Manhattanville Factory District: A DUMBO in Harlem?

One segment of the old Bernheimer Brewery: the multi-part Malt Building, turning the corner of West 126th Street and 127th Street.

Photo: Here and Now Agency

A vacant building is a melancholy sight, like a darkened theater or a diner sitting alone at a table set for two. The atmosphere is especially unsettled on West 127th Street in Harlem, where an office building called Malt House has grown — magically, you might think — from the husk of a 19th-century brewery. Walk in, and you’re standing in the pause between tales that have been erased and others yet to come. And because parts of it appear ruined and others gleam, it’s a freeze-frame in a film that could run in either direction; you can’t always tell the difference between incompleteness and decay.

Malt House is an artful assemblage of four late-19th- and early-20th-century structures that the architecture firm Gluck+ fused into one and topped with another handful of stories. From the street, the upper and lower parts look sharply distinct: glass above, brick below. Nobody’s tried to disguise any one element’s age by reproducing vintage windows, say. And yet, inside, old and new intertwine artfully, transforming a rough utilitarian shell that its owners beat up, punched through, and patched as their needs changed into a place that continues to tell the story of New York. At various points, the vast West Harlem complex, of which Malt House is one portion, supplied the city with beer, fixed its air conditioners, and provided its wealthy with a safe place to stash their costly winterwear in summer. The gallery Gavin Brown’s Enterprise occupied a chunk of it for five years, hoping to draw the art world to uptown turf — it was, after all, a few blocks from the Studio Museum in Harlem. It would have had a documentary-film production company, an international food corporation, a biotech start-up, and an outpost of the Columbia University Medical Center as its neighbors. And it all might have worked, had the pandemic not made a mockery of plans.

The gallery is gone now, most of the other tenants never materialized, and when construction was completed last fall, the building opened in silence. An entire little district of offices, stores, and labs crept onto the scene just as the commercial-real-estate market buckled from a seismic shift in work habits. But this isn’t just another story about the ripple effects of working from home: It’s about how crosscurrents of preservation, neighborhood history, race, public space, architecture, finance, and real estate all swirl together at the improbable oblique corner of West 126th and 127th Streets.

Once, there was beer — lots of it, produced by so many companies in so many different breweries that large swaths of the city must have had a yeasty smell. One of those sprawling facilities was the Bernheimer & Schwartz Pilsener Brewing Company, a hive of buildings, alleys, courts, and carriageways just north of 125th Street and a few blocks from the Hudson River’s ships. The brewery was run from a handsome red-brick palazzo on the corner of Amsterdam Avenue and 128th Street — at least until Prohibition got in the way. For a while, it served as cold storage for fur coats, a period memorialized even decades later in the foot-thick layer of cork insulation, the lingering smell of decaying pelts, and its current name: the Mink Building.

The long heyday of manufacturing supplied posterity with a lot of handsome and sturdy architecture that long ago outlived the purpose it was built for. Warehouses without wares, silent factories, quiet mills, power plants, garages, department stores, poorhouses — a whole catalogue of obsolete facilities that has had to be discarded or recycled, or else just left to rot. The worldwide, multi-decade project of sorting through these relics has generated its own clichés (the marriage of fresh steel and weathered brick) and more nuanced flashes of boldness. In 1989, Scott Mentzer, who trained as an architect and began, then left, a career in real-estate finance, founded a development company called Janus and set his sights on the patch of land dominated by the brewery complex. It’s taken him 35 years to collect about 20 buildings from West 126th to West 128th Street between Amsterdam Avenue and Convent Avenue, demolish a few and rescue others, driven by the idea of revivifying a neighborhood without wiping it away. The process was slow partly because the brewery was big, fragmented, and in various states of decrepitude. The site isn’t remote, but it was largely forgotten, which scared off investors and made prospective tenants cautious. And while it lacks the cultural cachet of, say, Williamsburg’s industrial waterfront, the area does matter to Harlem, which has meant navigating racial and historical sensitivities.

As part of his effort to bring a brick-and-iron-age neighborhood into the 21st century, Mentzer recently put up the Taystee Building, a shiny new glass-walled stack of labs designed for biotech researchers and quaintly named for the bakery that once occupied the site. That seemed like a smart plan. New York has been trying to turn itself into a global capital of the life sciences for years; Governor Hochul showed up to inaugurate the facility last spring. But as it turned out, that was the last busy day there. Long after dignitaries were done celebrating a new era in uptown research, the companies and institutions that conduct it are still not ready to sign a lease.

A tenant-ready, column-free floor in the Malt Building’s glass-walled addition.

The bricklike variation among the glass panes is meant to extend the masonry aesthetic.

For the main entrance, architects repurposed a sloping alleyway leading from the street to the courtyard.

The landscaped public space at the rear of the Malt Building, once the brewery yard.

Seen from the court, the new office building grows from a varied cluster of buildings that have been fused into one.

Photographs by Here and Now Agency, Brad Dickson

Malt House came next, although its metamorphosis has been slowly progressing for years. Just making the building solid and safe meant cutting away the columns’ footings and replacing them with new concrete, the engineering equivalent of changing your shoes and socks while standing on one leg at a time. Even more delicate were the choices about which bricked-up archways to open and floors to cut away, when to turn an alley into an enclosed hallway, how to bring light into a windowless warehouse, and how to make a hodgepodge of unmatched levels navigable in a wheelchair. Solve enough of these technical head-scratchers so that all the parts start working together, and you’ve got a work of sensitive architecture.

You can see the sutures between eras most clearly in one of the entrances that leads from the street, through an original archway, to a raised ground floor. To negotiate the passage between different levels, the architects installed a new steel staircase and cut away a section of the floor, flooding the basement with light from the storefront windows and opening a glimpse into the construction techniques of a century and a quarter ago. A ceiling corrugated with shallow brick vaults rests on a metal beam, which in turn sits atop a double-decker colonnade. The effect is almost acrobatic and subtly beautiful — especially because none of this was originally meant to be seen at all. A separate entrance, repurposed from what was once an alley, ramps up from the street right through to a public courtyard, where the motley backs of various buildings line up in a rogue’s gallery of varicolored brick and oddly assorted openings.

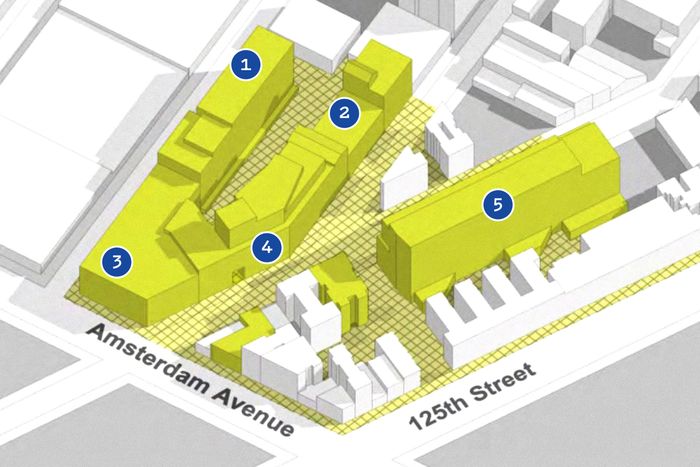

How it all fits together: (1) A future addition, as yet unbuilt. (2) The Sweets Building. (3) The Mink Building. (4) The Malt House. (5) Taystee Labs.

Graphic: Courtesy of Janus Property Company.

Look closely at the way these structures are joined, their personalities intact despite all the rejiggering, and you can only admire how much unnecessary elegance builders of that time incorporated into a plant without pretensions or preciousness. Honoring that craft today is far more time-consuming and expensive than it would be to knock the whole thing down and start again, so it’s a testament to the partnership between Janus and Gluck+ that Malt House came out both as rough and as usable as it has — and that the labor doesn’t show. The most striking component is the vertical, silolike space that Gavin Brown’s Enterprise occupied. From outside, it’s a tall, unbroken surface of bricks topped with a peaked roof, as if a child had drawn a stretched-out house and forgotten to include windows. Inside is a stack of large, unencumbered galleries topped by a dramatic double-height room. It’s a raw but grand space, illuminated from above by skylights, the sort of hall that suggests something special should take place there — a rave, a breakout art exhibition, a meeting of the clans. At first it gives the impression of having been left that way when the last of the brewery employees moved out the fermenters and vats. In fact, it took Gluck+ an immense amount of design work to make it seem like an architectural found object and at the same time render it legal and safe.

The irony is that, for this past to be preserved, preservationists had to stand aside. A dozen years ago, Mentzer cajoled neighborhood residents, the community board, and the city planning department to fold his wedge of Harlem into the river-to-river rezoning of 125th Street. Residents were skeptical of developers who came peddling expensive new apartment towers and fearful that Harlem would lose its identity as a Black haven. But Janus wasn’t offering to build housing, at least not there; instead, the company proposed reclaiming a manufacturing district as a commercial area and creating enough office space to juice the area’s economy. (You can still see a trace of the old profile in the halal butcher at the corner of Amsterdam Avenue and 126th Street: Live chickens can only be sold at an address that’s zoned for manufacturing.) The effort collided with the Landmarks Preservation Commission, which had kept the Mink Building on its to-do list for decades but never took the step of designating it as a city landmark. Michael Henry Adams was one of the loudest advocates for granting the brewery that protected status, casting the effort as a battle to save Harlem from developers’ depredations.

Mentzer complained, as property owners regularly do, that landmarking would prove too burdensome to be practical, since making even a minor change means hiring consultants and lawyers and tolerating extensive delays. That, preservationists countered, is precisely the point: Landmarking is a yellow light, meaning proceed with caution. It exists to remove personal interest and developers’ caprice from the project of protecting New York’s history, and Mentzer may have less sentimental successors who see scant value in aged architecture.

Mentzer succeeded in wresting his possessions away from Landmarks supervision by arguing that he needed leeway to inject jobs and liveliness into a three-block stretch that had seen little of either. His argument essentially came down to Trust me. The community board did, and the city acquiesced. So far, their faith has largely paid off. The Mink Building stands proud, and its neighbors have been woven into a moody and textured streetscape. Far from razing every adorable row house in sight, Mentzer is stitching his fiefdom together with public space landscaped by Terrain Work.

The new Taystee Labs life-sciences building, empty but ready for research.

Built for the brewery offices and gradually renovated to suit tenants’ needs, the 1905 Mink Building has remained un-landmarked.

Shoring up the old structures meant preserving the original columns but cutting away and replacing their footings.

Down the block from the main entrance, a new staircase from the street to the raised ground floor reveals the building’s old bones.

A skylit, double-height space at the top of a tall, windowless

warehouse lent drama to an art gallery that has since shut down.

Old and new steel beams interlock to maximize the variety of size, character, and light among the interior spaces.

Photographs by Donna Dotan Photography, Courtesy of Janus Property Company, Here and Now Agency, Courtesy of GLUCK+, Brad Dickson

Adams is unmollified. Yes, the brewery still exists, and, yes, the modern additions contrast nicely with the rough grain of brick and sandstone that still dominates those blocks. But, he says, a landmark designation would ultimately have improved the architecture and brought more harmoniousness to the streetscape, without quashing the modern additions. Janus should never have been allowed to “desecrate” (Adams’s word) the Mink Building with flush glass panes framed in dark metal panels, instead of continuing the pattern of double windows, shallow arches, and light stone mullions. “That was just some architect’s way to assert themselves on the historic fabric, like a dog marking its territory,” Adams grouses. The new Taystee Lab, designed by LevenBetts, is a far more dramatic example of the kind of interloper Adams feared: sleek and long and see-through.

So was the city right to bet on Mentzer, and was Mentzer right to bet on Manhattanville? In real estate, the answer is the same as in the koan about the zen master and the little boy: We’ll see. Janus, the god of transitions, gates, and doors, sees the whole panorama of past and future, which is a good superpower to have when your business model is patience. It must have been hard to imagine, in 1989, that these few blocks could ever become one corner of a West Harlem research triangle, with Columbia’s new Jerome Greene Science Center a five-minute walk east and CUNY’s immense Advanced Science Research Center ten minutes to the north. Even now, the district can feel far from the center of things, but then the action has moved outward in recent years, and anyway, with two subway stations a few blocks in either direction, it’s not really that far from anywhere. By 2019, Janus’s long-term gamble was paying off and had rented nearly half its space — enough to keep the lights on and lenders happy. These days, Janus has half a million pristine, attractive, and unrented square feet on its hands, and Mentzer is drawing on deep reserves of equanimity. “I’m always confident about tomorrow,” he says. “I’m just never sure when tomorrow will come.”

Source link