PrivacyLens uses thermal imaging to turn people into stick figures

Brenda Ahearn, Michigan Engineering

Roombas can be both convenient and fun, particularly for cats who like to ride on top of the machines as they make their cleaning rounds. But the obstacle-avoidance cameras collect images of the environment—sometimes rather personal images, as was the case in 2020 when images of a young woman on the toilet captured by a Romba leaked to social media after being uploaded to a cloud server. It’s a vexing problem in this very online digital age, in which Internet-connected cameras are used in a variety of home monitoring and health applications, as well as more public-facing applications like autonomous vehicles and security cameras.

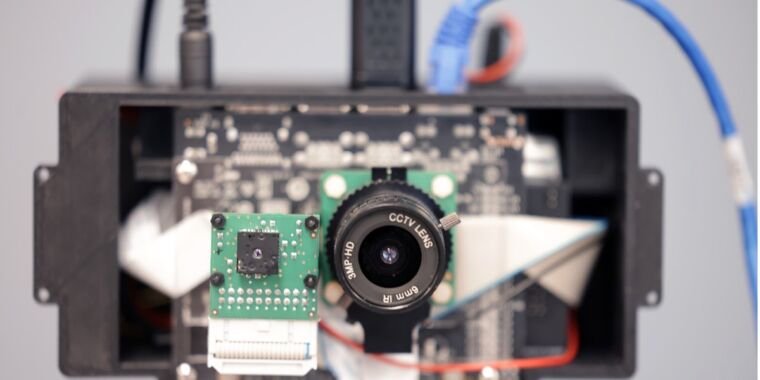

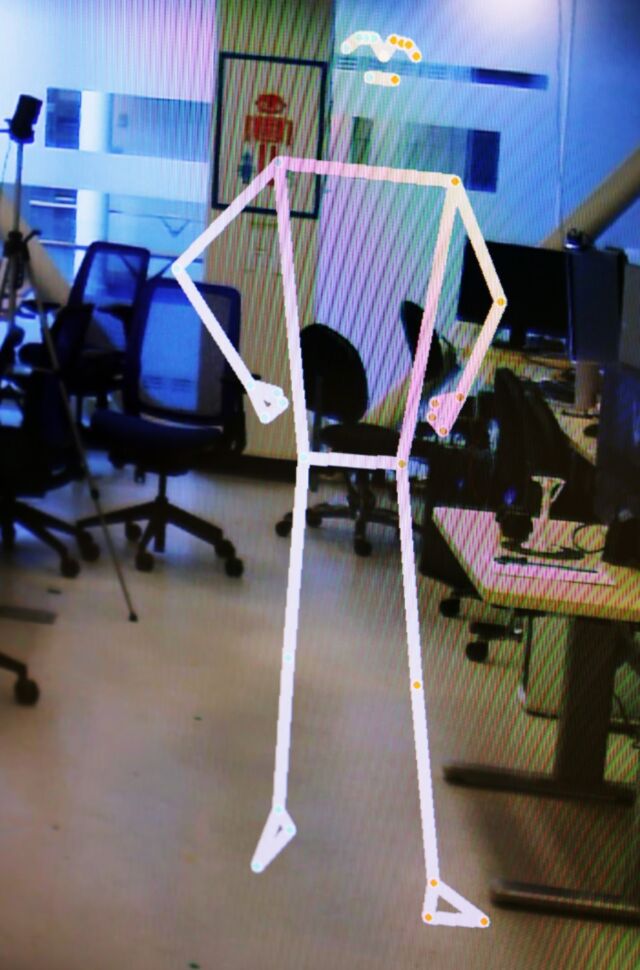

University of Michigan (UM) engineers have been developing a possible solution: PrivacyLens, a new camera that can detect people in images based on body temperature and replace their likeness with a generic stick figure. They have filed a provisional patent for the device, described in a recent paper published in the Proceedings on Privacy Enhancing Technologies Symposium, held last month.

“Most consumers do not think about what happens to the data collected by their favorite smart home devices. In most cases, raw audio, images and videos are being streamed off these devices to the manufacturers’ cloud-based servers, regardless of whether or not the data is actually needed for the end application,” said co-author Alanson Sample. “A smart device that removes personally identifiable information (PII) before sensitive data is sent to private servers will be a far safer product than what we currently have.”

The authors identified three distinct kinds of security threats associated with such devices. The Roomba incident is an example of data over-collection, outside of what the user may have knowingly agreed to be collected, along with authorized access with unauthorized sharing. (Gig workers in Venezuela tasked with labeling the data to train AI posted the revealing images to online forums.) An outside hacker constitutes unauthorized access.

Smart doorbells, for instance, have “encrypted” camera feeds, and users might thus think their privacy is secure. But such feeds can nonetheless be accessed by device manufacturer employees, data brokers, third parties, or law enforcement agencies, as well as hackers. When CCTV cameras near a subway entrance in Massachusetts captured a woman falling down an escalator in 2012, someone at the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority inexplicably shared the video footage with the press and on YouTube. It was quickly taken down, but not before many copies had been made. The footage revealed such PII as her face, hair color, and skin color.

No unnecessary surveillance

Most approaches to maintaining privacy focus on removing region of interest (ROI) details to “sanitize” personal information on true-color (RBG) images off-device. But these are vulnerable to environmental and lighting effects that can result in information leakage, according to the authors. They developed PrivacyLens to address these issues.

Brenda Ahearn, Michigan Engineering

PrivacyLens is battery-powered and combines RGB and thermal imaging with an embedded GPU that can remove PII before any data is stored or transmitted to a server—specifically face, skin color, hair color, body shape, and gender features. The thermal imaging means that people in images can be detected and “subtracted” from images based on their thermal silhouettes, replacing them with an animated stick figure. The camera can still function, but the person’s identifying features are protected. A deployment study—conducted in an office atrium, a family home, and an outdoor park—showed that PrivacyLens removed PII in 99.1 percent of images, compared to about 57.6 percent using RGB-only methods.

There are six different operational modes, depending on how much personal information the user wishes to remove. For instance, one might be fine with merely swapping facial features for a generic face (Face Swap mode) when at home in the kitchen, opting for full removal in the bedroom or bathroom (Ghost mode). That’s consistent with the findings of a small pilot study the team conducted, which also revealed a lower expectation of privacy when in public settings and hence less need for the more aggressive operational modes.

“Cameras provide rich information to monitor health. It could help track exercise habits and other activities of daily living, or call for help when an elderly person falls,” said co-author Yasha Iravantchi, a UM graduate student. “But this presents an ethical dilemma for people who would benefit from this technology. Without privacy mitigations, we present a situation where they must weigh giving up their privacy in exchange for good chronic care. This device could allow us to get valuable medical data while preserving patient privacy.” PrivacyLens could also prevent autonomous vehicles or outdoor cameras from being used for surveillance in violation of privacy laws.

DOI: Proceedings on Privacy Enhancing Technologies Symposium, 2024. 10.56553/popets-2024-0146 (About DOIs).

Source link