Photographing Black Self-Creation in the American South

Contemporary rural places are rendered all but invisible in the American public imagination; we are a nation that celebrates big cities and suburbs. But rural towns are not only an integral part of the national fabric; they are often key to understanding our story. Hardtack, a new book from the photographer Rahim Fortune, is a case in point.

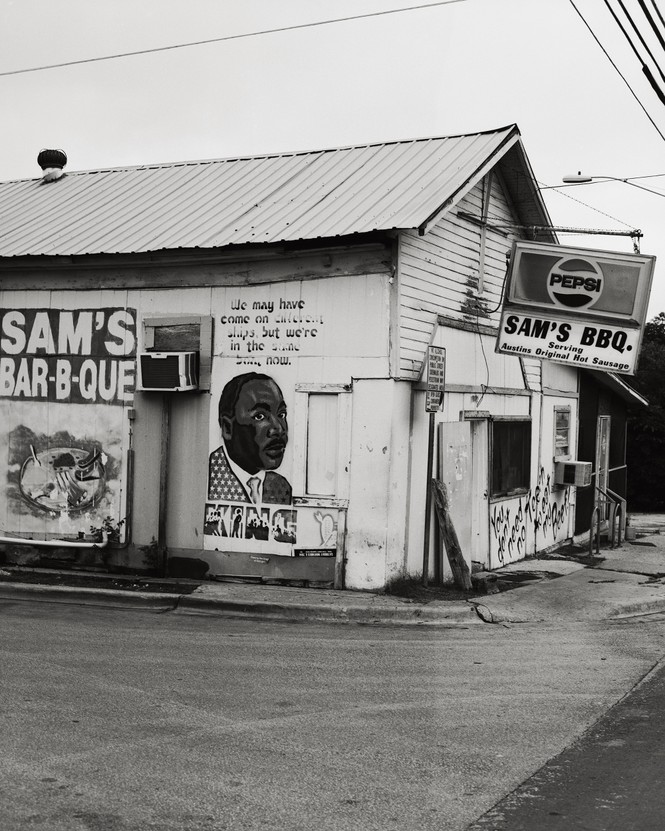

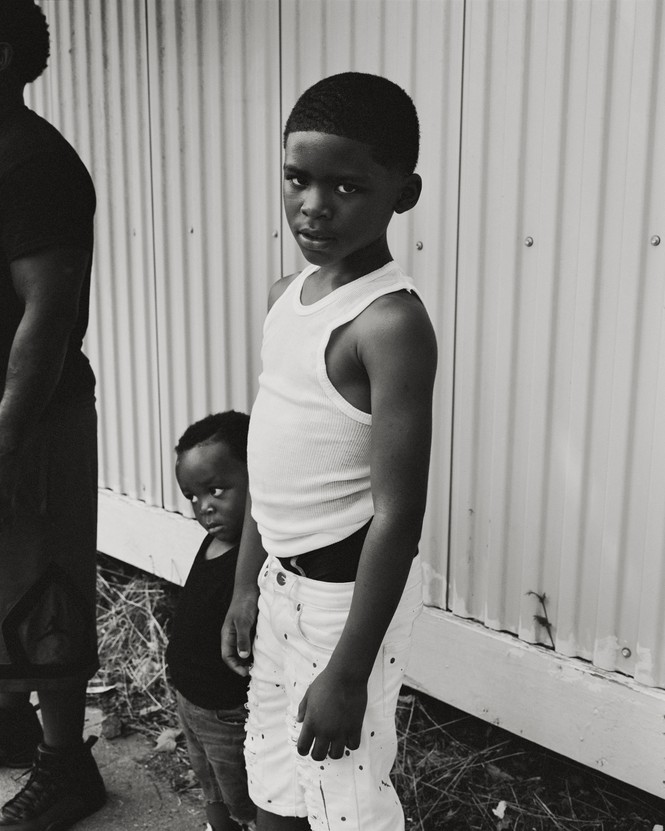

Fortune’s portraiture captures the work of Black self-creation in the thick of a humid, hard-earned history. In these images—all shot in the South, many in East Texas—the land is a character, and its people are authors. Depicting a place is always complex, but in this region, it is especially so. Some of the greatest biodiversity in the world is here, which is why people call much of southeastern Texas the “Big Thicket.” And in Ark-La-Tex (a portmanteau-crossroads, because nature doesn’t respect the lines of statecraft), the intertwined stories of the haves and the have-nots—Black, white, Indigenous, settlers and captives, driven out and ground down—are a thicket that cannot be disentangled.

Beginning after the Civil War, freedpeople founded and ran Black towns throughout the South and the Midwest. In Texas, these were aptly named “freedom colonies.” Establishing these towns provided Black people with the opportunity for self-governance and independence. The towns were also protection from the backbreaking realities of debt peonage and sharecropping. The people were no longer chattel; they were citizens. Some of these colonies flourished for a time. But they suffered, too, falling prey to common patterns—the centuries-long dispossession of small homesteads by the wealthy; the depopulation of rural places in favor of the allure of bigger cities, better-paying jobs, a life outside the reach of Jim Crow.

As King Cotton receded in prominence, the sawmills stepped in, making a big business of felling pines and hardwood trees. Then, in 1930, the East Texas Oil Field was discovered. With bread lines spreading across America, the jockeying for oil was fast and furious. Oilmen were global players in politics and business, cutting deals in international negotiations to power the world.

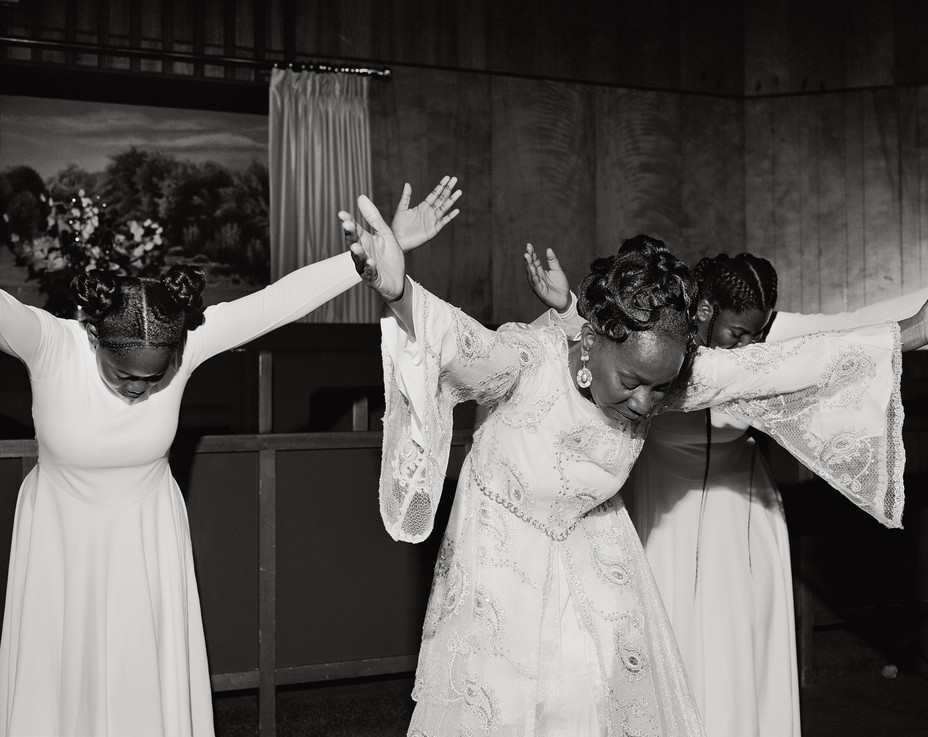

In Black churches, oil is a term of art, used to describe a vocalization that is lush with spirit; singers are told to “put some oil on it”—to anoint their voice. It might be that the hazards of the oil industry—a business of fires and explosions as well as boom and bust—facilitate an ever more passionate faith in God. Hardscrabble living will do that.

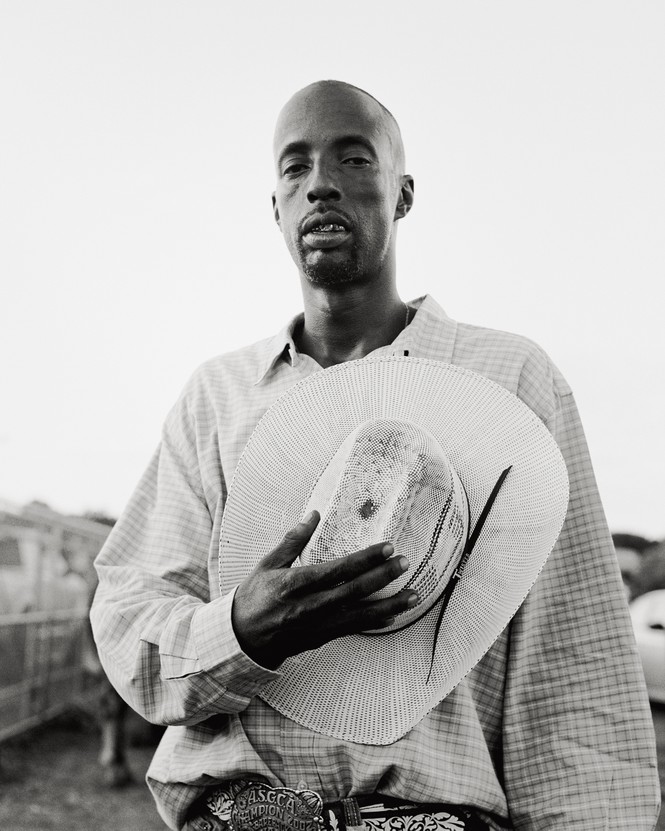

Poverty persists in East Texas today, and folks still must scuffle to stay free. In this state, you find some of the highest incarceration rates in the world. And the work has stayed hard: working cattle for milk and meat, harvesting big bunches of roses for other people’s beloveds in far-flung places, laboring over cotton and oil. Sacrifice is built into living. Residents must be prepared for tornadoes and floods that can feel biblical.

Words sit humbly alongside the clarion beauty in Fortune’s photographs. Look to see evidence of the imagination made real through human hands everywhere: in the land that is cleared; in the architecture that endures; in the quilts and elegant coiffures, the pressed and stitched shirts, the felted cowboy hats. There is a lot to be proud of. Yet the working hands raised in thanksgiving and supplication are offered in humility before God. Nature encroaches, seemingly stronger than mere muscle and faith. In person, there is so much green and blue, gold and brown—the colors of plants, water, people. Yet shot in black and white, much of what it means to be human is made crystal clear. The deliberation of a swooped bang, a diaphanous skirt cut and sewn on the bias, a thick knuckle—it is more than beauty; it is elegance in endurance.

This article is adapted from “Good Fortune,” an essay by Imani Perry that appears in Rahim Fortune’s new book, Hardtack.

Source link