More Than the Frankfurt Kitchen

Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky speaks at a peace demonstration against nuclear armament in Vienna, June 1961.

Photo: Oscar Horowitz

When a flood destroyed our apartment’s kitchen some years ago, my wife and I made sure to cram as much utilitarian satisfaction as we could into its replacement, a space roughly six feet by 10 made almost luxurious by a window. With every quarter-inch accounted for, we knew where the knife block would sit, how close a wall outlet needed to be to the stove, and which pots had to fit into which drawer. We specified a cubby for oven mitts, another for cutting boards, and a slot for a folding step stool. The tinfoil drawer cleared the refrigerator handle by millimeters. Utensils, ingredients, and appliances are only ever one, two, or two and a half steps away. You’d think such a compact command center would accept only a single cook at a time, but, at the cost of a couple of collisions and one or two smashed glasses, my wife and I have developed a close-dance choreography of working together. Still, it’s the opposite of the high-end open kitchen—no island, no barstools, no guests gathering around the counter. Its conceptual ancestor is the Frankfurt kitchen, designed a century ago for the working class by the Austrian architect Margarete Schütte-Lihotsky.

MoMA has included its full-scale exemplar of Schütte-Lihotsky’s celebrated cooking pod in four separate recent shows, starting with “Counter Space: Design and the Modern Kitchen” in 2010. Now a small documentary exhibition at the Austrian Cultural Forum tries to posthumously please the designer, who died in 2000 at 102 and spent decades resenting the monopoly that one early work had on her reputation. “If I would have known that everybody would only speak about that, I wouldn’t have made that damned kitchen,” she said, probably more than once. The new show offers intriguing but frustrating glimpses of an idealistic architectural pioneer—a roving dissident and member of the anti-Nazi resistance who applied her talents to improving the lives of women and children.

The exhibition lays out the narrative across four narrow floors, illustrating it with period photographs and fragile drawings that make it all seem more remote than it really is. A short silent publicity movie from 1927 shows an elegant hausfrau with a flapper bob gliding around her kitchen stowing objects and caressing built-ins as if to show she has better things to do with her time than scrub vast floors. The history is richer than the meager visual displays let on.

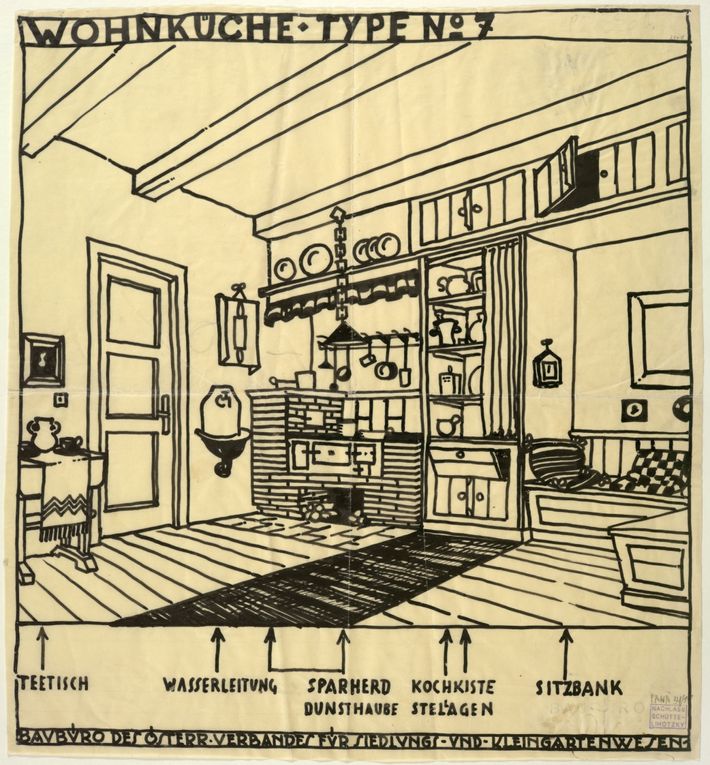

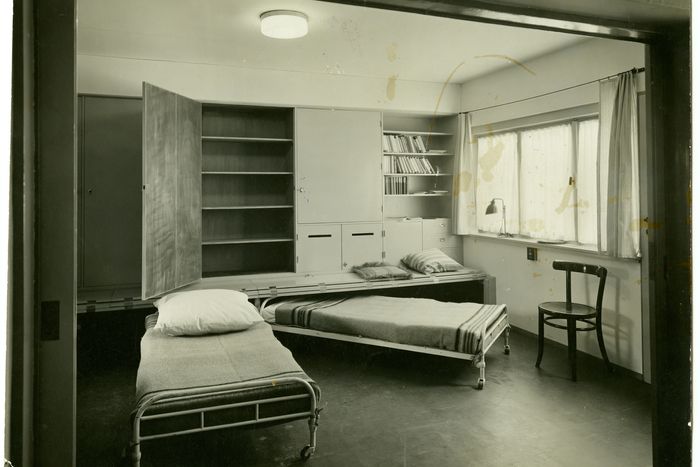

The affordable two-family duplex microapartment Schütte-Lihotsky designed for Frankfurt in 1928. Photos: Estate of MSL, © Bildrecht, Vienna, 2024, Courtesy of Collection and Archive, University of Applied Arts Vienna.

The affordable two-family duplex microapartment Schütte-Lihotsky designed for Frankfurt in 1928. Photos: Estate of MSL, © Bildrecht, Vienna, 2024, Cou…

The affordable two-family duplex microapartment Schütte-Lihotsky designed for Frankfurt in 1928. Photos: Estate of MSL, © Bildrecht, Vienna, 2024, Courtesy of Collection and Archive, University of Applied Arts Vienna.

In Vienna after World War I, with the Hapsburg empire in ruins, Schütte-Lihotsky snuck into the new wing of the Hofburg palace, a monument to Austria-Hungary’s last gasp of grandeur, A committed socialist, she set up her lonesome studio in the vacant rooms of the building where two decades later Hitler would proclaim the annexation of Austria. In 1925, the architect Ernst May, planning chief for the city of Frankfurt, invited her to join his staff. She was the only woman at the central planning authority. Those were years in which left-wing governments and progressive architects made common cause, aiming to produce public housing of high quality on an industrial scale. Later iterations—high-rise projects in the U.S., council houses in Britain, khruschevska in the Soviet Union, banlieue blocks in France—made the act of housing people decently seem like an inhuman error and created a multigenerational backlash. In the popular imagination, misguided housing policies wound up cramming the poor into squalid complexes that incubated criminal pathologies. The early years of social housing, though, show that failure was hardly foreordained. May’s group approached the topic in the possibly naïve but bracing spirit of sociological inquiry. They balanced the need for standardization with a humane attempt to understand their future tenants’ desires, an equilibrium that so many later projects got wrong.

In her work, Schütte-Lihotsky merged fervent politics and stringent rationalism, which sometimes led her into paradox. She believed that efficiency was the key to better living, especially for women, since the faster they could dispense with their chores, the more time they would have to enrich their minds. “Every thinking woman must sense how backward housekeeping has been until now and recognize this as the most serious impediment to her own development and thus also to the development of her family,” she wrote. The time had not yet come—or she was the wrong person—to point out that thinking men might have a role to play in this issue, too, or that one solution to the burdens of cleanliness was simply to care about it less. Instead, she aimed to apply Frederick Winslow Taylor’s theories of scientific management to the domestic sphere, even though in a factory setting they effectively turned workers into cogs. She seems to have missed the irony inherent in trying to make people happier by mechanizing their motions and timing every gesture.

A recent model-size reconstruction of the 1926 Frankfurt Kitchen.

Photo: Courtesy of Collection and Archive at the University of Applied Arts Vienna

Her “Core House” living room, from 1923.

Photo: Courtesy of Collection and Archive at the University of Applied Arts Vienna

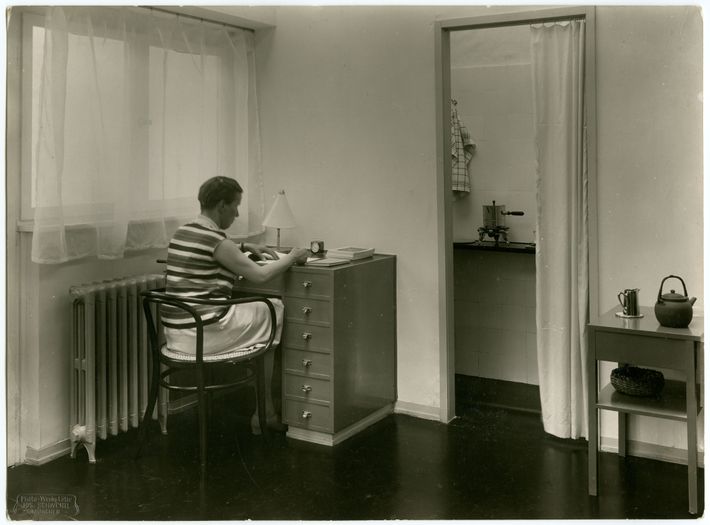

Though she merged home and family in her rhetoric, she also recognized that not all households come with spouses and children. She advocated a new category of housing: apartments designed especially for working women, who were otherwise relegated to hostels or SROs. Schütte-Lihotsky argued that, especially in the aftermath of a war that had wiped out so many men, unmarried women should not be herded into single-sex corrals. Instead, they should be offered accommodations where they could be safe and independent, without being isolated or protected to death. Her solution was the Einliegerwohnung, an affordable studio apartment (available in three different versions, at regulated rents), with its own kitchen and bathroom, built-in furniture, and a large window onto a balcony. May incorporated the design—though not the gender restriction—in his Praunheim Estate, a line of two-story single-family row houses with a setback extra unit on the roof. In designing those little apartments, Schütte-Lihotsky planned every item with a diligence that in another era would have had her working for NASA.

Schütte-Lihotzky “aimed to anticipate and shape every task. She provided a special airing cupboard for the bedding so the tenant would not be tempted to hang it from the balcony,” writes the architectural historian Susan R. Henderson. “Next to the daybed a small cupboard served as an armrest. Its upper surface folded out as a work surface and revealed a compartment divided to hold small necessities such as needles, thread, and silk; beneath this was a sewing drawer, and below that was a cupboard for mending.” There’s something stirring about the rigor with which she drew a direct line between the correct dimensions of a side table and the promise of a more egalitarian society. Since, to her, social struggle and design were indistinguishable, she also focused on another community that the architecture world had largely neglected: children. Her designs for kindergartens fostered calm routine and a sense of rational order in a world that was spinning into chaos.

Much of her life was neither calm nor routine. In 1930, she joined May in the Soviet Union, hoping to apply the lessons of Frankfurt there, which meant quietly tolerating Stalin’s mass-murderousness. She and her husband and colleague Wilhelm Schütte then moved to Istanbul and joined other expats in an anti-Nazi resistance group. There, she met Herbert Eichholzer, a good-looking young Austrian architect with impeccable left-wing credentials and a plan for redesigning the world. The two formed a strong and instant bond, though at least in her later reminiscences, the relationship was one of political sympathy rather than romantic attraction. In 1940, Eichholzer and Schütte-Lihotsky returned separately to Austria, hoping to join the resistance on the ground. Both were promptly arrested. Eichholzer was shot; she was luckier. Although the prosecution asked for the death penalty, she received a 15-year prison sentence, of which she served four.

She emerged unbowed: “The primary focus for the architect must be to fight for the kind of social structure without which his”—or her!—”architectural ideas cannot be realized,” she wrote in 1945. That argument became progressively harder to make after the war, when Europe was modernizing with Marshall Plan money, conveniently forgetting to expunge its former Nazis, and distancing itself from Moscow. During the Cold War, Austria had little interest in turning school design over to a Communist. She spent the second half of her life as an honored and highly principled holdover, perpetually rediscovered, like a conscience.

An “Apartment for a Working Woman,” shown in Munich in 1928.

Photo: Estate of MSL, © Bildrecht, Vienna, 2024, Courtesy of Collection and Archive, University of Applied Arts Vienna

We’ve moved both closer to and farther from her vision since then. For many New Yorkers, a miniature kitchen is the norm, and so are labor-saving appliances like refrigerators, dishwashers, coffee makers, and blenders that Schütte-Lihotsky wouldn’t have dared imagine might be available to the middle class. IKEA is the corporate embodiment of her desire for unfussy furnishings, cleverly designed and cheaply made. The architecture of affordable housing is also adapting to a wider range of household configurations, as tiny houses, microstudios, co-living, and multigenerational arrangements get mixed into the standard family setup. What Schütte-Lihotsky called an Einliegerwohnung is effectively a granny flat or, in more cumbersome terms, an accessory dwelling unit of the kind that California just legalized after a drawn-out battle over density.

Schütte-Lihotsky in 1927.

Photo: Courtesy of Collection and Archive at the University of Applied Arts Vienna

Frankfurt-style idealism hasn’t died out, either, even if the Cold War did its best to kill it off. University faculties, lecture series, and journals bubble with the faith that a smart enough design can guide behavior, promote peace, and ease suffering. What’s harder to recapture is the ability to muscle those ideas past developers, investors, NIMBYs, and government officials, for whom success is measured in profit or tax revenue. New public housing is a rarity, affordable apartments are usually bundled with private development, and the most architecturally ambitious governments, like China and Saudi Arabia, are also the most illiberal, more likely to dictate than to listen. And so the brittle collection of photographs, articles, and drawings at the Austrian Cultural Forum has a whiff of antiquarian nostalgia, a black-and-white reminder of a time when fiery architects had a measure of fragile and temporary power, and knew exactly what to do with it.

Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky: Pioneering Architect. Visionary Activist. is at the Austrian Cultural Forum through May 5.

Source link