Public Space Has Become Earbud Space

I have a fresh item on my curmudgeonly, ever-lengthening mental catalogue titled What’s Ruining New York Now? In addition to such ordinary and eccentric scourges as rats (actual and metaphorical), sidewalk sheds, craven politicians, dog-poop neglecters, death-wish e-bikers — you get the idea — I now include earbuds. That’s not because they’re bad but because they’re everywhere. My unscientific surveys lead me to conclude that 60 to 75 percent of New Yorkers do their ambling, jogging, striding, and sitting with little plastic-wrapped electronic orbs shoved into their ears. Public space has become AirPod space.

The result is that few of the people we see in public are really there. Our bodies may be in a park or sitting in a pedestrian plaza, but our minds are tethered to some indoor environment somewhere. A walk down the street these days means eavesdropping on a disjointed series of one-way conversations, conducted at high decibels. Being alone is no obstacle to complaining about a family member’s latest outrage, reproaching a child for spending too much time in front of a screen, screaming at an errant partner, counseling a tearful friend, sending love to parents, warning colleagues that the other party in a negotiation may be about to back out, itemizing symptoms, detailing money troubles, or describing favorite foods. I collect these snippets simply by leaving my ears unoccupied. Even though we’re all being conditioned to believe that corporations and governments are monitoring our every move, people on the street shout out their most private concerns in the belief that there, at least, no one is listening.

Being so comprehensively plugged in, though, makes it almost impossible to interact with the people you see in front of you. Try stopping a passerby for directions, asking the name of a cute dog, or cracking a joke on the fly. With luck, you might get a blank sorry? smile but more likely a blank stare. Occasionally, someone will ostentatiously pull the obstruction out of one ear canal with a roll of the eyes and look at you with an expression that suggests this better be worth it.

Earbuds have become the pedestrian’s car stereo, a kind of acoustic Bubble Wrap shielding us from noise or chatter or insults and makes obsolete a once-fundamental New York experience: the casual interaction. The city’s public chatter helped Walt Whitman form his rhetorical style. He rode open-topped horse-drawn omnibuses up and down Broadway, chatting up loquacious drivers with names like Broadway Jack, Dressmaker, and Balky Bill. To him, they were America’s working-class bards, masters of the vernacular whose “declamations and escapades undoubtedly enter’d into the gestation of ‘Leaves of Grass.’” His successors must do without such yarns, and content themselves with shards of talk scattered to the breeze.

I am hardly innocent here. I recently received a pair of AirPods for my birthday (thank you!), replacing a long line of wired predecessors stretching back to Walkman days, and they are fantastic little gizmos. But I use them at home, not to pipe music or podcasts or other people’s voices into my brain when I’m out and about. The city, I feel, demands that I be alert — to my dog, to traffic, sirens, subway announcements, and the distinction between normal erratic behavior and a menacing psychotic break. Of course, this is a personal preference. Walking is a good way for me to listen to my brain — to let thoughts jostle and gel, to replay troublesome conversations, savor good memories, and let fearful fantasies play out long enough to neutralize them. Music interferes with that process. But whether that’s true for anyone else, dear reader, is between you and your psyche. Some people deploy sonic defenses as protection against harassment or sensory overload. More objectively observable is the way those who navigate New York in their own acoustic bubble relate to the city itself. A private playlist serves to distract from or glamorize the most mundane passage through physical space. We can all be Lorde in the video of “What Was That,” sashaying into the First Avenue underpass and climbing out of a sewer through a manhole, all the while enveloped in a lush pop beat. She wisely rips off her headphones before climbing on a bike. But of course that doesn’t stop the music emanating from her body — which is of course the fantasy that headphones promote: We’re not just the protagonists of our own biopic; we’re scoring it, too. Spike Jonze’s five-minute ad for AirPods doubles down on their superpower: to turn an ordinary trudge down the block into an apocalyptic drama or a summertime scene into a choreographed group freakout.

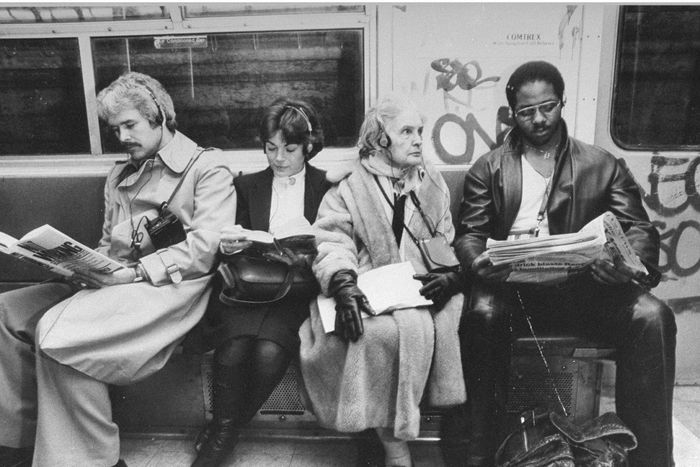

On the subway, 1981: The Sony Walkman, first imported to America in 1980, introduced the idea of personal stereo anywhere and began the gradual shutting out the city around us.

Photo: Dick Lewis/NY Daily News Archive/Getty Images

But if each of us moves about to a separate soundtrack, then is that even living in the city? Or to put the question another way: If all space is private space, then what is public space even for? Urban planners fit out plazas with a variety of seating, for instance — café tables, stools, benches, deck chairs, bleachers, corners — to accommodate a maximal range of groups and conversations. But most of those users just want to be left alone, so maybe we’re doing it all wrong. Perhaps what’s needed is an array of comfy cubicles, so that urbanites can relax outdoors in collective solitude, spared from the need to hear anything they haven’t preprogrammed themselves.

And yet I often suspect that earbuds are a form of addiction and that many people don’t actually like the isolation they permit. Lorde’s video ends in Washington Square Park, where the singer convened fans by TikTok for an impromptu concert that the police shut down for lack of a permit. When she did finally show up, that was the climax of an ultimate un-earbud moment: a crowd gathering, waiting, hoping, and dancing, all so that they could get a glimpse of the star and listen to the same music at the same time, together.

Source link