The Line at St. Brigid Where NYC Migrants Must Wait

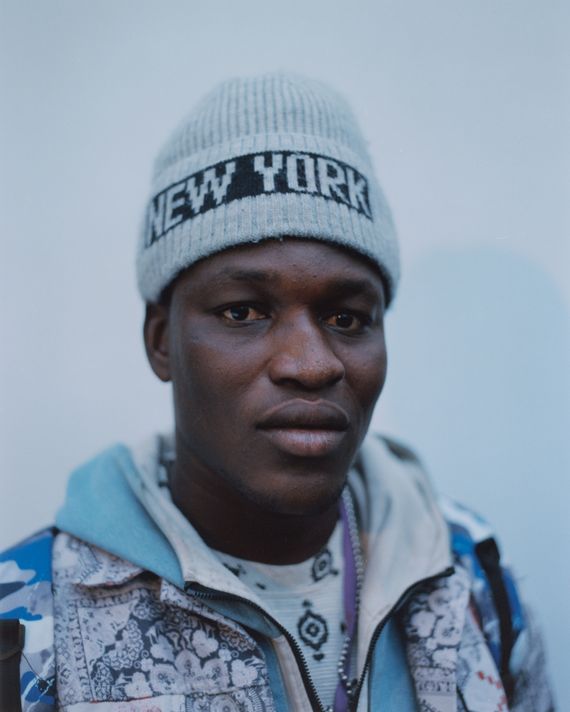

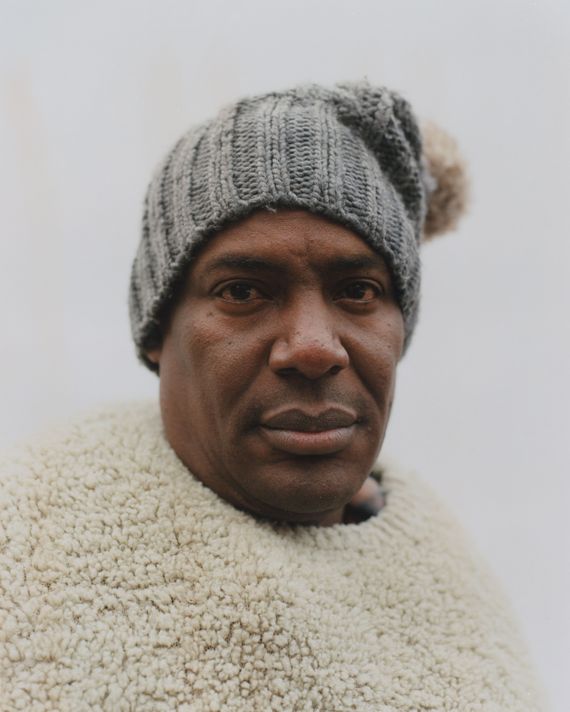

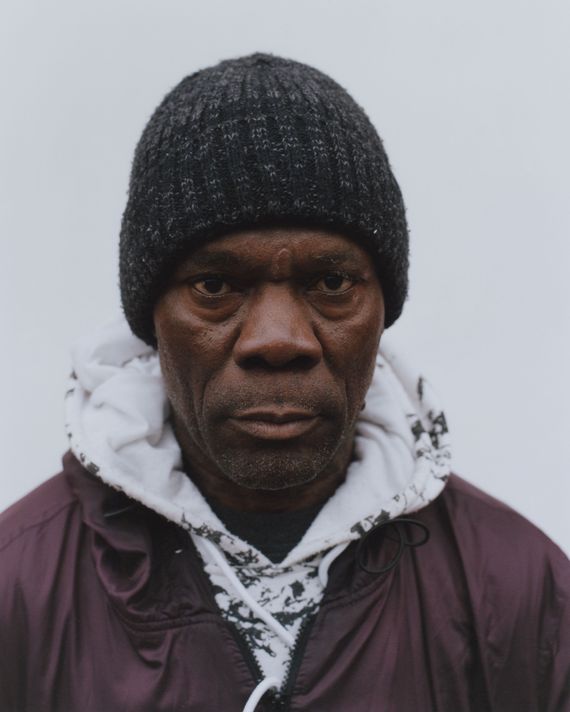

Top row, from left: Ibrahima D., 24; Kaibe, 24; and Mamadou H.D., 39. Second row, from left: Aliou, 23; José, 56; and Moussa, 33. Third row, from left: Yonathan, 50; Enrique, 30; and Mario, 25.

Photo: Philip-Daniel Ducasse

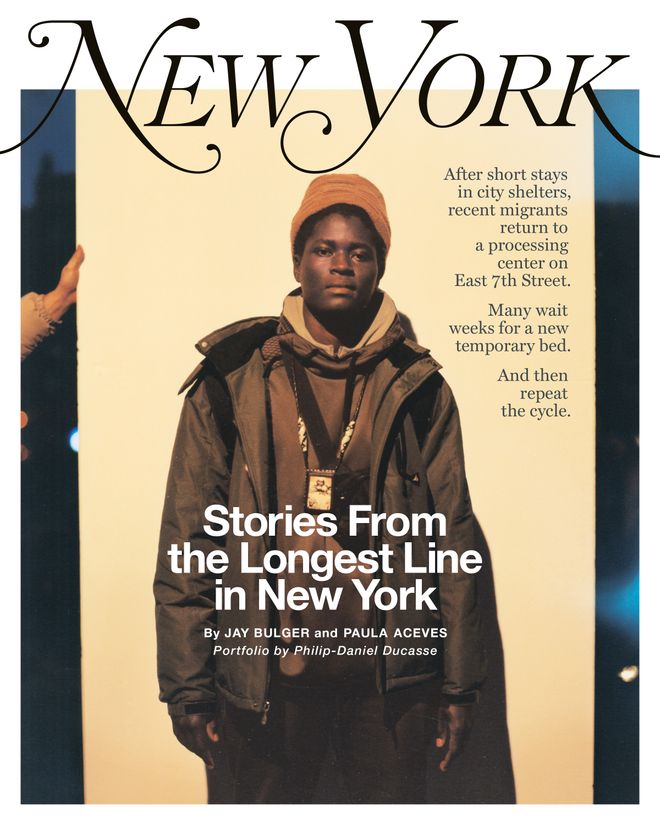

In October, a line started to form outside St. Brigid, a former Catholic school on the corner of East 7th Street at Tompkins Square Park. No one in the neighborhood really knew what it was. Soon, hundreds of people — almost exclusively men, almost exclusively underdressed for the freezing weather — began arriving around five every morning and staying until evening. The line became longer as the year ended, and by mid-January, as temperatures dropped into the 20s, it was more of a throng.

Stories From the Longest Line in New York

See the Issue

St. Brigid had been quietly transformed into what City Hall describes as a “reticketing center,” the first in the city: a place where migrants can be processed into a new shelter after their stay in another one runs out. Shelter stays never used to be time-limited. The city’s “right to shelter” decree, which has been in place since the 1980s, technically guarantees every person in need, including migrants, a safe place to stay. But as the migrant surge has continued — 178,600 have arrived since the spring of 2022 with a notable recent influx of Africans who have flown to Central America and crossed the southern border — the Adams administration has been working to subtly push single migrants out of the system entirely. Over the summer, the city instituted a 60-day limit on shelter stays for single adult migrants. In September, that limit narrowed to 30 days. Adams seemed to hope the inconvenience of reprocessing would discourage applicants, and, in fact, the city offers anyone at St. Brigid a free plane ticket to anywhere in the world. The length of the line — with a wait time that can stretch to two weeks — reflects a colossal civic miscalculation.

Over the past month, we spoke to dozens of people in line at St. Brigid. Their journeys here were almost always harrowing; they recounted near-death experiences, kidnappings, and lost loved ones. Life in New York has, so far, been exhausting and dispiriting. “We are going to wait 15 days before we find a new shelter,” says Mohamed, a student from Mauritania who left because he feared for his life. “We are living on the streets, and we are suffering a lot. But we can’t ask for more.”

From left: Mamadou A.D., 21, Guinea, arrived December 2023Rosa, 55, Colombia, arrived December 2023

From left: Mamadou A.D., 21, Guinea, arrived December 2023Rosa, 55, Colombia, arrived December 2023

From left: Mapate, 32, Mauritania, arrived June 2023Fernando, 41, Ecuador, arrived November 2023

From left: Mapate, 32, Mauritania, arrived June 2023Fernando, 41, Ecuador, arrived November 2023

The city is working to open more shelters (in January, the Adams administration finalized a $77 million contract with 15 hotels across Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx), but those will be reserved for migrants with families. Competition for beds for single adult migrants is fierce. At St. Brigid, migrants are given a number and have to return every day until it’s called. If they’re not there, they won’t receive their spot. While they’re waiting for a new assignment, their only options for sleeping are the five overnight “waiting rooms” set up in various churches across the city. These offer no beds, food, or showers and are available exclusively for overnight stays. And of the 3,500 waiting for shelter recently, only 850 ended up in a waiting room. The rest mostly sleep on the subway or the street.

Bryan, 41, Ecuador, arrived December 2023: It’s already going to be 15 days here in the line. I am waiting for a shelter that can take me, but I haven’t heard anything. We live our lives in these lines. My family, just like any family, is suffering knowing that I’m out here in the street.

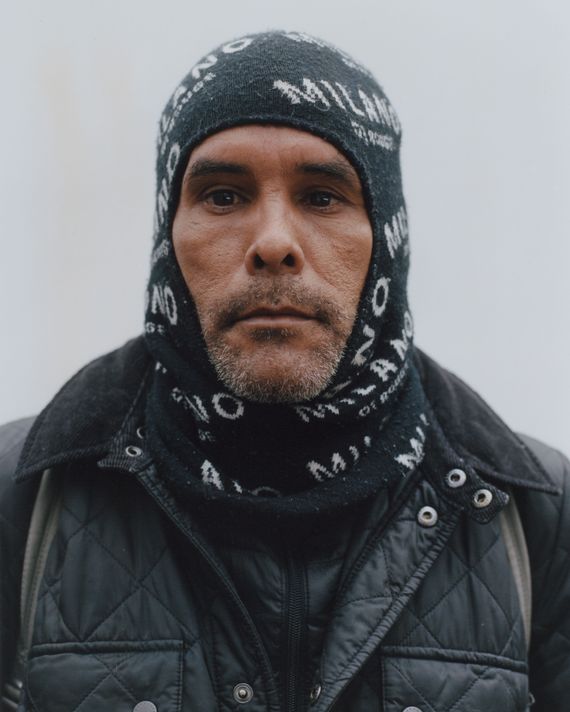

Mamadou H.D., 39, Guinea, arrived September 2023: Last time, I came here at 4 a.m. Because there are so many people waiting, you have to come very early. The first time, I found a new shelter in a single day. But at the moment, it’s difficult — you have to wait here for a week or even 15 days.

Enrique, 30, Ecuador, arrived April 2023: My number is in the 17,000s.

Wuilmer, 45, Venezuela, arrived October 2023: I spend all day on the line, and at night I sleep on the streets or in subway stations. I’ve seen a lot. Sometimes, here, they humiliate you because you are Venezuelan. Not long ago, I was at the train station and someone came and threatened me. He spat on me, on my jacket. I had to stay calm. I didn’t act on my anger because I don’t want to do that here. I’m not in my country. I miss my family.

Rosa, 55, Colombia, arrived December 2023: We wake up at 5 a.m. I wait all day long and then go back to a waiting area in the Bronx at 6 p.m. to sleep on the floor. It’s ugly. I was 54 when I crossed the jungle. The journey was long. My feet hurt. I had to cross a river to turn myself in, and I had water up to my neck. I thought I might drown. I thought I could die. The current. I grabbed on to a man crossing with me. Now I’m 55. My body hurts.

Diomedes, 34, Ecuador, arrived September 2023: If you sleep at the church, you have to sleep on the floor, and they don’t give you food. Just water and a strange kind of cookie. And maybe an orange. Everyone is in competition with everyone else — it’s like you’re at war.

Bryan: Sometimes we go eight days without a bath. And for me, it’s like, I have never lived like this. Never in my life have I slept on the street. I lived well in my country. I had a small business. But I was extorted and told I had to pay the cartel $1,000 monthly. I told them, “Where would that money come from?” And they threatened me, my wife, and my whole family. My wife went to Chile to see if she could find a job there, and I came here. One of us had to come here first to see what it was like, to try it. In a way, it is good because now both of us don’t have to suffer what I am suffering here. It’s not what I expected. I thought I’d be able to put in the work.

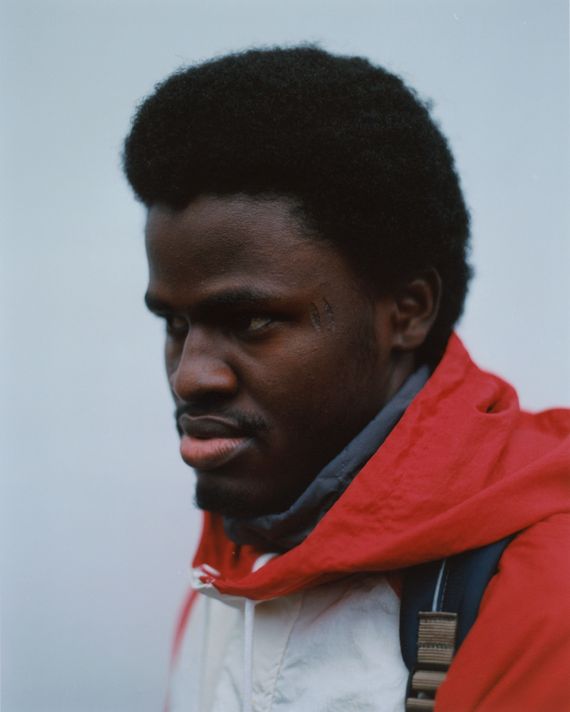

Ibrahima, 24, Mauritania, arrived July 2023: I had to take the subway to find shelter, but it’s not easy to get around without a MetroCard. You can’t take any risks. I’ve slipped through a lot of emergency-exit gates. I was very scared. I’d like to keep my immigration file clean. But you can freeze to death outside.

Wuilmer, 45, Venezuela, arrived October 2023.

Once a person has secured their next 30-day stay in a shelter — on Randalls Island, say, or in the Candler Building in midtown — things aren’t much better. There are often as few as two bathrooms per 90 people; the showers can be in trailers outside. Food is scarce, and often it’s almost inedible, according to several people we spoke to. Drug use is rampant, as are fights — in January, 18 people were arrested on Randalls Island following

the fatal stabbing of a 24-year-old man. (Three people were later charged.) Migrants often spend their days out in the streets looking for jobs or congregating in areas — like outside St. Brigid — where volunteers reliably bring food and clothes.

Ibrahima D., 24, Guinea, arrived December 2023: In my shelter, there are 700 or 800 people. They give us a little sandwich in the morning, a little sandwich at lunchtime, a little sandwich around 4 p.m. A snack so we don’t starve to death. At night, they give us a little serving of rice. It’s hard to sleep with all these problems in your head. At some point around 11 p.m., they turn off the lights.

Diomedes: The food is … ugh. One of the chefs told me that she had previously cooked in a hostel in Brooklyn. She said the food she cooked there was appetizing. But this food they give us is dog food. She said that herself. I had $120 in my pocket, and since that food isn’t good or nourishing, I had to eat out. Because of that, I’m now penniless and have to eat the food here. But, really, it is a meal not even prisoners would eat.

Bryan: The shelter in Brooklyn where I’m staying now is running out of food. Before, they would give us food three times a day. Now it’s only from 6 to 10 a.m. We get a carton of milk, a piece of bread, and two oranges.

Luis: Everyone is fending for themselves. They turn against one another. I had a problem with one of them. He was going to steal a phone charger from me. I didn’t like that, so I tried to get it back, and he pushed me. There were blows.

Alma, 23, Guinea, arrival date unknown: We are afraid to go out. We don’t have enough to buy SIM cards, which means we don’t have any GPS. Still, I’d rather be here than home. I came here with my sister. We had to leave Guinea when my father brought home his second wife. Since I was the oldest — 17 years — she arranged for me to be married to an old man. He was 50; I’d have been his third wife. We fled.

From left: Steven, 25, Ecuador, arrived October 2023Amadou, 38, Guinea, arrived December 2023

From left: Steven, 25, Ecuador, arrived October 2023Amadou, 38, Guinea, arrived December 2023

From left: Diomedes, 34, Ecuador, arrived September 2023Bryan, 41, Ecuador, arrived December 2023

From left: Diomedes, 34, Ecuador, arrived September 2023Bryan, 41, Ecuador, arrived December 2023

Undocumented migrants have historically relied on family to support them through the process of applying for asylum and obtaining work authorization. But for some, the surge in migrants seems to have even overwhelmed these once-dependable ties.

Steven, 25, Ecuador, arrived October 2023: When I decided to leave Ecuador, I called my uncle. He’s an American citizen. He says, “Yes, nephew, the second you put a foot in the United States, call me.” You have to travel on foot in Mexico. I saw people who looked about 80 years old who were walking with a limp, all swollen and scarred. When I got to San Antonio, I called my uncle. He hung up. I wrote to him. He didn’t respond. But he called my sister and he told her, “I think the coyotes took Steven.” The coyotes? I’d already sent her a photo of myself here. And he’d told me the week before to call him, no matter what. When my brother calls him, he says, “No, I don’t have any way to help him. I don’t know who told him I was going to help.” And then I wrote to a cousin, an uncle, so many people — so many “nos.” It was December, and they said that the houses were full, relatives were coming, and they couldn’t help. I said, “I’m just looking for a space where I can sleep; I can leave during the day to look for a job” — but no, no, no, no. Finally, they stopped answering; they didn’t want to know me anymore.

Fernando, 41, Ecuador, arrived November 2023: I went to New Jersey. I called my niece, and they gave me a space in the living room. And I thought that because they were my family, they would support me. But it was not like that. They sent me away, you could say. They told me to get out of there.

Moussa, 33, Senegal, arrived August 2023: I have family all over the United States. They’ve been here for a very long time. None of them wanted to have me in their home. I wouldn’t be here suffering today otherwise. I don’t want to be in a shelter for 30 days and then have to live on the street for ten days without eating, without taking a shower.

Ibrahima: I have distant relatives here in the States. Once you’re here, you call them and they tell you, “No, I can’t help you.” So you have to be strong. You have to stay at the shelter.I talk to my parents from time to time, but not about New York. It’s a mess in their country. I say, “I’m healthy and I’m eating.” That’s all.

From left: Alassane, 28, Senegal, arrived December 2023Alma, 23, Guinea, arrival date unknown

From left: Alassane, 28, Senegal, arrived December 2023Alma, 23, Guinea, arrival date unknown

From left: Mompoint, 27, Haiti, arrival date unknownIsaac, 25, Colombia, arrival date unknown

From left: Mompoint, 27, Haiti, arrival date unknownIsaac, 25, Colombia, arrival date unknown

Those from countries that are especially dangerous to return to — including Venezuela, El Salvador, and Haiti — are eligible for “temporary protected status,” which, if granted, allows them to work legally. This can take anywhere from one to five months, depending on, as one lawyer puts it, “complete dumb luck.” Migrants from a country that doesn’t fall under TPS, like Guatemala or Guinea, may apply for asylum, but they are likely to be rejected. Applying for TPS or asylum also requires documents that many no longer possess. Some migrants lost their passports along their journey; others had them taken by Border Patrol when they were detained. Still, people have to find a way to support themselves, which often leads to exploitative situations.

Diomedes: I have no idea how to obtain citizenship; I have no idea how to obtain a work permit. At the shelters, they help you get a New York ID, and once you get that, they give you forms about residency and asylum. There’s a lottery for that, I think; I don’t know. I haven’t been told anything. I’m waiting to get the address of where to go for Social Security. The first time I registered for asylum, I went back after I hadn’t heard anything to get more information, and it turns out that I wasn’t registered anymore. They told me that I had to get a lawyer to be able to apply for asylum and that they would help me get those papers. But since I don’t have any money, I haven’t been able to get a lawyer. They say that there are also government lawyers, but I have not gotten any instructions on how to get one.

Wuilmer: To work in construction here, you have to have something called an OSHA. But that’s a process. You have to take a class that costs about $180. And if you’re not working, how can you afford to take the class?

Diomedes: I found someone who was already living here, and they offered me a place to stay in exchange for work. I had to clean three buildings, sort the garbage: plastic, glass, cans, cardboard, and what’s in the trash. It took me until 2:30 a.m. every night. And they gave me a room. Well, you can’t really call it a room, but it was a place to sleep. A floor. But they didn’t pay me or give me food or anything.

Fernando: A few months ago, I went to Pennsylvania. I met a man there who offered me a job. A contractor. He told me not to ask how much I’d get paid. He said to work, “and when it’s your turn to get paid, that’s when you’ll get paid.” I had nowhere to live, so he told me I could live where I was working for a week, but then I’d have to find my own place. This man was from Machala. My compatriot. He paid me $10 an hour to demolish a house. That job is very hard and super-complex. I slept in the house, too, in a room full of dust. Eventually, he said I couldn’t sleep there anymore. And I couldn’t find anywhere to live. So I came back here. And now I’m on line again.

Bryan: We have looked for work very hard, but many doors have been closed to us because of the winter, or because we are foreigners who do not have legalized papers, or because we do not speak English. There’s also the fact that if you hire me and I do a bad job, you’ll say, “Oh, these Ecuadorans.” You’re not talking about an individual Ecuadoran anymore; you’re talking about Ecuadorans. Everything is colored by it.

Jonathan: I have tried to look for work in restaurants, washing dishes or doing maintenance. But they’ve told me “no,” that I need documents. Sometimes I collect recycling. Other times I try to resell clothes I’ve been given. One restaurant gave me a job for a day, for four hours. I made $50. I went to Western Union to send $40 of that to my family. The clerk told me that I couldn’t be there if I didn’t speak English. She made me leave.

Mepate: I go to Home Depot and ask, “Do you need help?” I help people who buy equipment at the store unload the material at construction sites. They pay you $20 an hour sometimes. It’s not bad. With the money, I buy food from Arab street vendors because the food people give us at shelters is not enough.

Moussa: I do some buying and selling. Kind people give me clothes, and when something is donated to me but doesn’t fit me, I sell it to someone in the shelter. Sometimes I find shoes that are still in good condition, winter jackets. I don’t want to be too mean because it was given to me for free. So if I see that a customer is friendly and kind, I give it to him for free. But if I used my own money to buy something, I’ll sell it. I make $3, $5 that way.

Kaibe, 24, Venezuela, arrived August 2023: When you don’t have a job, you feel like you’re stuck because to go out anywhere, you need $5. To get into the subway, you need $3. Even when people say, “Yes, come here; I have work,” then they send a location and I can’t get there.

Ibrahima, 24, Mauritania, arrived July 2023

Undocumented migrants are eligible only for Emergency Medicaid. Receiving this, of course, requires submitting a complicated application, then waiting months for approval. Coverage is limited to severe health issues that require immediate attention. Simple health issues can quickly become disastrous.

Ibrahima: I broke my leg, and I need to see a doctor, but since I don’t have my Medicaid card, it’s not easy to go to the hospital. I’m waiting for my Medicaid before I do any tests or get any pills. You can go to the hospital, but you have to pay for whatever they give you. So I’m still waiting to go. In December, I got a cold. The shelter called a doctor for me. She told me to take Tylenol, but I couldn’t afford it.

Bryan: When I first arrived, there was something wrong with my lungs — pneumonia, I think. I spent one night in the hospital in Queens. A couple of months later, I went to my first ID appointment, and they told me that I had debt I had to clear with the state: $10,000 of it. I’d had no idea. They told me I should have gotten some kind of insurance before I went to the hospital. But I didn’t know how. I went back to pick up my ID a few weeks later, and they told me it had gone up to $12,000 with interest.

Maiwand, 35, Afghanistan, arrived December 2023

Many migrants told us they wanted to go back home — their lives here are just too difficult. But even this has become impossible for many who have lost their passports. Appointments with national embassies, many of which have backlogs, are challenging to obtain. The Consulate General of Venezuela has closed entirely.

Luis: Everywhere you go, people look at you with fear. Like they see something ugly. I want to see my kids again. My son is 7, and my daughter is 4.

Wuilmer: In September, I heard my dad was sick. And I have two children and a grandson. I feel cheated, and I feel bad because of all of the things I’m experiencing now. I want them to deport me to Venezuela. But they won’t because I don’t have a passport. I need to go to the Mexican Embassy to see if they can solve my passport problem and get me deported.

Fernando: I am thinking of returning to my country. At least that country is mine. I had my whole life. Here, I am nobody. Here, I am the last wheel of the car. I am a person of basic general education. Being here in this situation is very uncomfortable for me because I’ve never experienced anything like this. I’m putting the effort in. But I am disappointed. My friends say, “You have gone through this, this, this, this, this, this, and you are already here, and now you want to go back?” They say, “No, no, no, no, no, don’t go.” I understand because it is hard to come here. But once you are here, it’s another struggle. Unfortunately, I lost my passport. I tried to make an appointment to return to my country, and they told me I couldn’t without it. Now, I’ve made the appointment, and they tell me I have to wait 40 days.

Bryan: A lot of people have been contacting me from back home, and I think, What do I tell you? The truth? I had everything. I had my house. I had my car. I wanted to be there. And we sold everything to come here for the American Dream. So I tell them, “If there’s one thing to know, it’s do not come here with the mentality that it won’t be hard here. It’s hard here. It’s very hard.”

Steven: I still communicate with relatives. I tell them not to come.

From left: Italo, 48, Venezuela, arrival date unknownJohn Wesly, 31, Haiti, arrived December 2023

From left: Italo, 48, Venezuela, arrival date unknownJohn Wesly, 31, Haiti, arrived December 2023

From left: Mamadou B., 36, Guinea, arrived November 2023Montelieu, 60, Haiti, arrival date unknown

From left: Mamadou B., 36, Guinea, arrived November 2023Montelieu, 60, Haiti, arrival date unknown

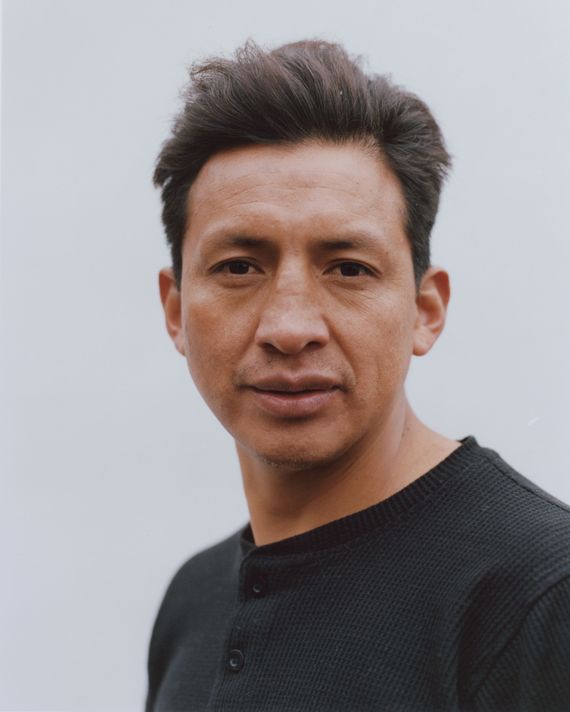

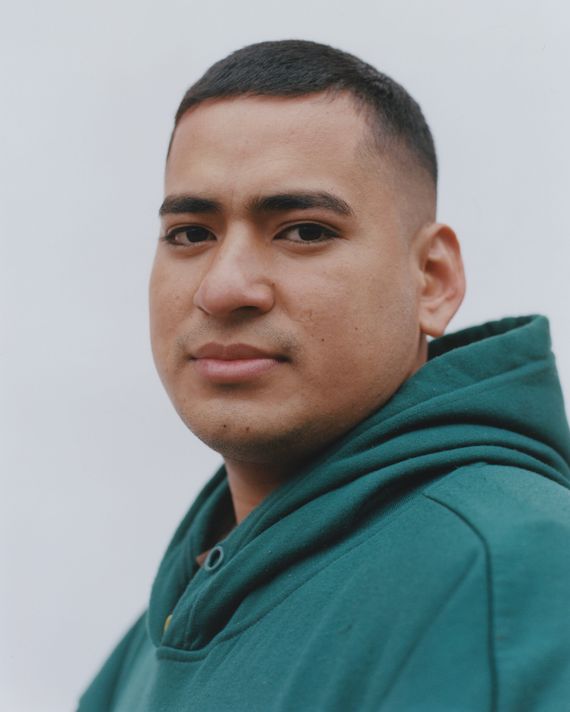

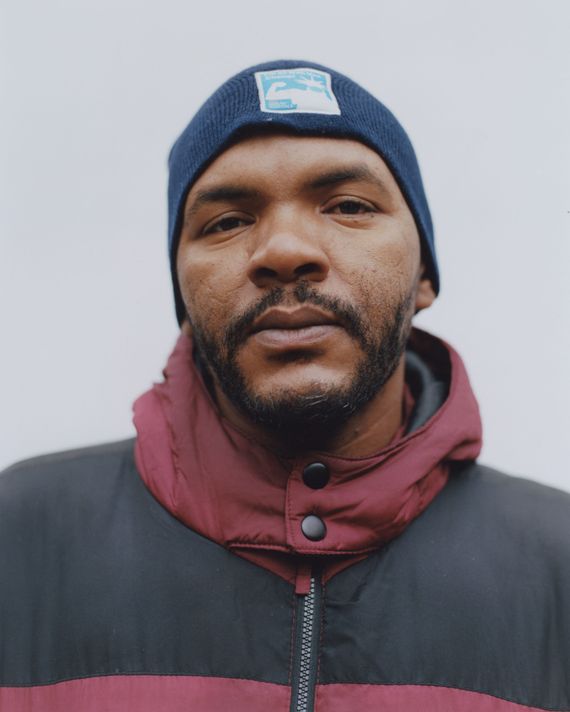

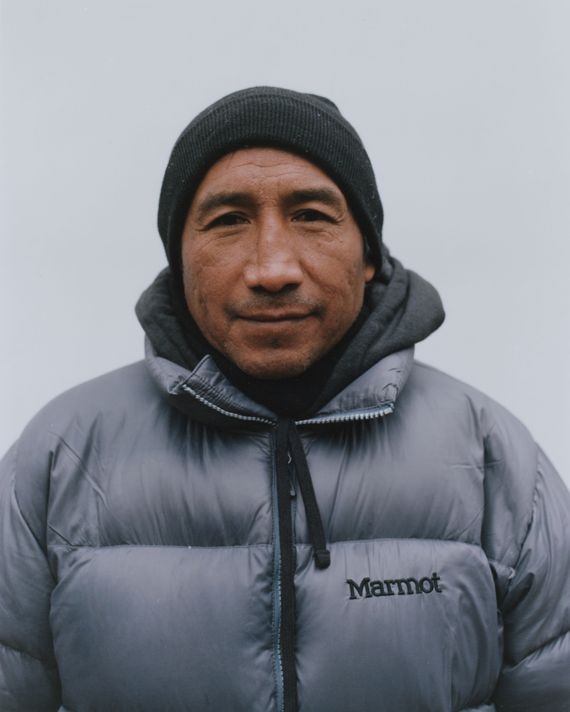

Portfolio by Philip-Daniel Ducasse. First photo grid: Top row, from left: Ibrahima D., 24, Guinea, arrived December 2023. Kaibe, 24, Venezuela, arrived August 2023. Mamadou H.D., 39, Guinea, arrived September 2023. Second row, from left: Aliou, 23, Mauritania, arrived August 2023. José, 56, Venezuela, arrived June 2023. Moussa, 33, Senegal, arrived August 2023. Third row, from left: Yonathan, 50, Venezuela, arrived November 2023. Enrique, 30, Ecuador, arrived April 2023. Mario, 25, Haiti, arrival date unknown.

Source link