The Altneu Synagogue Buys the Thomas Lamont Mansion

The Thomas Lamont mansion went up for sale last year for the first time since it was built in 1922.

Photo: Sotheby’s

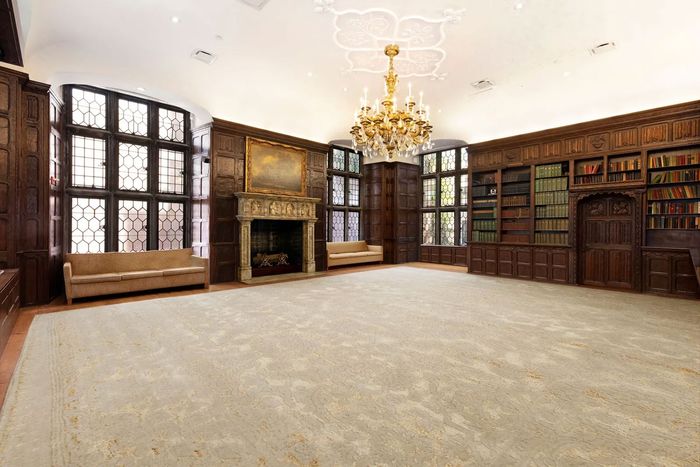

There aren’t a lot of townhouses in New York City like 107 East 70th Street. The stone-and-brick Tudor Revival looks more like an Ivy League library than a family home, partly because of its scale — six stories high, 55 feet wide — and partly because of its leaded-glass windows, wood-paneled library, and an original Gothic fireplace carved with tiny toiling nuns. This all goes to explain why the building was listed at $45 million last year — enough to buy four separate townhouses up and down the block.

That listing, in March 2023, was the first time the 23,000-square-foot home has been put up for sale since it broke ground over 100 years ago, and last week, a buyer finally closed. The Altneu, an orthodox synagogue, says it’s paying $34.5 million for the building; the broker for the seller declined to comment.

The synagogue was founded just three years ago by a young rabbi who split from one of the city’s most established and moneyed Modern Orthodox synagogues, the 130-year-old Park East Synagogue a few blocks away. At first, the crowd that followed him met in his apartment; eventually, they began renting out ballrooms up and down the East Side, flitting between the Asia Society, the Pierre Hotel, and the Explorers Club, with stints at the Alliance Française and the Harold Pratt House. At one point, the various locations “made it appealing,” said Gideon Etra, a member from the beginning, who enjoyed the “process of discovery” in tracking down new addresses. But the logistics were a nightmare that required an event coordinator and endless reminders about where to show up. “This is the one shul where you really have to read your emails,” joked Rabbi Benjamin Goldschmidt, who said he did not enjoy “telling a Jewish mother you don’t know where her son’s bar mitzvah is going to be in three weeks.”

Rabbi Benjamin Goldschmidt and Rebbetzin Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt outside the home.

Photo: Daniel Landesman

Now, they do. Goldschmidt says the building came to them by a “divine hand” but also gave credit for finding the space and fundraising to a board that includes bankers, CEOs, and a Blackstone executive. The goal is to get inside the building by Passover with no drastic renovations. Etna, a real-estate investor and incoming board member, says they plan to hold services in a great room on the ground floor, to turn an oak-paneled library into a batei midrash to study Torah, and put more classrooms upstairs. Then there’s the walled yard. “There will definitely be a sukkah in the garden,” said Goldschmidt.

Leaded windows. The home has a side yard, allowing light in on three sides.

Photo: Sotheby’s

The mansion was built in 1922, incidentally for the Presbyterian son of a Methodist pastor, Thomas Lamont. The financier (whose memoir is titled My Boyhood in a Parsonage) is now best known for his work as a statesman — working out deals to uphold the economies of Germany, France, and Italy after World War I. He and his wife Florence were renting when they bought three separate townhomes, and their interest in Tudor Revival may have come out of their Presbyterian religion — also rooted in 16th-century Britain — or their interest in English religious spaces. (They donated half a million dollars to restore Canterbury Cathedral in 1947.) “It’s almost the last thing you’d pick if you were choosing a historic style out of the aether to choose for a synagogue,” said Louis Loftus, a Ph.D. candidate at Princeton who has studied the Jewish uses of Tudor Revival buildings. (He was especially interested in 770 Eastern Parkway, the brick Tudor Revival mansion built around a central oriel window that is now the home of the Chabad Lubavitch, but he also cited an example that may be more familiar to Manhattanites: Zabar’s.)

A mantel in the oak-paneled library is an imported Gothic antique, according to a 1922 article in Architectural Record. The stone is carved with figures of nuns.

Photo: Sotheby’s

When Florence Lamont died in 1954, she donated the house to the Visiting Nurse Service, now known as VNS Health, the oldest nursing organization in the country devoted to public health. The group used it for meetings and office space and renovated in 2009, but its “real-estate needs changed” during the pandemic, according to a spokesperson. The mansion’s past as a bright, functional office space for nurses and as a grand home filled with fine details seemed right for a congregation that Rabbi Goldschmidt said is striving to be “elegant, but not formal.” Aliza Licht, a member and brand strategy consultant, described it as “chic.” “It’s this idea of bringing back classic, sophisticated New York,” she said, which fit with the group’s years of wandering through East Side hotel ballrooms. “This particular space is so on-brand for them.”