What People in Los Angeles Grabbed or Lost to Wildfires

On her way out the door of her home in Santa Monica last week, Melissa Rivers took a drawing by her mother, Joan Rivers. “It’s amazing what you grab,” Melissa Rivers told a reporter on CNN. “I know I can find the photos. But a drawing of hers I can’t replace.” The novelist Colm Tóibín delivered the news that the personal library of Gary Indiana had been lost to the fires in Altadena in an essay that also described his own decision-making as he evacuated Los Angeles. He grabbed, of all things, a briefcase and a freebie tote from the Charleston Literary Festival — as if he “would, for the little that is left of my life, always regret that I had not taken this briefcase and tote bag.”

The calculus in such a situation can seem absurd, even to the people experiencing it in real time. “I was stressed about choosing because it would not have mattered which thing I took, in a way,” says the podcast producer Myka Kielbon, who evacuated an apartment in Glassell Park. “Instead, if I lost my home, that object would matter because it would be the only thing I have left.”

Curbed asked a dozen people who fled their homes in the wildfires about the objects they lost and what they saved.

Peterson’s art that survived (left) and his daughter Coco Peterson’s work that did not (right). Cleon Peterson; Coco Peterson (@cocopetersonart) .

Peterson’s art that survived (left) and his daughter Coco Peterson’s work that did not (right). Cleon Peterson; Coco Peterson (@cocopetersonart) .

“We’re right by Eaton Canyon, and on the right side of our house was basically a wall of flame. I didn’t even grab a piece of my own art. My wife grabbed a car and the dog and my computer.

“When my friends are reaching out to ask if I’m okay, I think about the piece of art they gave me, like a painting by Adam Beris, or art I was storing for Mark Lanegan, who died in 2022.

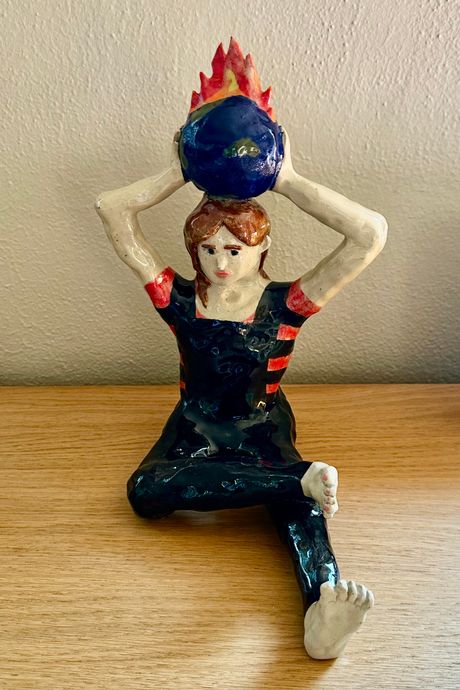

“There’s one ceramic piece, by my daughter — my wife and I are super sad that we lost that. It’s an image of her as a 12-year-old holding a globe with the world on fire on top of her head. And it’s her in her overalls with her striped shirt on and brown hair. It’s an interpretation of an image I made after the fires in Malibu. She was becoming this awesome artist, interpreting the world through her art just like I do. To me it was an image of uncontrollable powerlessness — that feeling you know everyone shares, but through a kid’s eyes. My daughter’s sculpture was a symbol of someone becoming who they are in a moment of time we’ll never get back to.”

Photo: Daniella Pineda

“The night of the fire my door was banging and my neighbor is there, warning me to get out, and I see this fireball ahead. I took ten seconds and grabbed my dog, my passport, my Social Security card, and my laptop.

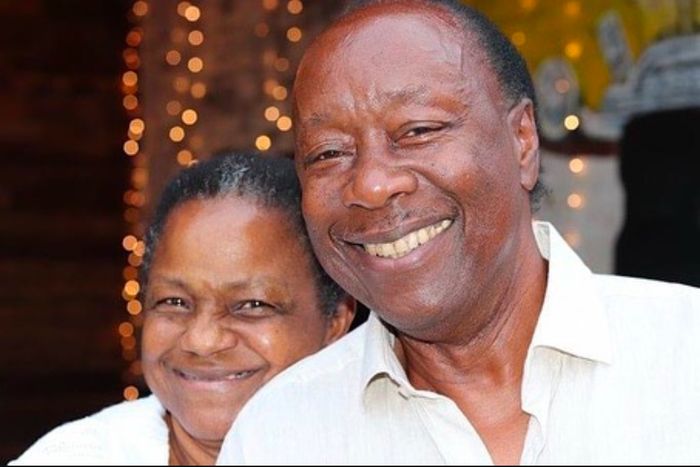

“I lost all my baby pictures in a house fire when I was maybe 3 years old, and this fire took the rest. There was a picture of me and my aunt Celeste in a pink sweater smiling, sitting at a table, and she’s holding me on her lap and her hand is on my belly. I’m a toddler wearing these little blue overalls and a long-sleeve little shirt, and my cousin Leah is also in the picture and we’re all smiling and looking at the camera. I had a pretty complicated upbringing — very unstable — and I lived with a lot of different family. But Celeste was my first mother. I wish I had taken that picture.”

Jones on the red carpet of the Oscars the night he performed in a watch that became a treasured object.

Photo: Momodu Mansaray/Getty Images

Derrick T. Jones, who performs as DJ D-Nice, was fortunate that his house survived the fires after he evacuated. On his way out the door, he grabbed the essentials — and a watch.

“The watch was initially a loaner — I was DJ-ing the Oscars. I later asked the watch-maker if I could purchase it so I could etch the Oscars date on the back, with the hope of gifting it to one of my kids someday. How many DJs can say they played at the Oscars? It was a highlight of my career, and I wanted that keepsake to remain in my family.”

“We were in that house a long time, 37 years. Last night, my 6-year-old granddaughter was asking me whether it was a big deal if you lost a house. It made me think. I had a box of all the things I collected from my life when I was a kid until now, arranged chronologically. There were things I made when I was 2 or 3 years old and stuff my mother made, like a book about how much I weighed and what presents we got from people. Then there were certificates and diplomas, or newspaper articles about me, all through my life.

“And who cares. It didn’t make any difference except I thought my daughter and son would want to look through it once before throwing it away. I had also saved a bunch of stuff my daughter and son gave to me when they were kids for the same reason. My 6-year-old granddaughter had already started to look at it. She was fascinated by it because there was stuff from her mother — my daughter. I would have taken that.”

The portrait of Morris’s grandmother hangs above a lamp.

Photo: Victoria Morris

“I lost my house and my business — both. I had a beautiful pottery studio and showroom. I dedicated my life to it. We left with next to nothing. My life history feels erased.

“I’m a fourth- or fifth-generation Californian. My mother’s side has been here since the 1800s, so I had a lot of family heirlooms. But one of the biggest losses is the drawing of my grandmother by my great-grandfather Paul Swan. He was a portrait painter and sculptor and kind of famous in his lifetime. He was gay, but he had an early marriage. Distant relatives, they gave us this portrait of my grandmother.

“To me it’s just such a deep, sweet thing. My grandmother was a really special person and to have a beautiful portrait of her when she was young was like having her in my house. She represents this kind of spiritual-safety person for me, this person who I kind of thought was watching over me.”

From left: Photo: Seanay SingletonPhoto: Seanay Singleton

From top: Photo: Seanay SingletonPhoto: Seanay Singleton

“My grandparents are 82 and 78, and they had lived in that house for 55 years. They were woken up out of their sleep by a loudspeaker on a police squad car, calling on people to evacuate. They were able to get out with the clothes they were wearing and identification.

“It was a house that was lived in and full of life. What I’ll miss, honestly, is the photos — all the family photos that lined the hallway walls. And in my grandmother’s room, there’s a picture of my grandfather’s mother with them as children. The way things were burned up, there really was nothing left. Even the metal filing cabinets that were fireproof were all dented and everything inside of them burned.”

“I edit from home and it’s where I made Last Flight Home. It’s about my family, so I had 500 hours of filming of my family and my dad, and all the scrapbook and archival footage that you can’t replace. And I had footage of my son from birth to age 21. I was going to make a film about him. And I had a huge crate of journals, so heavy it was hard to carry, from age 5 to age 52. I’d been thinking about making a film about what it’s like to live behind a camera using the stories in journals and the footage of our family. It’s like the end — a death of a kind. It’s sort of a tabula rasa, an exercise in acceptance.”

“My version of Ondi’s journals is my rehearsal recordings. I lost all my rehearsals from the first bands I played in and all the music I ever developed, especially early first four track recordings. I’m 55 now, and those would have been from when I was 19 or 20. I’m also thinking of my Nyckelharpa, a Swedish stringed instrument sometimes called a keyed violin. They’re hard to find and I’ve used it on every film score recently — maybe six films. And if you do find one, it won’t have the same tone.”

Photo: Alex Zaragoza

“We’re renters, but our house is filled with everything we own in the world. It was wild going around with an empty suitcase. I took photos, family heirlooms, jewelry, then I had a moment of going through my closet really fast, like if you’re flipping through record sleeves. I was asking: What matters to me? What matters to me? What matters to me? Like, How many crop tops am I going to need if everything else in my life falls apart?

“When I started writing TV, I was like, Oh, this is what money is like. And I bought myself a denim jacket from A.P.C. — a really nice denim work jacket. Never in my life would I have bought a $400 jacket before, and I took that.”

From left: Art: Jaime Cortez; Photo: Beatriz CortezArt: Jaime Cortez; Photo: Beatriz Cortez

From top: Art: Jaime Cortez; Photo: Beatriz CortezArt: Jaime Cortez; Photo: Beatriz Cortez

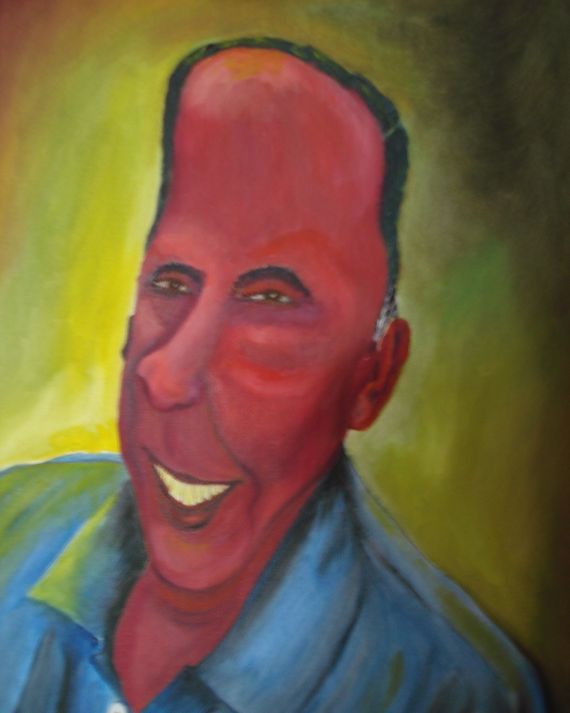

“When the fires began, it was Tuesday night and I was still in Davis, where I teach, so I wasn’t able to go back to my place to take everything out. I am sad about losing the two paintings by my father. He didn’t make a career as an artist but he is an artist. It was great to be surrounded by another artist all my life and their work. One was of vegetables — red bell peppers that were huge. The other one was a self-portrait as a ‘grape man.’ His face was purple and enlarged.

“Every once in a while, I remember something I lost — my favorite shirt or my favorite boots. Those things can be replaced. My dad is 85 now, and I don’t know if he could make those paintings now.”

Stacks of MUJI notebooks on a bed where Kielbon has been staying.

Photo: Myka Kielbon

“Looking around, I was like, What matters? I felt like I couldn’t pick a single thing, but there’s one shelf that’s entirely journals, 30 to 40 of them. I’ve journaled for ten years. I’m a pretty good memory keeper for my friends and community. I do reread them a lot. I put all of them in a grocery bag.

“Once I was in the car, I realized that I was stressed about choosing because it would not have mattered which thing I took, in a way. Instead, if I lost my home, that object would matter because it would be the only thing I have left.”

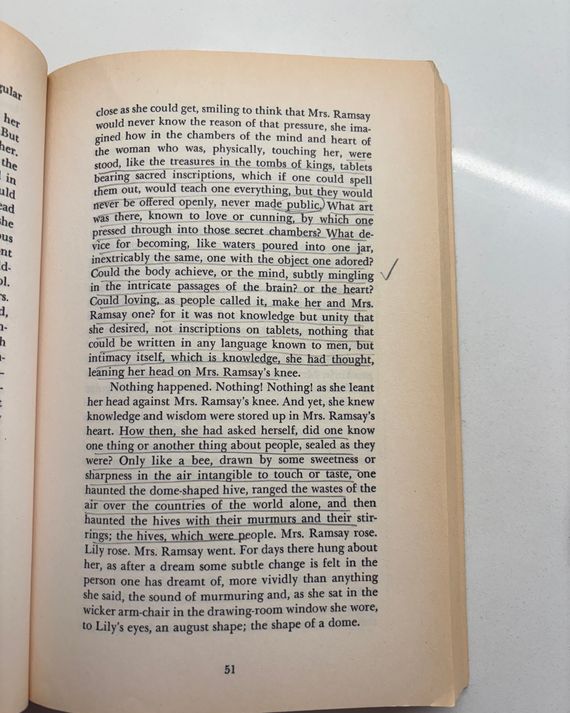

Photo: Logan Lockner

“It sounds like a joke, but it’s true — I took my copy of Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse. I remember reading this for the first time the summer after I graduated high school. I read it at the beach, not even intentionally. It was a big thing to me. I read it a few times throughout college. Yes, I could just get another copy of the book, but it’s not going to have my notes and marginalia and these layers. And losing that artifact would feel like losing touch with that history or tangible evidence of it.”

These interviews were condensed and edited for clarity.