When NIMBYs First Got Their Veto Power

Photo-Illustration: Curbed; Photo: Getty

Here come the housing wars again. Governor Kathy Hochul recently struck a budget deal with leaders in the state legislature that includes a program to boost residential construction. At the same time, Mayor Eric Adams is pushing his “City of Yes” plan, loaded with zoning tweaks meant to sprinkle new construction around all five boroughs. Even before anyone had a chance to analyze the specific measures, anti-density artillery was being rolled out to shoot down both proposals, or at least riddle them with exceptions. Months ago, the Adams proposal was already taking heat at public hearings in Brooklyn. The organization Equality for Flatbush warned in an Instagram post that “Rezonings ARE ALWAYS about corporate greed, gentrification and the displacement of New Yorkers. @nycplanning [the Department of City Planning’s] sole purpose is to gentrify #NYC.” More recently, Paul Graziano, a Queens-based urban-planning consultant, has been trying to mobilize Queens with a presentation aimed at killing both state and local proposals. It’s titled “City of Yes and Housing Opportunity: How These Two Packages Are an Extinction Event for Our Communities in Queens and Beyond.” On this issue, Gen-Z Black Lives Matter activists and middle-aged mortgage holders who live in single-family homes stand shoulder to shoulder.

And yet everyone knows that New York needs more apartments: affordable, market rate, small, big, cheap, luxurious — whatever. Just more. And many New Yorkers would love to see new housing get built, so long as it’s the right kind in the right place, which is to say somewhere they don’t have to look at it — somewhere new residents won’t compete for their parking spaces, jam their subways, overload their sewers, or threaten the precious character of their neighborhoods. Suburbanites and conservatives have long been candid about why they oppose greater density in quiet residential areas: It brings the wrong kind of (poor) people, disturbs the local (racial) equilibrium, and depresses property values. Anti-gentrification progressives oppose new development in cities for reasons that are both similar and opposite: It brings the wrong kind of (rich) people, disturbs the local (racial) equilibrium, and boosts property values. The upshot is a severe housing shortage that has spread out from grotesquely distorted markets like New York, Boston, and San Francisco to hit smaller cities and heartland towns.

In a persuasive new article published by Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies, the urban historian Jacob Anbinder traces that strange consensus, and the crisis it birthed, to a shift in liberal New York politics in the late 1960s. As the city suffered and the middle class fled, many urban liberals blamed the previous generations’ top down, blunt-instrument housing policies. The strategies of mass demolition, urban renewal, public housing, and highway construction had done nearly as much damage to American cities as American bombers had to the physical structure of German cities during World War II. The New Leftists felt that the only way to reverse the raze-it-all approach to urbanism was to smash the pols’ monopoly on control and scatter it to ordinary people who knew what their block needed and what was worth protecting. Norman Mailer conducted a rabble-rousing campaign for mayor on the slogan “Power to the Neighborhoods!” He hoped to unseat the more even-keeled Establishment figure John Lindsay, who floated a similar idea of peppering the metropolis with “little city halls.” That kind of talk emboldened residents of Forest Hills to fight the big City Hall and try to block Lindsay’s plan for a new public-housing project there. None of those warriors got much traction. Mailer got creamed in the election. Lindsay could barely hold on in a city that was spinning out of control, and Forest Hills had to swallow the new project.

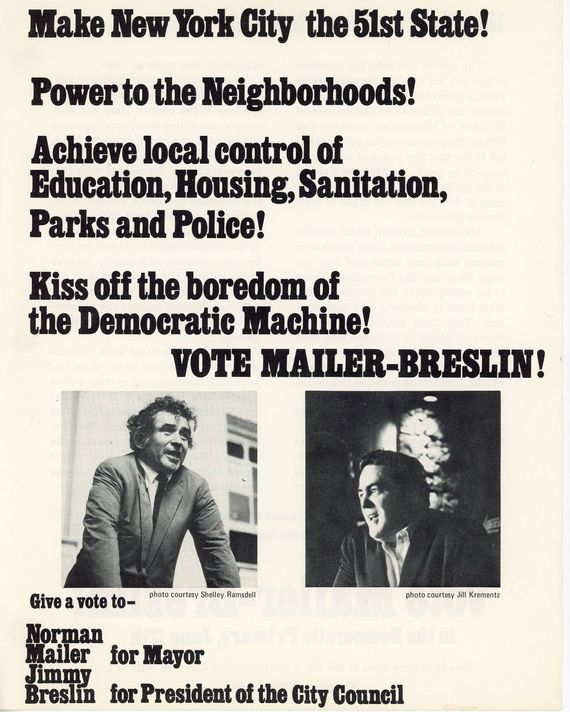

The 1968 campaign flier for Norman Mailer’s mayoral campaign with running mate Jimmy Breslin on a neighborhood-empowerment platform.

Still, the idea of giving ordinary New Yorkers a louder voice in local affairs proved popular and enduring, and it eventually embedded itself in the institutions of governance. It also established a standard, more or less democratic procedure to approve zoning changes and variances: the Uniform Land Use Review Process. ULURP (pronounced You-lerp by those in the know) codified neighborhood consultation as part of the development process. A revised city charter in 1975 gave community boards, made up of part-time appointees, an explicit role in deciding what, how, and where to build. Consequently, developers who need some concession from the city on a new project — a taller tower, say, or an affordable-housing subsidy — begin by trying to win over the community board, or, in Anbinder’s terminology, a “handful of unelected neighborhood notables.” Well-run community boards perform plenty of crucial tasks, mediating between the municipal technocracy and locals’ deeper understanding of the urban terroir. But one of their principal tasks remains to challenge plans, balk at development, and demand more public benefits, a process that inevitably slows the pace of new housing and raises its costs. Anbinder argues that the movement he calls the New Neighborhoodism amounted to handing out vetoes over new construction of all kinds with predictable results. He quotes an aide to Mayor Ed Koch complaining about the politics of resistance in 1982: “Sanitation garages, methadone centers, halfway houses. You name it. People don’t want it.” That attitude effectively meant prioritizing the protective urges of each small enclave over citywide needs — with results that have become clear half a century later. “The restrictions on urban development that marked the era of neighborhood liberalism set the stage for the severe housing shortages that New York and similar cities would experience in the twenty-first century,” Anbinder writes. If you can’t find an apartment under $4,000 a month today, you have Mailer, Lindsay, and the Forest Hills protesters to thank. The Adams administration’s plan consists mostly of a package of common-sense rule changes that have been adopted in other parts of the country without causing skies to fall. It allows small apartment buildings near transit stops, gets rid of requirements to build unnecessary parking structures, and makes it easier to convert fallow office towers into residential buildings. But the details don’t matter much when you’re primed to say no.

Anbinder sees opposition to new housing as an ideology, the kind that cherry-picks justifications, tunes out discordant data, and cultivates dramatic rhetoric. (Stop the bulldozers!) It anoints an enemy — developers, in this case — and endows them with powers amplified by collusion with elected officials. It’s a philosophy of rejection, specific in its aims and adaptable in its rationales. “In order for an ideology to be widely embraced by diverse groups of people, you need to provide multiple entry points,” Anbinder says. “For leftists, that’s community self-determination. For a white-collar aestheticist, it’s historic preservation.”

Of course, YIMBYism is an ideology, too, predicated on the proposition that density is a self-evident good. Cities, the argument goes, should provide shelter to as many people as possible on the smallest possible expanse of land. (Ideal density would liberate acreage from sprawl and return it to nature.) That imperative must preempt any special pleading or sentimental allegiance to the way things used to be. Both philosophies have their fundamentalist extremes, but NIMBYism has been more sweepingly influential for decades. That’s partly, Anbinder suggests, because it offers a more straightforward narrative and a clearer path to success. “Anti-growthers draw a visceral connection between what’s happening around them and social issues,” he says: New and bigger buildings breed crime and drugs, for instance; or new and bigger buildings will force you out of your home. “YIMBYs haven’t figured out how to do that as well. The reality of how to fix the housing crisis is complicated. You might argue that you’ve successfully cut the rate of price growth from 10 percent to 5 percent, say, but it’s hard to sell that as a victory.”

In the long run, the Power to the Neighborhoods! program produced the opposite of its ambitions: a city that is less affordable, less democratic, and less nimble — a city where a 23-year-old married ex-GI with literary ambitions would never find his first walk-up apartment in Brooklyn Heights, as Mailer did. “The antigrowth revolt was a very understandable reaction to a very dire situation” in the ’60s and ’70s, Anbinder says. “It’s a story of people who were bold enough to see changes that needed to be made and made them. But it’s also a tragic story of how those well-intentioned changes sowed the seeds of the housing crisis. Those reactions were understandable in their time. Today, we face a new set of challenges.”

See All