooklyn Digital Foundry

The estimate for this whole menu of tweaks, shifts, and heavy-duty construction comes to $335 million, which buys some profound changes as well as crowd-attracting amenities (like that kid-friendly fountain). It’s also long overdue: The overhaul that Diller Scofidio + Renfro oversaw in the early 2000s didn’t touch this part of the campus. (Matthews Nielsen Landscape Architecture replaced some dead trees in 2016.) For now, Damrosch Park retains the last remnant of the geometric rigor that the modernist landscape architect Dan Kiley lavished on Lincoln Center in the 1960s. It’s a rectilinear cornucopia, with trees placed like checkers in evenly spaced square pits and a rectangular parvis receding from the incongruously swoopy concrete clamshell that backs onto Amsterdam Avenue. All that austerity seems dated to today’s designers, who prefer generous curves to tight corners. It’s hard to mourn Kiley’s precision here, given that the symmetric soul of his work disappeared two decades ago when DS + R added the elevated Illumination Lawn (a name I keep forgetting or mishearing as Elimination Lawn) to the plaza in front of the library, a tilted wave of sod on the roof of Lincoln Ristorante. I won’t miss the travertine tree boxes in Damrosch Park.

What bothers me more is the tone of self-congratulation that accompanies a project that has precious little to do with restorative justice. It’s not coincidental that this grand opening-up had to wait for several phases of gentrification to be complete. No matter how enlightened you declare yourself to be, you can’t desegregate a chunk of the city so long after almost all the people and buildings (aside from the Amsterdam Houses) have been replaced. You can’t heal the damage of displacement decades after its victims moved on, or resuscitate the profuse musical life that sprouted in the dank theaters and rickety tenements where jazz musicians like Thelonious Monk lived until their habitat was eradicated. What you can do is remember, and make only new mistakes without repeating the old ones.

Interventions like the ones that Hood and his team are cooking up have been transforming the whole city, tree pit by tree pit, bench by cafe table. Compared to a generation ago, New York is greener, cooler, and fresher (and more allergenic—all that pollen!). Strips of plantings, seating, and pedestrian-coded paving now line dozens of miles of waterfront, civilize boulevards, reclaim piers, and give neighborhoods a focal point. New York has stealthily become a better-landscaped city. That’s the more relevant historical context for the overhaul of Damrosch Park. By the time the new park-plaza-venue combo opens several years from now, the design will seem less radical or restorative than just plain normal. Lincoln Center is finally getting around to cleaning up its own bit of blight.

The future opened-up view from across Amsterdam Avenue.

Photo: Brooklyn Digital Foundry

Source link