‘Saturday Night Live’ and 38 Other Reasons We Love New York

Photo: Beth Sacca for New York Magazine

There’s not much in New York that has staying power. Every other day, a new scandal outscandals whatever we were just scandalized by; every few years, a hotter, scarier downtown set emerges; the yoga studio up the block from your apartment that used to be a coffee shop has now become a hybrid drug front and yarn store. Sometimes it’s like living in whatever the opposite of Groundhog Day is, waking up each morning in a new and unfamiliar city. That makes it a little bit easier to spot the things that have stood the test of time. This year, Saturday Night Live entered its 50th season, still defiantly delirious, still doing sketches that shouldn’t resonate further than Hoboken, still helmed by the same guy who, 50 years ago, pitched what one executive called “the worst idea I’ve ever heard in my life.” Dia Art Foundation, a custodian of impossibly high-maintenance modernist art, has also been around for half a century, and so, by the way, has Eli Zabar, the Park Slope Food Coop, and the Hampton Jitney (it’s a bus). Maybe more than a city of constant turnover, we’re a city selective about what we decide to keep. Here, we’ve collected “39 Reasons to Love New York Right Now,” some of which only flared briefly, and a few that we, as a city, fought to preserve.

Reasons to Love New York 2024

See All

The first episode of NBC’s Saturday Night aired live from New York on October 11, 1975, and looked like literal trash — gray, brown, muted, somehow both dusty and wet, with sets that appeared to have been left on the sidewalk for a few days. The center stage was paved in real brick, as if the show were being performed not just in New York but on it as well. “It’s what New York was at that time and still is,” creator Lorne Michaels told Rolling Stone in 1979. “Deteriorated, run-down, and loved because of it.” Continue reading …

Photo: Mark J. Sullivan/ZUMA Press/Alamy Stock Photo

Politics is a funny business, especially in this city, where voter turnout is abysmally low and the local press corps dedicated to covering the machinations and maneuvers of the powerful has been whittled down to the size of a school-newspaper staff. Politicians can get away with a lot before the public finds out — then it can be years until the voters are able to render a judgment on their behavior.

For most of his three years in office, Mayor Eric Adams has acted like someone with little to lose. He could be out with the boys at the club until the wee hours of the morning, dine with convicted felons, and scold constituents, seemingly free of concern that he would pay a political price for any of it. He could treat his day job much the same way, hiring cronies like Tim Pearson (who is currently facing four separate sexual-harassment lawsuits) and Phil Banks (an unindicted co-conspirator in one of the biggest NYPD bribery scandals in a century) for vague and highly remunerative City Hall jobs — all while governing the city in as close an approximation of Republicanism as a Democratic mayor can (saying that migrants will destroy New York, for example, while making city streets more car and less pedestrian friendly).

Then the Southern District of New York charged Adams with bribery and soliciting illegal campaign contributions, making him the first New York City mayor to be indicted while in office. Damian Williams, the U.S. Attorney, followed that up by announcing investigations into several other members of Adams’s inner circle.

Conveniently for us, those investigations turned Adams from an avatar of backroom Brooklyn clubhouse politics into his version of a good-government guy. Gone are Pearson and Banks. Gone too are Banks’s brother, schools chief David Banks, and sister-in-law Sheena Wright, now the former first deputy mayor, who are the subjects of a separate Williams-led investigation. Also: Winnie Greco, the mayor’s director of Asian affairs, who seems to have never met a shady fundraiser she didn’t like; police commissioner Edward Caban; and nightlife coordinator Ray Martin.

In their place have emerged the kind of steady, veteran leaders who ran City Hall through previous eras — and who, had anyone else won in 2021, would have likely continued to help manage the city.

The mayor no longer proudly boasts that he has to “test the product” of the city’s club scene. A long-stalled plan to curb traffic on deadly McGuinness Boulevard in Brooklyn has been reinvigorated. The MTA began to ticket cars blocking bus lanes. The city is moving forward with plans to build 40 miles of new protected paths for pedestrians and cyclists, including turning much of Fifth Avenue in the heart of midtown over to pedestrians. After a year of complaints from residents, Adams has directed his police department to address the illegal sex trade that has set up shop on Roosevelt Avenue in Queens.

This is not how government is supposed to work. If you’re a public servant, you shouldn’t need the threat of jail time for you and everyone you’ve ever met to do your jobs. Something had to prod Adams into a more competent state. It just took a vigorous prosecution to focus this mayor’s mind.

Sadly, this moment may be brief. Williams reportedly plans to step down before Donald Trump takes office, while Adams has been all but pleading for a presidential pardon. With an election on the horizon, Adams may not last much longer around here anyway. — David Freedlander

✅ … Two Kremlin media shills, A Steve Bannon–allied Chinese billionaire,

✅ A polyamorous crypto scammer,

✅ A gold-bar-hoarding Jersey senator,

✅ And, within the same week, one of the music industry’s most notorious accused predators,

✅ Plus our nightlife-crusading, blissfully unchecked, unbalanced mayor,

✅ Along with multiple members of his administration.

Illustration: Peter Arkle

Photo: @chi4nyc/TikTok

The Real Estate Board of New York doesn’t lose very often. Last year, City Councilman Chi Ossé’s bill to end broker fees, which would simply have required whoever hires a broker to pay the fee, died without even coming to a vote. REBNY, it was reported, had coordinated with then-Councilwoman Marjorie Velázquez, chair of the Committee on Consumer and Worker Protection, to block it from coming up for a hearing. “The bill couldn’t move,” Ossé says. “It was so frustrating.” (Velázquez ended up losing her reelection bid in 2023. Ossé: “Karma is a bitch.”) But this year, when Ossé introduced it again, he chose to play a different game. On social media, his team made the fight public, forcing REBNY to respond in kind.

For once, REBNY seemed out of its depth. It attempted Instagram Reels, such as one misspelling Ossé’s name that got 136 likes. Brokers turned out in blazers and Douglas Elliman shirts at City Hall in an effort to gin up populist energy by yelling “Landlords just can’t pay fees!” (They have their margins to think about.) Ossé, meanwhile, churned out his own videos. “This guy wants your money,” he says in a viral TikTok from the spring in response to one grumbling broker. (The broker’s original video received 291 likes; Ossé’s received more than 84,000.) In another video on Instagram, with 16,000 likes, Ilana Glazer teams up with Ossé in a Broad City–esque romp around a park, encouraging people to come to a hearing for the bill. Hundreds attended.

Labor unions backed the bill, and the expanding coalition brought out some surprising characters: venture capitalist Bradley Tusk and StreetEasy. Even some brokers got onboard. In November, the legislation passed the City Council with a vetoproof majority. The day after the vote, Ossé calls to say he was “elated AF.” Meanwhile, REBNY wrote on Instagram that the fight was “far from over” and that it was preparing to take legal action. The post got 215 likes. — Clio Chang

Illustration: Pete Gamlen

Until this summer, a post-pizza-with-friends-in-the-park cleanup took one of three forms: Crack the box in half to jam it in a bin; balance it on top, leaving it to blow into the street moments later; or ditch it behind a shrub. That last option turns out to be depressingly popular among picnickers, and park staff pick up more than 100 pizza boxes on any fair-weather day in Central Park alone. Earlier this year, the Conservancy and the Parks Department introduced a solution — a pilot program of rectangular, pizza-box-specific bins installed in green spaces across the five boroughs. Each (there are ten so far) can hold several dozen boxes, and they are emptied daily or even more often. The bins’ design is open in front almost down to the ground, which leaves us mildly skeptical of their anti-rodent effectiveness, but at least we finally have an invention that embodies the Middle American image of our city: a pile of trash that nonetheless has great pizza. — Christopher Bonanos

Photo: Hannah La Follette Ryan for New York Magazine

Our most exciting cultural center opened in August as a bit among three guys sick of looking at a leaky fire hydrant at the corner of Hancock Street and Tompkins Avenue. “One of our friends said, ‘Well, what if we go and get some fish?’” says Hajj-Malik Lovick, a 48-year-old Bedford-Stuyvesant native. Lovick, with friends Je-Quan Irving and Floyd Washington, cleaned out the muck and stocked the puddle with a 50-bag of goldfish from the neighborhood pet store. The unexpected sight of the little orange carp flittering around in a glorified puddle was everywhere, a social-media must-post, a Walden surrounded by concrete at a corner known as the Bed-Stuy Aquarium.

This fall, I went to see Lovick, who was drinking green tea from a paper cup on a cold morning, surveying the puddle’s recent additions: benches, kids’ books, and the many aquarium toys that joined the fish in their open-air tank. Some neighbors concerned about the health of the goldfish had stolen some away in the night; a camera stationed over the pond discouraged any future aquatic rescues. “I’m still surprised,” Lovick says of all the visitors. “This is out of this world.”

Roey Rozen, a 26-year-old stand-up comedian from New Jersey who moved to the neighborhood three years ago, came by. “In places where you see old and new Bed-Stuy, there’s an awkward silence where both feel each other there, but the new people aren’t really saying, ‘Hey, neighbor,’” Rozen says. “The pond provides a physical space, but it’s also something to talk about.”

Bed-Stuy City Councilman Chi Ossé has stopped by for pictures. “I really like how it’s, like, these hard guys who made this really cute attraction in the neighborhood,” he says. Jadakiss came out too. “This is a Black-man-made pond,” the rapper has growled on his Instagram.

Even as the caretakers were making winter preparations in late October, the FDNY said it would “shut the hydrant off,” warning that if it froze, it would become “inoperable and dangerous.” Two firefighters came shortly thereafter to replace the leaky hydrant caps. Then the city laid concrete around the hydrant, perhaps inadvertently giving some guidance on how far one has to go to obtain city services. This was just in time for lots of people to dress up as the aquarium for Halloween. The goldfish puddle was over.

Of course, a second aquarium soon hit the neighborhood, dug into the tree well just adjacent. When and how will it end? — Matt Stieb

Illustration: Peter Arkle

From left: Photo: Sergi Reboredo/VW Pics/Universal Images Group via Getty ImagesPhoto: Courtney Cassidy

From top: Photo: Sergi Reboredo/VW Pics/Universal Images Group via Getty ImagesPhoto: Courtney Cassidy

Early one morning in May, Cortney Cassidy, a gardener on the High Line, was tending to a grove of trees near 16th Street when she noticed a pile of gray and tawny siltlike particles beneath a shrub. Not sure what to make of the pile, Cassidy asked a co-worker, who said that it was obviously cremated human remains.

As a High Line horticulturist, Cassidy occasionally comes across signs of the city’s untold heartaches. She has seen an anguished love letter scrawled on a shower curtain, the shredded pages of an erotic novel, and Paul Mescal out for a morning walk. Cremains seemed different.

Two weeks after she spotted the pile, Cassidy was in the same grove when she found another deposit of ashes. This one was much larger. Had the first pile been a smaller person? A pet? Or just a portion of one person’s remains?

New Yorkers — and maybe visitors to New York, perhaps on a pilgrimage — have, it seems, quietly decided that the High Line is a sacred final resting place.

For years, the Hindu community in Queens has used Jamaica Bay as a kind of Ganges, floating cremains into the water, much to the chagrin of park rangers; dispersing human ashes in New York’s waterways requires a permit. But anyone can scatter dust that was once a human in New York’s public parks as long as they follow a few simple rules (for instance, playgrounds and athletic fields are off-limits).

“I had no idea it was allowed!” says Richard Hayden, senior director of horticulture at the High Line. “We are touched that people feel their loved one, pet or human, wants to spend eternity with us. But, obviously, with somewhere around 7 million visitors annually, it could have a detrimental effect on our soil pH.”

At first, Cassidy tried watering the cremains into the soil. Some of the larger fragments didn’t dissolve. She has since decided that the regular appearance of human ashes is proof of the beauty and tranquillity of her portion of the High Line; she handles, roughly, the stretch from around 16th Street to 18th Street.

“I feel like this spot was chosen because it is a refuge. It’s shady on a hot day. People propose here all the time. There’s a direct view of the Statue of Liberty, and people always sit here and contemplate while looking out in that direction,” she says. “It’s very peaceful here.” — James D. Walsh

Photo: avalouiise/Instagram

James Mettham was scrolling on his phone at a PTA event one Saturday in May when he saw it: Something bad was happening at Portal. As president of Flatiron NoMad Partnership — a nonprofit Business Improvement District — he’d spent years planning the art installation, a livestream video connecting crowds here and in Dublin set into a concrete, disk-shaped sculpture in Madison Square Park. The team had high, honorably humanistic hopes, but it had prepared for trouble, keenly aware — as is anyone who has ever spent St. Patrick’s Day in New York — that our two cities share a debaucherous side.

What they were not anticipating was the troll that occurred a mere two days after Portal opened: After holding up a cell phone that said RIP POPSMOKE, a visitor on the Dublin end showed an image of smoke billowing from the World Trade Center towers on 9/11. New Yorkers gasped and booed. A day later, on the New York side, an OnlyFans model named Ava Louise (famous for licking an airplane toilet seat at the onset of COVID-19) flashed her considerable breasts to shocked Dubliners. The mayhem continued on their end, however, with at least one mooner and a person appearing to snort cocaine. Mettham went into crisis- management mode. “It was a lot of calls trying to figure out what to do,” he says. That week, his Apple Watch registered a “traumatic event” owing to his elevated heart rate.

When Portal was shut down for about a week — Mettham drops the article in front of Portal, like Burning Man or Fight Club — it was broadly taken as evidence that New York can’t have nice things. No wonder something that worked between cities in Lithuania and Poland (Benediktas Gylys, the artist behind the project, is Lithuanian) couldn’t work for us. But then Portal reopened on May 19 with limited hours. And this time it had a new mechanism that blurred the screen if anyone got too close to it as well as an on-site Portal “ambassador.” The installation successfully ran until September. This era of Portal is what Mettham hopes will be remembered. “There were so many beautiful moments — engagements, family members reconnecting,” he says. “I think New York should have nice things. We deserve that.” — Bridget Read

Photo: Stephanie Keith/Getty Images

On a cold February day, more than a thousand mourners came to St. Patrick’s Cathedral to celebrate the trans activist and actor Cecilia Gentili after her unexpected death at 52. They dressed in sequins and veils, tiny church hats and stripper shoes; they left bouquets of bright-red roses and baby’s breath in the chancel. Father Edward Dougherty joked that he hadn’t seen a crowd that well dressed since Easter Sunday. Billy Porter sang a hymn. There were eulogies; one speech affectionately called Gentili “Saint Cecilia, the mother of all whores.”

She was, in fact, a mother to a whole generation of New Yorkers, helping to expand trans-health services across the state, successfully lobbying to repeal the city’s decades-old “walking while trans” law, and co-founding the first health-care center for sex workers on the East Coast. In the days before the Mass, she was mourned on the floor of the House of Representatives and at a makeshift altar at a downtown leather party. The memorial at St. Patrick’s was organized by fellow trans activist Ceyenne Doroshow, a close friend of Gentili’s, who says she chose the location for its “pomp and circumstance. I would’ve done it in Lincoln Center if I could have.”

As an institution, St. Patrick’s is no stranger to controversy — it was the site of the funerals of Andy Warhol and Celia Cruz and the target of protests, most famously in a watershed ACT UP action in 1989. But three days after the funeral, the Archdiocese of New York denounced the service as “scandalous” and held a Mass of Reparation. Online harassment was “more awful than usual” afterward, says Doroshow, and her nonprofit lost almost $500,000 in funding. But “I would do it again,” she adds. “There’s only one Cecilia. I would only do that for Cecilia.” — Erin Schwartz

Photo: Stefan Jeremiah/AP Photo

On a bright, nippy day in late October, a council of raven-locked twinks convened in Washington Square Park to compete in a battle not of wits or strength but of resemblance to Timothée Chalamet. They were beckoned by simple flyers, about 100 printed on plain white paper, promising a $50 reward to whoever most resembled the star of Wonka, Little Women, and “dating Kylie Jenner.” Like so many Gen-Z things, it was sort of a joke but also sort of wasn’t, its seriousness evidenced by a voter turnout — including the real Chalamet — in the thousands.

There were theories about who orchestrated this, the most compelling being that it was some kind of trap set to capture the Timmy-obsessed stan account @ClubChalamet, but, in fact, it was 23-year-old creator, producer, and overall shenanigan engineer Anthony Po. Po had been making video content for nearly half his life, but since moving to the city in May, he has been able to pull off more communal stunts — like summoning sizable crowds to watch him eat a jar of cheese balls in a bright-orange balaclava under his superhero alias, Cheeseball Man, or to witness him complete a 1,000-piece puzzle only to immediately smash the whole thing. “After living here, I’m like, Holy shit,” he says. “It’s community, it’s fun, it’s lively.”

Next, Po will set up a booth under the catch line “Say Anything to 100,000 People”; participants will be able to post anything to his personal X account. He also has a couple of larger events planned for the New Year — he insists he’s done with look-alike contests now that imitators have spawned worldwide — and is currently waiting on approval from the Parks Department, albeit resentfully. “To throw a big event, it takes six months for approval and costs, like, $12,000,” he says. “Versus just showing up and getting a $500 fine. They need to figure that out.” — Rebecca Alter

Illustration: Peter Arkle

Mark Mitton doing a trick for G-Eazy at a New York Fashion Week party.

Photo: Hannah Turner-Harts//BFA.com

If, by chance, you were lucky enough to get invited to a celebrity’s 30th-birthday party this year, or perhaps a Met Gala after-party, and found yourself suddenly enraptured by a 64-year-old silver-haired magician doing card tricks, it was probably Mark Mitton. A native Canadian, Mitton has become the premier magician to the stars. His clientele is so A-list it’s not totally unusual for him to sign an NDA before working a gig. “In my heart, I’m a Canadian guy and I want to make it fun for everybody,” he says. “You want to dazzle people.” Here, in his own words, how he got this far.

I’ve made a living as a magician in New York. Isn’t that a miracle? I really don’t advertise. I do very little social media out of respect for my clients. I do a lot of high-end Wall Street events. That led to the Box; I was the house magician when it first opened, and that’s when I started working at celebrity events. I stole Sting’s watch there once. You know Jay-Z and Beyoncé? I performed for them. And John Mayer! John Mayer brought me on a cruise to work for his musician friends. I did an after-party at the Grand Prix in Monaco. That was pretty crazy. I did I. M. Pei’s 90th birthday at the Colony Club. Also the opening of the Miu Miu store in Shanghai. It’s always an honor to work with Mrs. Prada. At the Met Gala this year, I performed for Usher’s friends at his after-party. It was a real honor. I did a trick for Ne-Yo and Erykah Badu. Dwyane Wade and Gabrielle Union were so sweet. Willy Chavarria? He was all decked up. Janelle Monáe was so kind. Usher introduced us personally.

I just did the after-party for Duran Duran’s Halloween show. I was supposed to do the after-party for the UFC event at Madison Square Garden, but it never happened because Trump and Musk showed up, so everything got derailed. I performed for G-Eazy at a fashion dinner. There are some other jobs, but they’re really unmentionable. Like for [redacted billionaire]. It was an incredibly intimate event with 60 of her closest friends. It was beautifully done. I did a 15-minute show in honor of her. Her uncle invented the [redacted]. — As told to Brock Colyar

Photo: Citizen Weiner

Days before the 2021 primary election, the New York Post broke a bombshell story about a City Council race on the Upper West Side. The 26-year-old candidate Zack Weiner had been videotaped in a BDSM dungeon, ball-gagged and nipple-clamped, and the campaign was copping to the leaked footage before its opponents could weaponize it. “I am a proud BDSMer. I like BDSM activity,” Weiner told the Post, though he admitted he worried what his old rabbi at the Ramaz School would think: “That one’s a concern.”

Weiner went worldwide: Stephen Colbert and Seth Meyers found the story irresistible. Vice published a concerned piece suggesting Weiner was the victim of revenge porn, and both OnlyFans and Twitter banned accounts linked to the video.

To the extent they were known at all, Weiner’s central campaign planks — filling vacant storefronts and increasing “financial literacy” — were forgotten. Two ball-gagged allies showed up at Weiner’s final campaign rally outside the subway station at 72nd and Broadway, and Weiner finished sixth out of six candidates, exceeding expectations with 2.4 percent of the vote.

This year, he revealed the campaign itself had been a stunt, filmed from the start and designed for the screen. The resulting movie, Citizen Weiner, is a political documentary so amusing and original it’s difficult to categorize. The line between real and fake is blurred to the point of disorientation. As in life, candidate Zack Weiner was a Bard College dropout who lived with his mother on West 76th Street and appeared to rarely leave the neighborhood.

Weiner; the actor Joe Gallagher, who plays his campaign manager; and the film’s director, Daniel Robbins, met me recently at the Metro Diner at Broadway and 100th. Weiner and Robbins became friends at Ramaz, the Modern Orthodox private school on the Upper East Side. They also co-wrote Bad Shabbos, a comedy starring Kyra Sedgwick, which won this year’s Audience Award at the Tribeca Film Festival.

Bummed out by a breakup and the presidential-primary race of 2019, Weiner decided to fuse his angst with a script idea about a politician who benefits from a scandal.

The film’s biggest expense was a $12,000 camera; they had to cough up another $5,000 for an election lawyer, a profane oddball who worked for Maya Wiley’s mayoral campaign. The race’s winner, the UWS fixture and then–Manhattan Borough president Gale Brewer, serves unknowingly as the film’s Establishment villain. “Gale Brewer’s name is on city signs if you’re coming in,” Weiner says at one point, mulling her advantages. “But that’s if you’re coming in. Which means you don’t live here.”

The movie’s deadpan sensibility is balanced by Weiner’s and Gallagher’s good-guy magnetism and their sometimes-earnest interest in local politics. “We became obsessed with Alvin Ailey. They get so much of the discretionary budget of the district,” Weiner says. “We like dancing, but come on,” Gallagher says.

The movie’s third act turns on the sex tape. Gallagher created the fake OnlyFans account, then a bogus Twitter account, where he first posted the footage. Nobody picked it up — until Gallagher, ingeniously, just sent it to the Post.

As the story blows up, the film showcases the scene-stealing talent of Weiner’s mother, Cherie Vogelstein, a former playwright. “People console me all the time that I have a freak for a son,” she says after the scandal breaks.

“Why do I enjoy BDSM? For me, personally, I’m interested in one thing. And it’s women telling me what to do,” Weiner says on-camera. “I think it’s just part and parcel with my desire to be a public servant.”

Weiner isn’t ruling out future political runs, nor is he ruling out more made-up scandals to propel them. “The percentage that I won is almost exactly the percentage that Hitler won in his first election,” Weiner points out. Gallagher, apparently still in character, adds, “Now we just need to coalesce the different factions.”

The film premiered at the Village East by Angelika in October. Drawing on this newfound political experience, Robbins has advice for the city’s scandal-plagued mayor: “Stay in power. Resigning doesn’t solve it. It just makes you irrelevant. You lose all your leverage.” — Simon van Zuylen-Wood

From left: An untitled Dan Flavin installation at Grand Central Terminal, 1976–77. Photo: © 2024 Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Courtesy Dia Art Foundation Archives, Beacon, New York/ “The Broken Kilometer,” by Walter De Maria, 1979. Photo: Jon Abbott/© The Estate of Walter De Maria/Courtesy Dia Art Foundation Archives, Beacon, New York/

From top: An untitled Dan Flavin installation at Grand Central Terminal, 1976–77. Photo: © 2024 Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/…

From top: An untitled Dan Flavin installation at Grand Central Terminal, 1976–77. Photo: © 2024 Stephen Flavin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Courtesy Dia Art Foundation Archives, Beacon, New York/ “The Broken Kilometer,” by Walter De Maria, 1979. Photo: Jon Abbott/© The Estate of Walter De Maria/Courtesy Dia Art Foundation Archives, Beacon, New York/

Back in 1974, when it wasn’t entirely clear what an emptying-out New York City might still be useful for, some people thought it might best be used for something useless. These were the artists, and their self-styled patrons, who saw an opportunity in this growing obsolescence to make grand aesthetic gestures on the cheap. Two very different nonprofits established to take advantage of that dereliction still thrive a half-century later: the Dia Art Foundation and Creative Time.

Creative Time sought to make spectacle out of overlooked urban spaces. That meant allowing a menagerie of sculptures — called “Art on the Beach” — to pop up on the empty landfill created by the construction of the World Trade Center. It helped throw the “Sanitation Celebrations,” which included artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles’s mirror-clad garbage truck. The organization also was behind Rashid Johnson’s “Red Stage” on Astor Place in 2021, which encouraged people to say their piece, and grabbed a minute of every hour on a big screen in Times Square, and helped AIDS activist group Gran Fury distribute its work on city buses. After 9/11, the group sponsored “Tribute in Light” at the site of the former World Trade Center, perhaps one of the best-known public-art projects in the world.

From left: “tropos,” by Ann Hamilton, 1993. Photo: Thibault Jeanson/© Ann Hamilton/Courtesy Dia Art Foundation Archives, Beacon, New York“Double Torqued Ellipse,” Richard Serra, 1997. Photo: Dirk Reinartz/© 2024 Richard Serra/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Courtesy Dia Art Foundation, New York

From top: “tropos,” by Ann Hamilton, 1993. Photo: Thibault Jeanson/© Ann Hamilton/Courtesy Dia Art Foundation Archives, Beacon, New York“Double Torque…

From top: “tropos,” by Ann Hamilton, 1993. Photo: Thibault Jeanson/© Ann Hamilton/Courtesy Dia Art Foundation Archives, Beacon, New York“Double Torqued Ellipse,” Richard Serra, 1997. Photo: Dirk Reinartz/© 2024 Richard Serra/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Courtesy Dia Art Foundation, New York

While Creative Time sought to confront and delight and comfort, Dia, also founded in 1974, was deliberately obscurantist — essentially a rarefied club for aesthetes underwritten by Philippa de Menil, now Fariha Fatima al-Jerrahi, an oil heiress with a European aristo pedigree and the idea that she was a modern-day Medici. Dia supported mostly minimalist artists in their projects, which were tucked into various corners of the city as well as around the country — creating essentially one-man museums (they were then pretty much all by men) with the intention of keeping them going as almost holy sites suitable for pilgrimage in perpetuity. With installations that included Walter De Maria’s “Earth Room” — yes, it’s a room full of dirt you can still visit in Soho — Dia never sought out ways to please the crowd, or be understood by it, or maybe even be noticed by it.

Dia is best known these days for its date-excursion-appropriate, Instagram-friendly museum in a former Nabisco facility in Beacon. Jessica Morgan, who has been Dia’s director since 2015, which saw the reopening of a space in Chelsea, says the through-line is not only that “the art should dominate the museum and not the museum art,” as the planning documents put it, but that everything the artists do should stick around for a while. “We work with this very extended temporality and still have the people come without ‘getting on the bandwagon’ to speed that up,” she says. “The shortest project we do is a year.” While Creative Time plays in the disposable and the ephemeral, even just in light itself, Dia’s work, at least in theory, is supposed to last forever. — Carl Swanson

From left: “If You Lived Here …,” organized by Martha Rosler, 77 Wooster Street, New York, 1989. Photo: Oren Slor/© Martha Rosler/Courtesy Dia Art Foundation Archives, Beacon, New York/ “Rat-King,” by Katharina Fritsch, 1993. Photo: Bill Jacobson Studio/© 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/Courtesy Dia Art Foundation Archives, Beacon, New York

From top: “If You Lived Here …,” organized by Martha Rosler, 77 Wooster Street, New York, 1989. Photo: Oren Slor/© Martha Rosler/Courtesy Dia Art Foun…

From top: “If You Lived Here …,” organized by Martha Rosler, 77 Wooster Street, New York, 1989. Photo: Oren Slor/© Martha Rosler/Courtesy Dia Art Foundation Archives, Beacon, New York/ “Rat-King,” by Katharina Fritsch, 1993. Photo: Bill Jacobson Studio/© 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/Courtesy Dia Art Foundation Archives, Beacon, New York

From left: Trisha Brown Dance Company in performance at Dia Beacon in 2010. Photo: Stephanie Berger/Courtesy Dia Art Foundation, New York“Bass,” Steve McQueen, 2024, at Dia Beacon. Photo: Bill Jacobson Studio/Courtesy Dia Art Foundation, New York/

From top: Trisha Brown Dance Company in performance at Dia Beacon in 2010. Photo: Stephanie Berger/Courtesy Dia Art Foundation, New York“Bass,” Steve …

From top: Trisha Brown Dance Company in performance at Dia Beacon in 2010. Photo: Stephanie Berger/Courtesy Dia Art Foundation, New York“Bass,” Steve McQueen, 2024, at Dia Beacon. Photo: Bill Jacobson Studio/Courtesy Dia Art Foundation, New York/

Photo: Harry How/Getty Images

Aaron Judge is the larger-than-life superstar, but moving forward, Juan Soto’s the player the Yankees can’t afford to lose, an on-base machine with a combative but still joyous personality that fits in perfectly in pinstripes. The only problem: He’s quite famously a free agent, and he made a point, within minutes of the last out of the World Series, of letting everyone know it.

Photo: Michael Owens/MLB Photos

2023 was the dourest year yet for the Mets with all their historical ineptness seemingly encapsulated in one season: a bloated payroll resulting in overhyped expectations and comical underperformance. Then Francisco Lindor — a man booed by Mets fans in his very first week in Flushing — made this team, and in many ways this city, his. Lindor had the best year of his career in 2024, but it was more than that: The Mets — and, amazingly, their fans — took on his jubilant nature. There’s a reason he’s known as Mr. Smile.

Photo: Elsa/Getty Images

No city team in the five major professional sports had won a championship in more than a decade. But when Sabrina Ionescu, the Liberty’s star point guard, hit her jaw-dropping, text-all-your-friends-immediately 28-foot dagger to win game three of the Finals against Minnesota, you knew it was our time. Forget the new Kobe — she’s the new Willis Reed.

Photo: Nathaniel S. Butler/NBAE

Everything New York City sports fans want in their athletes, Jalen Brunson delivered. He was undervalued (a second-round draft pick), he is small but resilient, he outhustles and outscraps everyone, and, most important, he wins. Brunson has changed everything about the Knicks, even the way they think about themselves — how often do you even hear the name Jim Dolan anymore? — Will Leitch

Photo: Erick W. Rasco/Sports Illustrated via Getty Ima

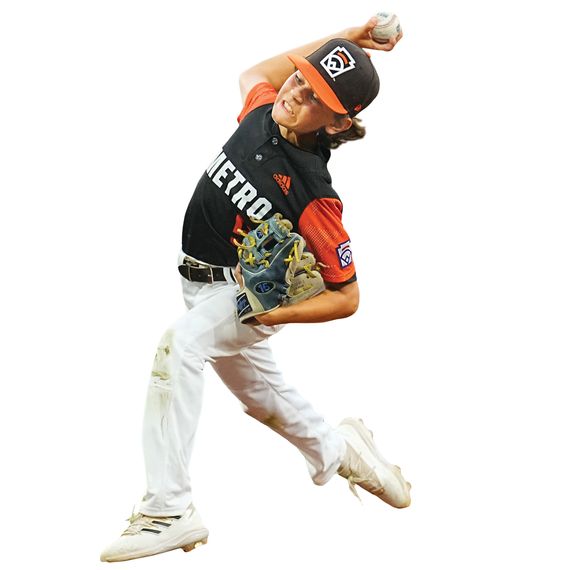

In a year of showstopping New York baseball, one may forget that we actually had two teams make World Series appearances: the Yankees and Staten Island’s South Shore Little League All-Stars. (It had been 15 years since either reached their respective championship series.) Many of this year’s All-Stars, made up mostly of 11- and 12-year-olds, have played together for years in Staten Island with the series always in their sights. During the summer, they hardly took more than a day off. “It was work over not only this season but last season and the season before,” says manager Bob Laterza. “Those kids were on a mission.” Although they ultimately lost to Florida, they finished their season with a 19-4 record. The highlight, says Laterza, was their come-from-behind 6-5 win against Connecticut in the regional semifinal. Peter Giaccio, 12 years old, hit the winning run and was “so ecstatic” he just kept running, even as his teammates tried to swarm him: “The whole team couldn’t even get within ten feet of him.” — Jeremy Rellosa

Photo: Elsa/Getty Images

Joe Tsai and Clara Wu Tsai, the married co-owners of the Brooklyn Nets and Barclays Center, bought the New York Liberty from James Dolan in early 2019, installed Jonathan Kolb as general manager, and brought the team back from its exile in Westchester. Together, they made a pact to overhaul the franchise’s basketball and business alike. “That’s where we revamped our entire marketing and identity,” Keia Clarke, the team’s CEO, says. “We broke it down all the way to the studs.”

The Liberty selected Sabrina Ionescu with the No. 1 pick in the 2020 draft and made the move to Barclays in 2021. Sandy Brondello came on as head coach in 2022, and Barclays hosted its first WNBA playoff game in front of just 7,800 people. The crowd got loud, and Clarke felt hair stand up on her arm; she looked at a colleague and mouthed, “We’re going to do it.”

In 2023, Kolb and the New York front office pulled off what history may regard as the greatest series of signings in WNBA history, including of All-Star center Jonquel Jones. The generational talent Breanna Stewart and veteran point guard Courtney Vandersloot took pay cuts so that the stacked team could meet the league’s salary cap. There is also the attraction of the ownership standard set by the Tsais: perks include state-of-the-art locker rooms and practice facilities, catering, and private flights (which incurred a $500,000 fine for violating a now-abolished league rule).

This year, the team won the franchise’s first-ever WNBA championship — and New York’s first pro-basketball title since 1976.

The business has grown apace. Ellie the Elephant, the lovably cheeky mascot, has earned a following so cultish that fans could buy replicas of her braid at the team store. It used to be that going to a Liberty game just meant you were probably a lesbian who happened to be free on a Saturday afternoon, but seats are harder to come by now: Average attendance jumped more than 60 percent this year. Even so, as the season roared to a climax, being a fan felt special, a shared secret and ritual, for a team that now happens to be the best in the world. Turns out it was all part of the plan.

“I credit our fan base for what it feels like at a New York Liberty game, but make no mistake: We are prompting them,” Clarke says. “There’s so much intentionality that goes into the run of show. There’s a text chain that’s almost like a vibe check. Like, ‘Have we done the Ellie Wave? Is the Ellie Stomp up next?’”

There is probably no better measure of the team’s mainstreaming than its ability to get an entire arena of New Yorkers to pretend its freebie tea towels are elephant trunks. “We utilize every single resource and every single lever,” Clarke says, “that we could ever pull — that we can continue to pull, I should say; it’s not done — to ensure that the entertainment quality in this building is at its best.” — Emma Carmichael

Photo: Matthew Leifheit for New York Magazine

Cole Escola’s romp Oh, Mary!, which they wrote and star in as a demonic Mary Todd Lincoln, premiered Off Broadway in February. By July, it had become one of Broadway’s biggest hits with celebrities streaming in nightly for backstage meets.

Along the way, the wig-hoarding online funnyperson and downtown cabaret performer became a fashion star. At the Met Gala, they wore archival Thom Browne that made them look like an androgynous child bride in the 1940s (in a good way). They went to the designer’s Fashion Week dinner. “I take my place at the table,” Escola says, “and Martha Stewart looks at me and just says, ‘Are you Mary?’” What seemed like a never-ending flood of famous people — Kerry Washington, Jennifer Aniston, Pedro Pascal, Ben Stiller, Rita Moreno — came to see Oh, Mary! Most of the time, the celebrities don’t faze Escola; the pre–Hays Code melodrama stars who would stun them IRL are long gone. But Moreno means something. Her performance as Googie Gomez in The Ritz was a strong early influence: “Imagine you are a child reading your favorite fairy tale and Cinderella pulls you into the book to compliment your shoes.”

Escola came up in the 2010s, one smart queer idiot in a tidal wave of kin like John Early, Kate Berlant, Patti Harrison, Bowen Yang, Bridget Everett, and Julio Torres. But Escola is the first to storm Broadway. “The best part,” they say, “has been all of the people who I performed with at Joe’s Pub, or who came to see me at the Duplex, seeing the success of Oh, Mary! and the look of pride on their faces.” — Jason P. Frank

Photo: Chris Maluszynski

For decades, the author Paul Auster, who died in April, made his home in Park Slope. He was a fixture around Seventh Avenue and, for a while, big-game prey for literary types who went to the neighborhood hoping to catch a glimpse. “We had many people come to the store from places far and wide asking where they could run into him,” says Stephanie Valdez of Community Bookstore, one of his haunts. “People would leave him notes and letters at the register.” Park Slope businesses, actual and otherwise, show up regularly in his fiction: a local candy-and-cigar shop in his film Smoke, a deli “with the absurd name of La Bagel Delight,” as he puts it in his novel The Brooklyn Follies, in which a character accidentally asks for a “cinnamon-Reagan” bagel and the guy behind the counter shoots back, “How about a pumpernixon instead?” “That really did happen — it was my brother, Dino,” says Frank Bavaro, who co-owns the shop. “He’s a quick thinker.”

“Paul was a gentle, reserved customer,” says one owner of the trattoria Al Di La, where Auster would order the Gavi di Gavi; two blocks down, at Shawn Fine Wines, he bought Joseph Mellot’s Sancerre almost exclusively. With his brooding, silent-film-star looks, he was easy to spot. “He could’ve played a mob boss,” says Bavaro. Auster brought his manuscripts — typewritten — to 7th Ave Copy & Office Supplies, where employee Carlos Fong had figured out how to scan the pages without cutting off the handwritten annotations. “He said, ‘You guys are geniuses,’” says Fong, who doesn’t read novels, only comic books. “He surprised me many years ago, just before Christmas, and gave me a copy of City of Glass but as a graphic novel,” he recalls. “He signed it and wrote, ‘Thank you for everything.’” — Emma Alpern

Photo-Illustration: Illustration by Pete Gamlen, image courtesy of Butterfield Market;

Butterfield Market, a little gourmet grocery on Lexington Avenue, has been an Upper East Side stalwart since 1915. When Joelle Obsatz was growing up above the store, then run by her grandfather and father, “it was like an extension of our fridge,” she says. Like William Poll or Zitomer, Butterfield is an ageless classic (and like most ageless classics in 10021, it has had a little work done from time to time). It was for most of its history a family place stocked with hot food and fresh-baked babka, where the shopkeepers often knew customers by name. “Maybe a lot of people’s grandmas fill the house with a lot of home-cooked stuff,” says Michael Rubel, whose late grandmother, Marge Russell, was a decadeslong Butterfielder. “Her version of making us a special dinner was just waving a hand and saying, ‘Use my house account at Butterfield.’”

Those never–below–42nd Streeters still patronize Butterfield, but so, too, does an enlarging army of TikTokers. The Obsatz family was preparing to open a second location of the market in 2020 when the pandemic interceded. Life moved online, and Butterfield had no choice but to follow suit. Obsatz started reaching out to influencers, who were happy to spread the good word, eventually turning Butterfield into, as some TikTokers put it this year, “the Erewhon of NYC.” Among the collaborations: a sweet-and-savory cruller by @CheatDayEats, an Oreo-stuffed cupcake from @SofiaEatsNYC, and smoothies by @HealthWithHunter. With umpteen private schools in the area, there’s a built-in viral-treats audience that consumes happily alongside the original clientele. “I wouldn’t be the customer for that. I’m not that adventurous,” longtime Butterfielder Casper Caldarola says when asked if she’s sampled, say, the Oreo-stuffed cupcake. As for Marge, she remained until the end, says Rubel, “blissfully unaware of whatever Reels they were putting out.” — Matthew Schneier

Photo: Hugo Yu

You may be tempted, when presented with the $11 dessert the East Village raw bar Penny calls an “ice-cream sandwich,” to think, Well, anyone can do that. It’s ice cream. It’s bread. Case closed. Well, actually, anyone can’t do this. To start, the bread is homemade sesame-studded brioche, soft little slices of essentially a giant Parker House roll. The scoop of ice cream, also made at the shop, is malted milk. The proverbial cherry on top is real fruit, which rotates seasonally. This summer, it was strawberry jam. Plum ushered in the fall. Now, it’s a thin layer of cinnamon-dusted apple butter, a perfect square that, by the way, you probably couldn’t cut yourself either. — Alan Sytsma

Photo: Beth Sacca

At 8:20 a.m. on weekdays, Liam, who is 10 years old and in fifth grade, leaves his Park Slope apartment. His parents, Patrick and Heidi (all names have been changed), say good-bye and assume he’ll get to school on time. “I am not a morning person,” Heidi says. “There was always such a scramble to get out the door. Honestly, I thought, Our kid can get himself to school? This is amazing.” They don’t track Liam with a phone or a watch; a teacher does not text them to announce his arrival.

Not all New York City parents are unleashing their tweens upon the city — unsupervised commutes become more common in middle school, and even then, parents are often tracking — but the free-range, resilience-building childhood that Gen-X and millennial parents say they want for their kids is readily available here. Coverage of subway crime and fleets of zooming e-bikes may have made some parents more skittish, yet the vast majority of children are managing just fine. Check any bus or Starbucks near a middle school around 3:15 p.m. and think of all the parents who aren’t behind the wheel in a carpool line. It’s glorious.

Photo: Beth Sacca

Parental oversight isn’t always the fail-safe we imagine it to be. One mother of an 11-year-old allows him to venture solo to meet friends in Central Park and on playgrounds and worries about very little except his getting hit by a car. She recalls an accident in Corona in 2020 in which a child was struck and killed by a garbage truck. “But then I remember he was walking to school with his mom,” she says. “Us being with our kids doesn’t automatically protect them.”

Adam, a father in Middle Village, says he was very anxious this year about his son, Alex, starting at a high school far from their house. Alex had been walking to middle school ten minutes away by himself since seventh grade. Now, he will need to take two city buses and change in Long Island City. The two of them practiced the commute together. “My son is super-excited,” Adam says with pride. “He’s good with buses.”

My two oldest children — ages 12 and 14 — have been going to and from school on their own for years. They are street-smart, confident, and, best of all, useful. They grocery shop, return their own Amazon purchases, and pick up their younger brother from playdates — and I haven’t darkened the doorway of their orthodontist’s office since 2022. — Elizabeth Passarella

Photo: Courtesy of the subjects

The first thing the Sullivans will tell you is that they really fought. When Ohio lawmakers began introducing a slate of anti-trans bills in early 2021, Emma and Tom knew the measures would directly impact their youngest child, Riley, who is transgender nonbinary. So the family, which had called Ohio home for a decade, showed up to school-board meetings and the statehouse, organized rallies and protests, and submitted testimony opposing the bills by letter and in person. Still, it got worse. Year after year, more anti-trans bills gained traction. Even before they became law, the increasingly hostile debate around them had a chilling effect on Riley’s doctors, who suddenly weren’t comfortable discussing treatments for the teenager, no matter how small. “It was all-encompassing,” Tom says.

As it became clear that some of the measures would pass, the family began talking in earnest about leaving Ohio. Riley (all names have been changed for privacy) had always wanted to live on the East Coast and felt the pull of New York. So last summer, before even securing jobs in the city, Emma and Tom took a chance and signed a lease in Brooklyn. They arrived within a month.

Now, a year later, 500 miles from Ohio, Riley has flourished. The family dove straight into Broadway, ticking off Suffs, Appropriate, Sweeney Todd, and Titanique in their time here. (Next on the list are Oh, Mary! and Suffs … again.) Riley loves live music, and they especially love that here, they can get to concerts all on their own. Treatment moved swiftly; even their standard pediatrician is able to provide the necessary care and medication. There are other things, too, like easily finding gender-neutral bathrooms — a logistical nightmare back home — and overhearing, for the first time, they/them pronouns used in casual conversation.

In January, the GOP-controlled Ohio legislature officially banned gender-affirming care for trans children. Emma still struggles with what she calls survivor’s guilt — many friends back home don’t have the option to leave. But it’s worth it, she says, to see Riley get to be themself. In October, the Sullivans visited their eldest child, who remains in Ohio. As they drove back into New York, Emma says she felt relief wash over her. “It was the first time,” she says, “where I was like, Oh, I’m home.” — Andrea González-Ramírez

Tap or click to zoom in.

Illustration: Peter Arkle

La Chimera, Alice Rohrwacher’s labyrinthine Palme d’Or contender, debuted in early spring — a notoriously tricky time for film releases — and ran for 25 weeks at IFC, becoming the theater’s longest-running movie in nearly a decade and proving, once and for all, we’re still a city of snobs.

Photo: Horst P. Horst/Conde Nast/Getty Images

Among the prospective buyers putting in early bids at Christie’s hot-ticket preview of its series of Mica Ertegun sales was Clifford Streit, who knew the late society fixture and her music-mogul husband, Ahmet. “I bid on a few small things, like a David Salle drawing,” Streit says. “But I was $94 million short for the Magritte.”

Over six live and online sales in November and December in Paris and New York, “Mica: The Collection of Mica Ertegun” has everything from Picassos to a pine-cone basket. Such estate auctions of rich, celebrity-adjacent New Yorkers are festive occasions for those hoping to nab a “pewter-mounted fruitwood squirrel-form bowl” for just $100 or a David Hockney for just $20 million. For others, gawping at the sheer volume and opulence of Ertegun’s stuff is its own illicit thrill, like rifling through the bedroom drawers of a hostess at a dinner party. Ertegun’s own dinner guests were as likely to include stars from her husband’s Atlantic Records roster as her socialite design clients. The refugee from Romania, who worked for the better part of a decade on a chicken farm, loved literature, conversation — and many exquisite objects.

“The galleries have been packed,” says an anonymous Christie’s employee who was caught off guard by the mass appeal of Mica’s tchotchkes. “Visitors have come from all over the world!”

Sprinkled among the hottest of items, you can also find some bargains. “My cousin bid on the torsade necklace,” Streit says. “The estimate is $18,000, which is not a lot of money for how many rubies are in it.” — Ben Widdicombe

Photo: Jeff Chien-Hsing Liao

New Yorkers knew ahead of time that the solar eclipse expected on April 8 wouldn’t put the city into complete darkness. Nor would we be able to see the flash of corona around the sun’s disk that is said to be mind-blowing and life-changing. For that, you’d have had to travel to somewhere on the path of totality, a narrow band from San Antonio to northern Maine that missed the metro region by a couple hundred miles. But around 3:30 p.m., it got dim enough in the city to be spooky-weird for a while, and hordes of office workers and laborers and layabouts alike poured out into the streets and looked up. The steps of the New York Public Library’s Schwarzman Building were full. The NYPD’s 19th Precinct posted a gag video in which one doughnut slowly eclipsed another. Mayor Adams, putting on his eclipse glasses, asks, “Is it supposed to be this dark?” (Yes.) Suddenly, we were all third-graders watching a science demo — and a good one. Perhaps you, like Adams, got proper eye protection in advance, or maybe you were one of the class nerds with a pinhole-camera setup, projecting a little crescent dot on a piece of white cardboard. Or perhaps you didn’t plan ahead at all, in which case you knew not to look but probably still tried to steal a sweeping, only lightly retina-frying glance. Thereafter, as the sun crept back to its normal workday, so did everyone else. — Christopher Bonanos

Illustration: Peter Arkle

“This will not,” said the evening’s host, “be a Seder as usual.” We were on a patch of concrete by Senator Chuck Schumer’s apartment building near Grand Army Plaza that has become, to some Park Slopers’ dismay, a popular and noisy protest hub since October 7.

Hundreds of us sat or stood shoulder-to-shoulder around a giant ceremonial Seder plate. “Seder in the Streets” was a Passover event hosted by a coalition of leftist Jewish organizations whose members’ Jewish bona fides are continually questioned by pro-Israel Jews. This was an attempt to observe but not celebrate. We wanted to participate in the rituals of Passover, which tells the story of the Jews’ exodus from bondage, while also demanding that our government stop spending billions of dollars on Israel’s decades of ruthless occupation of Palestine. Many in the plaza — about 200 in total — would soon be arrested.

It was my choice to make this my first Passover without friends or family. There would be no reclining in dining-room chairs, no search for the afikomen, no kibitzing with my godmother over her homemade apple cake. I was here, saying the Kiddush on the cold ground, because I no longer felt sheltered in the kind of Judaism I grew up in — one that supports our religion’s commitment to social justice but has also embraced an Israeli government that calls for a bloody end to the Palestinian people.

The Seder was a bit like all other Seders (prayers were recited) and also not (there was shouting about Zionism as a false idol). Simone Zimmerman, who broke with her community’s political traditions to co-found an organization called IfNotNow, which lobbies Americans to care about Palestinian liberation, spun the Four Questions into new queries: “What does it mean,” she asked, “to celebrate a holiday about liberation in a moment in which Palestinian lives and freedom are under their most critical assault since the Nakba?” The questions echoed the ones I’d been asking myself since October 7, like, “What does it mean to be against apartheid when some of your own family members helped establish it?” (I’m cousins with both Israel’s first president and its seventh) and more obvious questions like, “What can we do to stop the occupation?” I knew the answers would not come easily. Being among these strangers working through it, I felt at home. — Alex Suskind

Photo: Matt Weinberger

Parking lots are for angsty teenagers stuck in suburbia — and, this year, for every hot, young clout chaser in New York. When a bar called Time Again opened in May on the stub of a dead-end street in Chinatown, the proprietors set out some red and blue plastic stools reminiscent of an elementary-school cafeteria’s. This hangout, wedged in by a public school, a Greyhound bus stop, and a Manhattan Bridge off-ramp, spilled onto the street and became a scene. This was the year Dimes Square finally lost its cool, or at least got overcrowded, so everyone migrated down Canal instead.

In August, GQ declared it, Stefon style, “the hottest club in NYC” and described the crowd as “downright Bourdainian.” (Actually, he would’ve hated the $13 cocktails and small plates.) Soon after, the New York Post exclaimed, “NYC’s hot hangout a parking lot?! They’re chillin’ ‘out’ in the city.” In October, Vampire Weekend performed a surprise show there, just before the scene cooled along with the weather. When the crowd went home for the season, it revealed the joint as just another natural-wine bar in a city glutted with them. Not once, I realized, though I was there much of the summer, had I spent any time inside. “It was such a moment,” says the first person who invited me to party in the parking lot. “It can never be reclaimed.” — Brock Colyar

Photo: Oliver Farshi

When the trio of DJs behind the party collective MUNDO set out to put the Bronx on the city’s rave map, they knew they had their work cut out for them. “When we were growing up, there was never really a scene in the Bronx,” MUNDO’s DJ Guari says. “It was just hookah lounges and bottle-service clubs.” The group started throwing raves in May and have performed around the world, but they struggled to find a venue in their home borough — that is, until they lucked out with a deli in the South Bronx.

That deli became the site of MUNDO’s first-ever bodega rave, and since then, they’ve held one nearly every month, bringing in a growing swath of partygoers as shelves are pushed aside to open up a dance floor and lights strobe from a ceiling draped with flags and tapestries. Gabriella Castillo, a 30-year-old Bronx native who has been following MUNDO since the beginning, says it’s hard to express how much it means to her to see people traveling from Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, and New Jersey to get down in the Bronx. “When I was 15, 16, I used to commute to go to anything that was a community space,” she says.

The final bodega rave of the year was Halloween-costume optional, grooving mandatory. (As always, the location was kept secret until the day of — that’s part of, per MUNDO’s DJ Flako, “the mystique.”) Half an hour after the doors opened, the corner store had transformed into a packed dance club. Slick custom graphics flashed on the row of TV screens set up in place of the usual menu above the counter while DJs worked a deck behind it. Bunny rabbits, Greek goddesses, and one “grandma” sang along to Jersey-club remixes of Sexyy Redd (“SkeeYee”) and Ice Spice (what else but “Deli”?). By 2 a.m., the party was still alive and well — even the shop’s owner remained among the crowd. “I never thought that anybody would give a fuck about the Bronx,” says Castillo. “But they threw a rave in a bodega and made that shit pop on the news. You have to understand the magnitude of that!” — Katie Way

Illustration: Peter Arkle

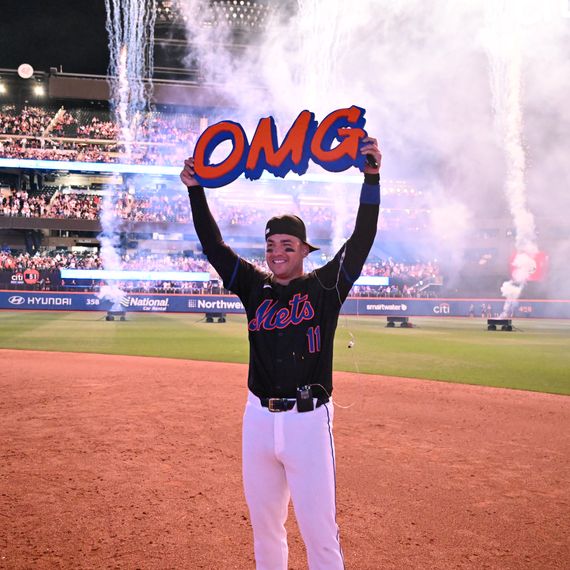

Photo: New York Mets/MLB Photos via Getty Images

Jose Iglesias was recording music in Miami last offseason when he got the call: The Mets wanted to sign him. The infielder — who creates Latin pop under the name Candelita — had played more than a thousand games with six teams but didn’t crack a major-league roster at all in 2023. This year, he became an unexpected source of Mets mojo, not just because of his on-field play — he ended his season with a 22-game hitting streak — but thanks to a track laid down in that Miami recording session: “OMG,” a rabidly catchy song about fighting for your dreams, which became the anthem of one of the most memorable seasons in Mets history and a Billboard No. 1 hit.

At the urging of veteran J. D. Martinez, Iglesias first played the track for his new teammates in May; they encouraged him to begin using it as his walk-up music before at-bats. As the Mets turned their season around after an inauspicious spring, the song began playing on repeat through the clubhouse speakers following victories. Players started sporting OMG T-shirts. Fans wore OMG chains. A Middle Village butcher shop created an OMG sandwich on purple “Grimace bread.” (The blobby mascot became a Mets celeb this summer after throwing a ceremonial first pitch that coincided with a seven-game winning streak.) Following a June win over the Astros, Iglesias performed the song live for 30,000 fans. An acrylic OMG sign — created by artist Jerome McCroy — became a trophy presented to players after home runs. When the O fell off the original, McCroy drove six hours to Pittsburgh to deliver a replacement. Why? “I was a season-ticket holder for years,” he says. “Nothing has compared to what this season has made me feel.” — Joe DeLessio

Illustration: Peter Arkle

Geo and Patrick at a Stud Country party at Brooklyn Bowl in January.

Photo: Weston Kloefkorn

Geo Jedlicka and Patrick Ross met on Labor Day weekend in 1990 at the Ice Palace in Cherry Grove. There was an early-evening hoedown hosted by the Times Squares, a gay and lesbian square-dancing troupe. Patrick was attending as an angel — square-dancing lingo for a volunteer who teaches the newbies all the right steps — and Geo was new. Patrick, with his unplaceable accent, “like a slight twang,” and “electric-blue eyes and dark hair,” offered to give Geo a lesson. Geo especially liked his facial hair: “I’ve always been attracted to a mustache.” Their first dance together was the Texas two-step.

Both were in serious relationships with other men. But two years later, single again, Geo remembered Patrick’s moves back on Fire Island, and he called him up to invite him to a dance in New Jersey. Patrick said “yes.” “Shortly after, he said he was going to leave his partner for me,” says Geo, now 57.

Patrick was from Cheyenne, Wyoming, and had moved to New York after a stint in the Peace Corps teaching English in Saudi Arabia, Japan, and South Korea. Geo was a Queens native living in Maspeth.

Patrick was an introvert; when they met their friends at a piano bar, Geo drank beer and sang show tunes while Patrick silently sipped tea in the corner. When they traveled to square-dancing conventions around the country, Patrick drove and Geo read aloud from Harry Potter, Pride and Prejudice, and Stephen King. “I packed his clothes for trips,” Geo says. “He didn’t have the gay gene that helps in that sense.” (Geo also cut their hair — very similar but slightly different graying flattops — at home.) “I was more of the planner. If somebody asked him about something, he’d say, ‘Check with Geo.’ I got him to do many things he might not have.”

Like a lot of couples, they had songs they felt belonged to them: “Outbound Plane,” by Suzy Bogguss; “Gandhi/Buddha,” by the lesbian folk singer Cheryl Wheeler; and “Forever and for Always,” by Shania Twain. “If we heard the first few notes of those songs at the Ranch” — that would be midtown’s country-western dance venue Big Apple Ranch — “and someone came up to me, asking, ‘Do you want to dance?,’ I’d say, ‘Sorry, this is my dance with Patrick.’ ”

They became serious hobbyists and jokingly identified as “bi-dansual,” meaning in the rather traditionally gendered world of cowboy hats and crinoline skirts, they would take turns dancing the boy part and the girl part. “When you’re there, your mind can’t go to anything else. You’re in the moment, working as a team,” Geo says. “Having this common activity that we both enjoyed is an awesome glue for a relationship.”

In 2002, the couple moved to a townhouse in Jersey City, which they renovated themselves, reading up on how to install crown molding. In 2007, the year it became legal in New Jersey, they joined in a civil union at the courthouse down the street. Through the decades, they parented eight cats together — Henry, Echo, Trex, Otter, Anubis, Jekyll, Hyde, and Phoebe — plus a Siberian husky, Noon Khe. “Patrick was coming out of his shell more,” says Geo. “I think the dog changed him. It gave him a more carefree, happier demeanor.”

With age, Geo says, they grew to share more in common. A love for Broadway, for one; Patrick was partial to Evita. Every year, they took a big trip, most recently to Machu Picchu. They were never, Geo says, big partyers, but when visiting other cities, they would usually seek out the local leather bar. They were nudists and enjoyed trips to Gunnison Beach.

When Stud Country — a Gen-Z-forward queer line-dancing party — started up in New York after the pandemic, Geo and Patrick decided to give it a whirl. They enjoyed watching the kids adopt their longtime hobby, if not what they considered the rather elementary moves. “We loved the energy. Why aren’t we getting crowds like this? Where are these people coming from? Patrick was probably the oldest one there,” Geo says. They became regulars at Stud Country’s parties, though the music was more likely to be Troye Sivan or Kesha than Twain.

This year, Patrick, 70, was going to retire for good from his job as a banker. They also figured they might finally get married. They talked, half-jokingly, about leaving the country if Donald Trump won again. Their two requirements for a new home base: somewhere with gay people and square-dancing. In March, after a turn on the dance floor at one of Stud Country’s parties, Patrick collapsed. He died three days later.

Patrick’s memorial was held in August at P.S. 3 on Hudson Street, the public school by their old apartment where the Times Squares often held dances back in the day. Geo gave a eulogy: “A friend of Dorothy but didn’t need any of Oz’s gifts. He already possessed a beautiful brain, a pure heart, and courage.” Also, he tells me later, “he still, even as an older gentleman, had his looks.”

There was a memorial square dance at the service. Geo danced alone with “a phantom Patrick,” he says. After 32 years together, there’s maybe a little comfort knowing his lover died doing what they both loved. “We met on the dance floor,” Geo says. “We parted on the dance floor.” — Brock Colyar

Source link