Seven Books to Read in the Sunshine

As spring takes hold, the days arrive with a freshness that makes people want to linger outside; the balmy days almost feel wasted indoors. While you’re taking in the warm air, you might as well also be reading. Enjoying a book at a park, a beach, or an open-air café encourages a particular leisurely frame of mind. It allows a reader to let their thoughts wander, reflecting on matters that for once aren’t workaday or practical.

Reading outside also takes the particular pleasures of literature and heightens them. The proximity of trees or of other human beings, or the sight of a page illuminated by the sun, can make a character’s search for connection, or a writer’s emotion recollected in tranquility, feel more visceral and alive. And whether you’re reading on a front stoop or on a train station’s bench, being alone yet somehow with others creates a kind of openness to the world.

The books below will suit a variety of outdoor readers, including those who get distracted easily by the hustle and bustle around them and those who want meaty works to dive into. Each one, however, asks us to think about our place in the world or invites us to appreciate beauty, or sometimes both at once—the same sort of perspective we happen to gain outdoors.

The Art of the Wasted Day, by Patricia Hampl

To fully appreciate this book’s defense of luxuriant time-wasting, might I suggest reading it while sprawled on a beach towel or suspended in a hammock? “Lolling,” Hampl argues, is “tending to life’s real business.” She stumps against a particularly American obsession with striving and accomplishment in favor of leisure—a word that comes, by the end of the book, to encompass reading, writing, talking, eating, walking, gardening, boating, contemplative withdrawal, and … lying in hammocks. Fittingly, her case is constructed as an associative meander through literature, her own memories, and the musings they kick up. An anecdote about daydreaming while practicing the piano at her Catholic girls’ school shifts seamlessly into a riff on the true meaning of keeping a diary; she takes trips to Wales, Czechia, and France to see the homes of historical figures who sought lives of repose, particularly Montaigne, whose “sluggish, lax, drowsy” spirit haunts the book. There’s nothing practical about the scraps of experience, passing thoughts, or remembered sensations that make up a life. And yet, Hampl writes, these idle moments we carry with us are “the only thing of value we possess.”

By Patricia Hampl

An Immense World, by Ed Yong

The natural world is thrumming with signals—most of which we humans miss completely, as Yong’s fascinating book on animal senses makes clear. Birds can discriminate among hundreds of millions of colors; bees pick out different flowers by sensing their electrical field; elephants communicate over long distances with infrasound rumbles; cows can perceive the entire horizon around them without moving their head. Yong, a former Atlantic staff writer, brings the complexity of animal perception and communication to life with an unmistakable giddiness, because evolution is wild. Catfish, which are covered with external taste buds, are in effect “swimming tongues”: “If you lick one of them, you’ll both simultaneously taste each other,” he explains. But beyond its trove of genuinely fun facts, the book has a bigger project. “When we pay attention to other animals, our own world expands and deepens,” Yong writes. Even parks and backyards become rich, fantastic worlds when we imagine, with the help of scientific research, what it’s like to inhabit the body of a different creature. Take this book outside—its insights will make you see the animals whose world we share with a new precision and wonder.

By Ed Yong

If Not, Winter: Fragments of Sappho, by Sappho, translated by Anne Carson

Hardly any of Sappho’s work survives, and the fragments scholars have salvaged from tattered papyrus and other ancient texts can be collected in thin volumes easily tossed into tote bags. Still, Carson’s translation immediately makes clear why those scholars went to so much effort. Sappho famously describes the devastation of seeing one’s beloved, when “tongue breaks and thin / fire is racing under skin”; the god Eros, in another poem, is a “sweetbitter unmanageable creature who steals in.” Other poems provide crisp images from the sixth century B.C.E.—one fragment reads, in its entirety: “the feet / by spangled straps covered / beautiful Lydian work.” Taken together, the fragments are sensual and floral, reminiscent of springtime; they evoke soft pillows and sleepless nights, violets in women’s laps, wedding celebrations—and desire, always desire. Because the poems are so brief, they’re perfect for outdoor reading and its many distractions. Even the white space on the pages is thought-provoking. Carson includes brackets throughout to indicate destroyed papyrus or illegible letters in the original source, and the gaps they create allow space for rumination or moments of inattention while one lies on a blanket on a warm day.

By Sappho

Samarkand, by Amin Maalouf

No matter where you’re sitting—a hard bench, a crowded park lawn—great historical fiction can whisk you away to a lush, utterly different place and time. Maalouf’s novel tells two stories linked by a priceless book of poetry. The first follows the 11th-century astronomer and mathematician Omar Khayyam as he travels to the cities of Samarkand and Isfahan and records stray verses that will one day become his famous Rubaiyat. In the second, set in the late 19th century, an American named Benjamin Omar Lesage narrates his pursuit of this “Samarkand manuscript,” a quest that takes him to Constantinople, Tehran, and Tabriz. Both men remain devoted to art and love despite the violent political turmoil around them—Omar must deal with power struggles in the imperial Seljuk court and the rise of a terrifying Order of the Assassins; Benjamin lives through Iran’s Constitutional Revolution. Interwoven with this fascinating history are glimpses of bustling market squares and palace gardens, plus legends of conquerors and half-mad kings, all of which make Samarkand vivid enough to compete with the distractions of the world around you.

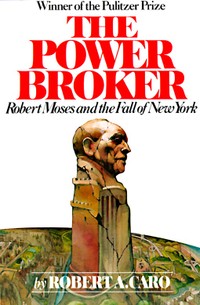

The Power Broker, by Robert Caro

Maybe you’re feeling particularly motivated: You’ve found a prime spot on an underappreciated patio or a secluded beach, and you’re ready to spend the summer there, immersed in a single monumental work sturdy enough for multiple outings. Why not tackle this classic biography of Robert Moses, the 20th-century urban planner and New York City political insider, whose more than 1,000 pages will last you the entire season? The Power Broker charts Moses’s rise from an idealistic reformer of municipal government to a vindictive public official who was personally responsible for building hundreds of green spaces, roads, bridges, and housing projects that utterly changed New York’s landscape—often to the detriment of its citizens. Caro organizes his book around a careful account of Moses’s power: how he got it, kept it, and accumulated such stores of it that he became unanswerable even to the mayors and governors he ostensibly served. The book manages to make the dry business of an endless array of park councils and bridge authorities riveting, and it offers sobering lessons on how a single unelected official—particularly one as racist, classist, and arrogant as Moses—can wreak havoc on those without power.

By Robert A. Caro

Adèle, by Leila Slimani

Adèle, a story about a woman’s insatiable appetites, is easy to devour. It’s twisty, a little dark, and very absorbing, told in cool, inexorable prose stripped of ornament but full of psychological depth. It is, in other words, the perfect literary beach read—a book riveting enough to keep you turning pages when your brain is in vacation mode, and written with a care that adds to the story’s pleasure. The novel’s title character seems bent on destroying the trappings of her perfect life: Adèle has sex with her boss at the newspaper where she performs her work half-heartedly, starts an affair with a friend of her solid but sexless gastroenterologist husband, and invites men to her large apartment in Paris’s 18th arrondissement. But her dalliances are oddly unsatisfying. She recoils, during one episode, from “the banality of a zipper, the prosaic vulgarity of a pair of socks.” The book’s dramatic tension comes in part from the increasing untenability of her hidden life. Below the level of plot lurks the question of what Adèle is really after, and one can’t help but race through the book, mining each page for tantalizing clues. Is it “idleness or decadence” she wants? Or is her compulsion “the very thing that she thinks defines her, her true self”?

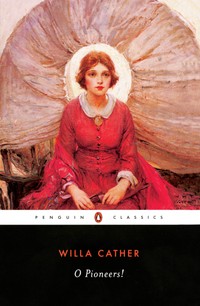

O Pioneers!, by Willa Cather

This novel, set in the closing decades of the 19th century and suffused with the wide-open lushness of the Nebraska prairie, practically demands to be read in the open air. When her father dies, Alexandra Bergson is entrusted with the family farm and soon becomes prosperous, thanks to some canny risk-taking and her near-mystical identification with the land. Her happiest days, Cather writes, come when she’s “close to the flat, fallow world about her” and feels “in her own body the joyous germination in the soil.” That’s a joy that pervades the book, despite a subplot involving an illicit romance that ends in tragedy. We’re treated to intoxicating descriptions of cherry trees, their branches “glittering” after a night of rain, and the air “so clear that the eye could follow a hawk up and up, into the blazing blue depths of the sky.” The book’s short length is perfect for whiling away an afternoon, perhaps under a tree on a sun-drenched day—the better to appreciate a pivotal scene set in an orchard “riddled and shot with gold.”

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

Source link