The Rock Climbers and Stewards of Central Park’s Boulders

Kevin Reyes at Rat Rock.

Photo: Ali Cherkis

In some ways, Frederick Law Olmsted made Ashima Shiraishi a climber. She was 6 when she first tried to scale Rat Rock, a long, low outcropping of Manhattan schist in Central Park, just north of Columbus Circle. It was a very kid thing, to see a big rock and want to climb it, but having that kind of encounter while growing up in the Garment District was also something like a miracle of urban planning. “The fact that they decided to keep some of the bedrock exposed instead of blasting them was the reason I got into rock climbing,” Shiraishi, now 22, says of Olmsted and Calvert Vaux’s choice to incorporate some of the existing landscape into the park design. Shiraishi, whose quiet demeanor matches the balletic grace of her pulls, is widely considered one of the best climbers in the world. But she started out sending climbs in the park’s south end, and can still walk me through the first route she ever completed when we meet there on a cold February morning.

Kaci Collins Jordan climbing at Westside Outcrops. Photos: Ali Cherkis.

Kaci Collins Jordan climbing at Westside Outcrops. Photos: Ali Cherkis.

Rat Rock, which is also called Umpire Rock by people in denial about our rodent issues, is probably the most well-traveled outdoor-climbing area in New York City. But there are spots across the park — tucked away behind trees or behind a fence in the Ramble — that climbers have been frequenting for decades. (According to at least one climbing guide, an agreement between climbers and the Parks Department was made in the late 1980s to sanction the practice as long as they didn’t use rope.) When the city shut down in the early pandemic, even more people discovered it. “People got stir crazy and there was a boom in people trying to find new problems and new boulders,” says Kaci Collins Jordan, a teacher who has been climbing in Central Park for almost a decade. (She keeps a spreadsheet of every route she’s found in the city, mapping over 400 climbs, including spots in Van Cortlandt and Fort Tryon.) “It’s a bastion of a particular kind of climbing ethos,” Jordan says. Climbing gyms can be expensive. The park is free. “There are a lot of climbers of color, queer climbers, and trans climbers like myself.” While climbing and outdoor-sports culture in general has historically been dominated by white guys, Brittany Leavitt, who runs the nonprofit Brown Girls Climb said that outdoor climbing here in the city feels “vastly different.”

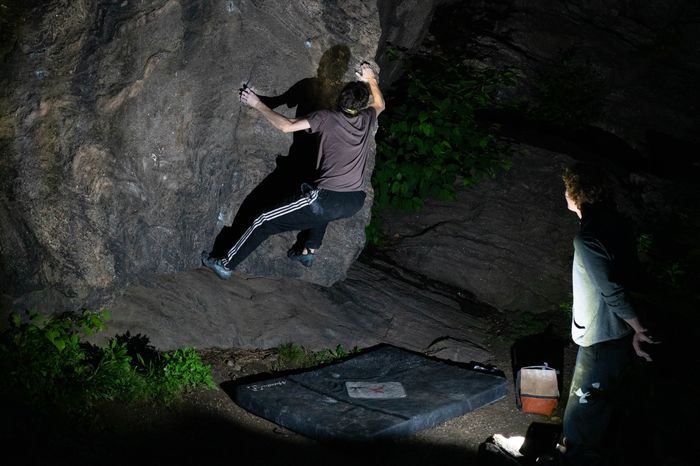

Left: Dane Kranjac climbs Cat Rock after the sun falls. Right: Schuyler Lewis watches Dane Kranjac climb during an early evening session at Rat Rock. Photos: Ali Cherkis.

Left: Dane Kranjac climbs Cat Rock after the sun falls. Right: Schuyler Lewis watches Dane Kranjac climb during an early evening session at Rat Rock. …

Left: Dane Kranjac climbs Cat Rock after the sun falls. Right: Schuyler Lewis watches Dane Kranjac climb during an early evening session at Rat Rock. Photos: Ali Cherkis.

The boulderers of Central Park have also become its unofficial stewards. When I visit Rat Rock, the ground is peppered with what looks like leftover confetti from a birthday party. There’s trash, such as discarded chip bags and at times needles and vials, to be attended to, but unlike other outdoor-climbing areas, which usually have organizations dedicated to caring for the boulders, climbers in the city do it ad hoc, often bringing trash bags with them. (Leavitt and others are in the process of trying to get a coalition together to change that.) Marc Adrian, a climber who works at a gym in Gowanus, says that at the beginning of the season, he and his friends will bring brushes and clean the rocks of “all the gunk” — dirt, snow, leaves — that accumulates. “When some people have free time during their week, they just show up and if it’s unkempt they’ll try to organize it,” Adrian says. “It’s kind of an unspoken rule in general.”

Ashima Shiraishi at Rat Rock. Photos: Ali Cherkis.

Ashima Shiraishi at Rat Rock. Photos: Ali Cherkis.

In many ways, the park is a more democratic space to climb than the city’s indoor gyms — now increasingly part of well-financed chains like Movement or Vital. But in practice, it’s a little more complicated. Jordan sees the park as a place of recreation, but also of need, which can sometimes get lost among climbers. (Instructions for reaching Cat Rock on Mountain Project read: “Take the path from the stairs to avoid stepping in dog and homeless-man shit.”) “I’d love to see the climbing community advocating for folks who are using these spaces because they have to.” Leavitt agrees, pointing out the contradictory history of the park itself, which was founded on a principle of access but also displaced more than a thousand people, including Black residents of Seneca Village. As we sit basking in the sun in between climbs, she tells me how she’s found bouldering as a way to reconnect with that history. “I think there’s that beautiful fine line of it.”

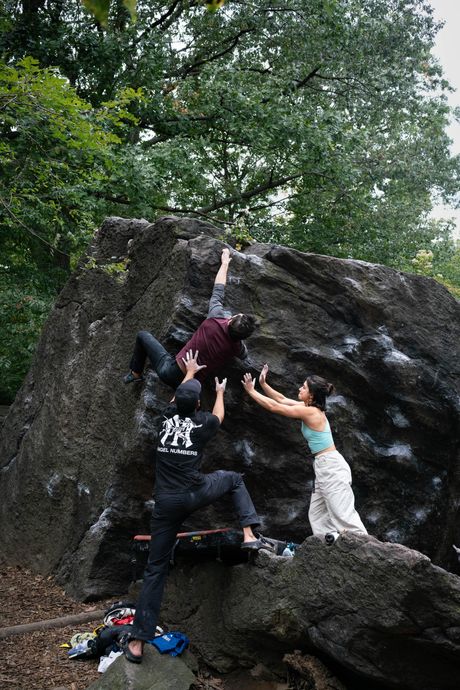

Jesse Friedman (L) and Marc Adrian (R) spot Luna Adler at Worthless Boulder.Marc Adrian and Luna Adler spot Jesse Friedman at Worthless Boulder.Photos: Ali Cherkis.

Jesse Friedman (L) and Marc Adrian (R) spot Luna Adler at Worthless Boulder.Marc Adrian and Luna Adler spot Jesse Friedman at Worthless Boulder.Photos…

Jesse Friedman (L) and Marc Adrian (R) spot Luna Adler at Worthless Boulder.Marc Adrian and Luna Adler spot Jesse Friedman at Worthless Boulder.Photos: Ali Cherkis.

It’s impossible not to feel the park’s history when climbing there. And maybe it’s because of this that climbers speak with a kind of reverence in the presence of the rocks, even though they’re not all world-class climbs. (Some — climbers argue, though — are.) The Manhattan schist of Rat Rock is the same bedrock that holds up the city’s skyscrapers and cradles its subways. “It’s a way to interact with something really ancient about this place and it feels special,” Shiraishi says. The grooves that are now smudged with climbing chalk are scars from the last Ice Age, carved by a glacier that also dropped the boulders throughout the park. As we watch the flecks of mica catch the mid-afternoon light, Shiraishi runs her hand over the holds. “It almost feels like our fingerprints are just one guest out of so many,” she says.

Kayra Viezcas climbing in the Ramble. Photos: Ali Cherkis.

Kayra Viezcas climbing in the Ramble. Photos: Ali Cherkis.

Source link